The Monster of Invidia, by M L Hufkie

“I’m very sorry sir. We did all we could.”

He didn’t hear much other than sorry and could. Two inescapable words that only ever sought to remind us of what cannot be undone and distant possibilities. He saw the doctor’s mouth move and felt nauseous at the smell of disinfectant emanating off him. Or maybe it wasn’t him. Maybe it was the walls, the floors, the air. Two words that have hovered and continue to hover over his family for the last six years. At least him and his wife.

“We will keep her for a day or two. She’s lost a lot of blood and we want to make sure she doesn’t haemorrhage. Again, I am terribly sorry. If…”

He got up and started walking away from the doctor, leaving those words to follow him down the empty hallway.

The hospital looked deserted, though he knew it wasn’t. It was just that floor. Silent, and dank, like a sepulchre. He had been seated on an uncomfortable metal chair outside the room that an hour ago his wife had been pushed into – a long, bitter hour that had a nocturnal stillness wrapped around it even though it was broad daylight. When he rushed through the doors with his wife sweaty, and panicking in his arms, there had been mayhem at the entrance. A bus accident on the N1 between Milnerton and Cape Town. Casualties yet unknown. Passengers, 59. Extent of injuries-anything from broken ribs, arms, a cracked skull, broken toes to an impaled body so badly damaged that the doctors and police were still trying to identify it. Blood everywhere. Screams and panic as doctors and nurses scurried around to comfort, inject, bandage-up, sooth, and alas push the more serious cases off down long corridors to invisible rooms from which they may never return.

He reached the exit downstairs and collided with a woman who appeared intoxicated. Covered in blood with one shoe missing and a torn dress she grabbed him by the chest, ripping a button off his shirt in the process, and mumbling incessantly about her son.

“Where is my boy? He is 7. Has anyone seen my boy? He was right next to me on the bus. Please…”

The anguish in the woman’s eyes brought tears to his own and he swallowed hard. Two orderlies in crumpled overalls appeared out of nowhere, one of them pushing a wheelchair.

“Sorry, sir. She came in with the bus people. They sedated her, but she must have wandered off.”

He nodded and walked to his car where he broke down slamming the roof, looking through tear-filled eyes at the grey façade of the hospital.

The fourth miscarriage. Eight years and four dead foetuses. After the third he had sat his wife down, talking to her earnestly. A very difficult conversation in which he felt like he was crushing her, taking her dream from her.

“My angel, perhaps we ought to stop for a while. Give your body time to fully regain its strength. We could-

“Could what!? I’m 35 years old. I am running out of time.”

This is not a fucking race! This is your life! This is my life!

He was relieved to find that he’d only thought the words biting his tongue as his wife broke down sobbing in his arms.

With each new pregnancy, it was as if they were being taunted. Each failed pregnancy lasting slightly longer than the previous one. Just enough for them to foolishly hope. The first was roughly a year and a half after their wedding. He couldn’t take his eyes off his wife, so radiant and beautiful he found her. It lasted seven weeks. Until she woke up one Saturday morning, blood oozing from between her legs, staining the summer nightdress she’d been wearing, calling his name. Preparing breakfast, he’d run from the kitchen and knew that the baby was gone before the doctor told them. The second, a few months later, lasted nine weeks before meeting the same fate as the first. The third lasted twelve weeks. He had made sure his wife was always comfortable, got domestic help to cook and clean so she could rest, and during those weeks the ghost of the previous two was slowly fading. In the evenings he would find her reading or watching TV, content and relaxed. The two of them discussing names, talking about what he or she might be like, his wife buying tiny pieces of clothing that made his chest hurt whenever she showed him a new item she had procured. And then one night, soaking in the bathtub while he was listening to music, a desperate, heart wrenching scream like that of a wounded animal. He would never forget the red of the water, the fear in her eyes, his own disbelief when he’d picked her from the tub, wrapped her in a blanket and driven her to the hospital.

And now here they were again. At a different hospital for the same thing. They had been taking an afternoon stroll by the Sea Point Promenade. The sun high, the breeze carrying that wonderful green, salty scent of Cape Town. The place was packed with runners, surfers, swimmers, and hand-holding couples. They had just sat down at a restaurant for an early dinner when her cramps started. Fierce and constant. The baby came out in pieces. In the hallway of yet another hospital he could hear his wife moan and cry, and when his own tears came, he didn’t try to stop them.

How long he sat in his car he couldn’t say, but he pulled out of the hospital car park when the noise of an approaching ambulance interrupted his thoughts. He somehow ended up on the Sea Point Promenade again, sitting on the bench they had sat on so many times before. By the time the sun set, painting the Cape Town sky a marvellous orange-yellow-purple, he had made his decision.

When he got back to the flat, the silence of it made him uncomfortable. It was cloaked in the type of quiet that spoke of the coldness of uninhabited rooms and echoed footsteps. For a wild moment he thought about driving to his parents but abandoned the idea almost immediately. Twice he picked up the phone in the kitchen, dialling their number only to replace it before anyone could answer. He showered and poured a whiskey. Sleep took hours to come, and when it did, he had nightmares about their nameless, half-formed offspring floating beneath the city; down in the sewer amongst plastic, shit, used condoms, discarded needles and other things that have lost their shape; choked by debris, their mere slits of mouths singing a disjointed chorus:

“Help us, Daddy. Daddy, please help us.”

A murderous headache roused him at the crack of dawn and after taking a shower he packed a bag for his wife and left for the hospital. It was too early, so he drove along Chapman’s Peak to Simons Town, forced himself to have breakfast at the first café he saw and then continued from there to Fish Hoek where he aimlessly browsed a few shops.

He didn’t want to try anymore. Didn’t want her to try anymore. He didn’t want to feel her desperation every time they made love. Didn’t want her clinging to him, her legs around his waist, gripping whispering “please, please my love -” tormented by the need for him to fertilize her. When he arrived at the hospital, he was taken to a hall where his sleeping wife was lying on one of ten beds. He kissed her softly on the forehead, sighing with relief. As long as her eyes were closed, he didn’t have to see the pain in them, if her mouth was quiet, he didn’t have to listen to the confusion, anger, and heartbreak. The doctor entered quietly, a white-clad spectre.

“We’ve given her a strong sleeping draught. She’ll be out for a few more hours and should be good to return home tomorrow.”

“Doctor, do you think-“

“Yes, I think so. But I also think it wise for your wife to stop trying for a little while. The medical sciences have advanced greatly in the last 50 years.”

The doctor walked away before he could contest his theory. Frankly, he was sick and tired of being told about the great advances of medical science. A science that manages to transplant organs but one that still failed to save cancer patients who died in their millions across the globe. He frowned irritably, kissed his wife again and left. He drove to the bench, staring at scavenging seagulls while playing with his wedding ring as the day bled out.

She didn’t talk much on the drive home the following day, and he knew that he would have to wait until she felt ready. And so, he waited. After that, his wife changed. Her inability to have her own child made her avoid others with children. She stopped talking to her friends, and if she did mention them, it was only to point out their shortcomings as parents.

“Did you see what she gave her child to eat? And that idiot husband of hers is going to turn his son into an emotionally stunted macho dimwit like himself.”

Her criticism reached extremes and though she never said as much to the people she was grilling, he hated having to listen to it. His wife had always been a woman with a clear sense of justice, something she’d inherited from her political activist parents, thus though he didn’t like her sharp criticism he could forgive her for it. What started bothering him was that after the last miscarriage she began retreating from everyone, including himself. One of the things that first drew him to her was her passion. Not just in bed, but her passion for life, her passion for social justice, the amount of passion she poured into everything she did. There was none of that after the loss of the fourth would-be child. She became morose and taciturn, would stiffen up when he attempted to touch her.

About three weeks after her return from the hospital he came home to find her on the floor in the nursery, cutting into tiny pieces all the clothes she’d collected for a child that never came. When she saw him, she looked at him dried-eyed, ignored him and continued her destruction. One night after they returned from a nearby restaurant after a strained dinner, he woke up in the small hours to find her sitting on the edge of the bed. At first, he thought he was dreaming but then he heard her speak.

“Anything. I would do anything. I…would…please-“

He switched on the bedside lamp, and she turned to him looking utterly dazed and entranced.

“Darling, who are you talking to? Are you alright?”

And then she started screaming, a deafening wail that reverberated off the walls in their bedroom. Their flat was located on a newly upgraded block with security and a concierge, and he knew that someone would have heard it. He took her in his arms, covering her mouth, her eyes bulging with tears streaming from them. And then, without warning she bit into his fingers hard, until he pulled his hand away cursing.

“Ouch Fuck! Darling, stop it! Don’t…

Before he could finish his sentence, she fell backwards onto the bed, her lips stained with his blood, into a deep sleep from which she arose the following afternoon. Having taken the day off work, he waited patiently for her to wake up so he could try to find out what the hell had happened the night before. But when he asked her about it, she had no memory of any of it. No matter how he approached the subject, showing her his bitten fingers, taking her back step by step, she shook her head in confusion and tearfully apologised.

He left angry and confused driving to his parents’ house in Tamboerskloof. When he got there, he found he could not talk about it and simply said that she was fine when his father politely asked about her. His wife was an orphan. Her anti-apartheid activist parents were both murdered in the early 80’s. Her mother gunned down in an alleyway after a protest rally in Johannesburg, and her father blown to pieces by letter bomb while exiled in Angola.

“Karl, are you listening son?”

Solo visits to his parents had to suffice as they had never forgiven him for marrying her and their ambivalence towards his wife always led to ferocious arguments. He didn’t stay long, getting agitated by his father’s nagging about his joining the family law firm and his mother’s subtle digs at his wife’s charity work with orphans.

On the drive home he thought he would suggest a holiday to his wife. Away from the city, familiarity, away from their losses. They had both always wanted to return to Greece where they’d spent their honeymoon and they had the money to do it. He stopped by the supermarket to pick up some wine and fresh meat from the butchers with the idea that he would cook and talk to her about it. When he got home, he could immediately tell he was alone. He could always tell; the stillness was different. What surprised him was that his wife hadn’t left the house alone in weeks, and he got an acute sense of foreboding as he entered the rooms. The fact that it was early evening and still light out didn’t quell his worries, and he called her phone a few times, only to be informed by a tin voice that she wasn’t available.

He turned on the 6 o’clock news and poured himself a whiskey. The news only darkened his mood further.

In Cape Town, reports of missing children; a desperate, abused wife lacing her husband’s favourite stew with rat poison; a prominent Cape Flats gang leader murdered by a vigilante group, who shot him, threw a petrol bomb at him, and filmed him burning alive. North of Johannesburg; the dismembered corpses of at least a dozen black men unearthed on an abandoned farm. The property belonged to a white supremacist on trial for murder. When asked about the bodies on his farm he’d apparently smiled and replied to the journalist, “Blacks aren’t people.” And then in an absurd attempt to perhaps lift the spirits of a depressed nation, news of a Sandton based plastic surgeon believed to have discovered the fountain of youth. An elixir guaranteed to turn back the clock for the rich and famous. A potion he was now looking to sell to the highest bidder- a Californian pharmaceutical giant.

An hour passed and he called again. Nothing. He muted the television and leaned back on the couch. On the screen a young pop star was on some talk show doing the xibelani, much to the delight of the audience. He fell asleep and woke up to find his wife standing at the kitchen counter chopping a cucumber while sipping red wine. The steak he bought was next to her on a plate seasoned and ready to be cooked. When she noticed him looking at her from the doorway, she smiled at him for the first time in weeks.

“Where have you been? I was worried.”

“I am sorry. I just realised my phone was dead, I was going to call you. I went to see Sanita. There was a problem at the orphanage.”

Sanita was her social worker partner who ran the orphanage with her. The two women had known each other since university and had worked together for 8 years. Tomatoes and lettuce were taken from the fridge, and she spoke as she washed them.

“One of the new, younger boys attacked one of the older ones and ended up with some serious bruises, so I took him to the hospital.” He was elated. For weeks he was worried that she would lose her interest in her work, the way she’d lost it in everything else.

“What happened? Is the boy, ok?”

She nodded reassuringly, her brown eyes sparkling.

“I think he will be. We will all be.”

He took her into his arms, holding her to his chest and his joy grew when she didn’t pull away from him. Instead, she kissed his mouth, his neck and leaned into him as his hands wandered down her back. But something bothered him. It was her smell. She didn’t have her usual, crisp, citrus, scent that he so enjoyed inhaling. She smelled of decay, rotten meat, mingled with a horrible chemical smoke.

“Darling, you smell like-“

“Yes, I know. I am sorry.”

She turned away from him to the stove and stirred chopped mushrooms that had started frying.

“I couldn’t find parking close to the hospital and I ended up passing by one of those abandoned factories on Protea Boulevard. The place used to be an abattoir and is now filled to the rafters with meth junkies.”

“The slaughter factory?! Sweetheart, please avoid that place. It gives me the creeps. After all this time it still reeks of blood and dead animals. Did they bother you?” Her back seemed to stiffen very slightly, but she kept stirring and washing his whiskey glass he helped himself to some wine instead.

“The junkies you mean. Well, a few of them approached us, but they were not doing any harm. They just wanted money, and after I gave them some, they left.”

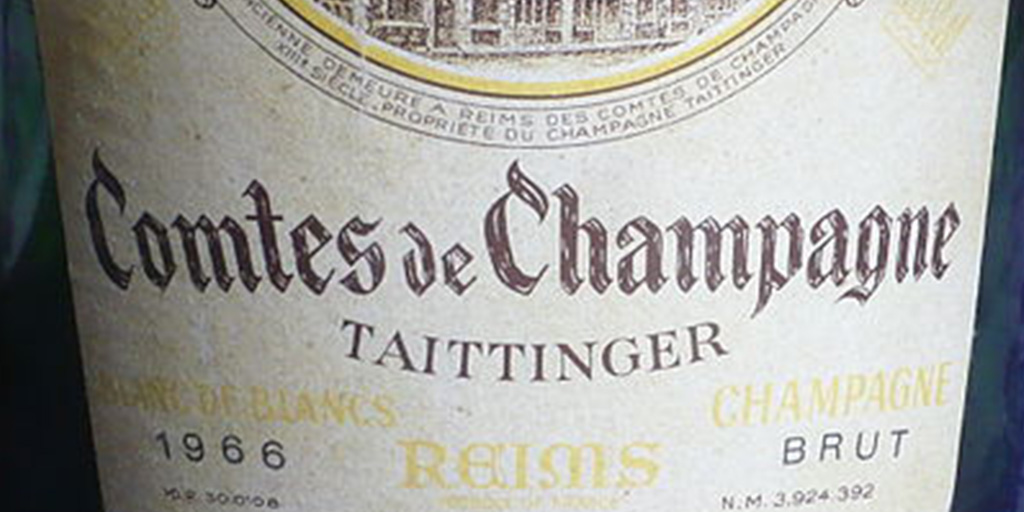

He studied the label on the bottle. It was a delicious, full bodied Meerlust that they had bought in Stellenbosch the previous summer. Putting the holiday on the back burner he thought he might suggest to his wife they drive to Stellenbosch over the weekend. He was glad that she seemed happier and wouldn’t want to overwhelm her. Baby steps he reminded himself, cringing at the words. He’d gone to university in Stellenbosch and loved the region. It was also where he met her. She’d been one of the very few students of colour, and after seeing her at one of the bars reading in a corner one afternoon he’d fallen hopelessly in love. For months she’d given him the cold shoulder until reluctantly agreeing to a date when she found him waiting for her outside her dormitory. They had taken a walk and it was there he started learning about her life. The deaths of her parents, living with a grandmother on the Cape Flats, her love of children, her shyness, when he took her hand and held it as they walked, blissfully unaware at the looks of disapproval he got. When she turned from the stove the mushrooms now simmering in her white wine sauce her smile reminded him of why he could not stay away from her.

“Why don’t you set the table for us? I’ll go shower. I promise to smell much better afterwards.”

She giggled. Throughout the meal they talked, and when he suggested a drive to the wine region that weekend, she happily agreed. That night they made love tirelessly, only stopping when they were sweaty and exhausted. He fell asleep with his hand on the inside of her thigh and when he woke up the next morning, he found her out on the balcony, drinking a coffee and reading a book. They got ready and drove to Stellenbosch via Muizenberg, taking their time getting there.

There was still time to spare before their tasting. So, they decided to take a walk on campus, across the red square, passing the admin buildings, and then stopping to kiss outside the Ou Hoofgebou. The rest of the week his wife was insatiable, her desire for him even stronger than in their courtship days. They made love in the shower, on the kitchen floor, in their bedroom, in the car, on any available counter, panting and exuberant. It went on for days, their breathless love making reaching a crescendo the following Friday evening after a gala dinner for Cape Town lawyers. She was straddling him on the couch, riding him furiously, him taking turns to kiss her neck, her mouth, sucking on her nipples when he had looked at her and suddenly felt like he was looking at someone else. It was the unusual arch of her neck, the strange glow in her eyes, the flexing of muscles beneath her skin that for one crazy moment under his fingertips felt like something was moving inside her.

The first warning was the phone call. It came the Sunday after the gala. Sanita called her phone while she was in the shower and when he answered she was hysterical. The boy his wife had taken to the hospital had disappeared. The orphanage had been searched top to bottom. The police had searched the nearby factories, hospitals, and streets to no avail. When he told her about it, she called Sanita, trying to calm her down on the phone. All the while saying,

“I’m sure there is a good explanation for this Sanita. I will find him. We will find him.”

He held his wife in his arms until she fell asleep, and the next morning when he woke up, he found her staring at the ceiling, her eyes blank. Twice that day he called from work to check on her, see if she’d heard anything. Two evenings that week she came home later than usual explaining that some of the kids at the orphanage were uneasy about the disappearance and that she stayed to restore calm. A month passed and they had given up on finding the boy, the police had no leads and none of the junkies in the nearby abandoned factory seemed to know anything. His wife worked longer hours and one afternoon he decided to leave work early, pick her up from the orphanage and convince her to go out to dinner. He was driving up to the orphanage and passing the big park down the hill from it when caught sight of her under a tree, talking to a stranger. Slowing the car down, he pulled over to the side, his aim to get out. The first thing that struck him about the stranger was his outlandish height. Arms and legs thin and wiry attached to a body with skin so pale that from a distance he looked like a mime. And then there were his clothes. Eccentric to a point of being theatrical. Black suit, black hat, black shoes, reminiscent of a village undertaker. But that wasn’t all. Even from where he was standing, he could see his wife was upset, the tenseness in her body contrasted by the mocking smile of the stranger who looked at her through mirrored glasses concealing his eyes. He called out to her, but she didn’t seem to hear him, and walking back to his car he thought he would call her, knowing she always had her phone on her person. A car sped past him before he could cross the road and then he heard his name. Turning back, he saw his wife walking towards him. The stranger was gone.

“Who was that man?”

“Oh, he was looking for directions.”

“Directions? He seemed…

“Yes, he seems strange, I know. What brings you here?”

“I thought you could do with cheering up. How about dinner?”

When they arrived at the orphanage to collect her bag, they found Sanita talking to police officers in tears. The boy had been found. His body mangled and burnt in one of the abandoned factories on Protea Boulevard.

“They say it was a ritual, like he was some kind of offering. No arrests. All the people who lived in the factory have disappeared, and it’s hard to trace them. Oh God… oh my God… burned? An altar?”

His wife put an arm around Sanita and led her inside the building. The officers stalled and he thanked them, saw them off, and followed the women into the orphanage too shocked to entertain a coherent thought. The days dragged on; the story of the murdered orphan being swallowed up by other horrors.

He came home one evening to find his wife, made up and wearing a new dress, smiling as she cooked, humming to herself.

“You seem chirpy my darling. What’s happening?”

“I am pregnant! I found out this morning!” He froze for a moment, staring at her loosening his tie. She walked over.

“I know you are afraid. So am I. But this time, it’s going to be fine.”

“Yes, I am terrified. What if…I know I should stay positive, but can your mind and body take this again?”

She nodded reassuringly.

“It’s going to be fine. I promise.”

The first month passed. Then the second. He was so nervous and alert he started sleeping badly. Attuned to his wife’s every breath, move, tone in her voice. He started praying, something he had never done in his life. During lunch breaks he would walk into churches, speak to vicars and priests, sit down in pews, praying fervently. He would stand outside mosques, closing his eyes at the sound of the adhan. Silently hoping and praying. The third and fourth months passed, his stomach in constant knots, waiting for a scream, a phone call to tell him that this baby too was gone.

He didn’t start breathing easy until month six, when his wife’s blossoming pregnant health and beauty put him at ease.

I conjure up those days now with desperation and urgency, one of the only things that keeps me going. That, and hope.

Our daughter was born on a spring day, at 10 o’clock in the morning. We named her Adessa. Perfection from head to toe. The nurses handed her to us beaming, talking about her excellent health and great vitals. When we took her home, it felt like a grand circle had been completed and both my wife and I would spend hours staring at our baby in awe. My parents who very rarely came to see us, would now find any excuse to come by. Laden with gifts for mother and baby. Adessa took a particular liking to a bee stuffed rattle and as soon as her little hands were able, she would grasp and shake, our adoring eyes always on her. Some nights I would wake up to find my wife in the nursery watching Adessa in her cot or sitting with the sleeping baby in her arms, kissing her forehead.

On the day of Adessa’s six month “birthday” my parents called my office to ask us around for dinner. I immediately agreed and called my wife to let her know that I would pick her and the baby up after work. Not getting an answer I texted and continued working, telling myself to call again in an hour or so. Two hours later I still could not reach her and decided to call Sanita.

“Hello, Sanita. Yes, I am well, thank you. Have you seen-”

“No not today. I saw her yesterday. Well, not really, I mean she was in the park down the road.”

“The park?”

“Yes, she didn’t see me, but she was talking to a very strange man. He was very tall and odd looking. I thought he looked-“

Without knowing why, I felt petrified and abruptly ended the call. In all the years of driving I had never driven so fast and with such little regard for my safety or that of others. The flat was empty and when I asked the concierge if he had seen her, he said that she left with Adessa after I left for work early that morning. I called and called her phone, standing in the foyer, the concierge casting concerned looks in my direction. I called my parents to see if she had maybe taken a taxi to their house. No. I went back upstairs calling her phone every 10 minutes and waited.

By nightfall I had still heard nothing and called the police. The following morning, they came by to ask me a few questions, but I wasn’t of much help to them and got into my car driving the streets, ignoring calls from my parents, eyes peeled and heart pounding. I drove back only after dark, feeling utterly hopeless, dialling my wife’s number. Repeatedly, leaving desperate and furious voice messages. I went downstairs again, with an aim to get back into my car and comb the streets, perhaps drive to the police station. Passing the concierge, I greeted and noticed that he was drying up some water on the floor with old newspapers.

“Some idiots wet the floor and just left it. It’s dangerous,” he grumbled.

“Any news about your wife? Where could she have gone?”

I was about to answer when an article caught my attention. Bending down I pulled the newspaper sheet closer – it was the story about the boy from the orphanage on the day his body was found. A crowd amassed outside the factory, police and sniffer dogs shrouded in a halo of flashing cameras held by journalists eager to get the best angle on the tragedy. But none of those grabbed my attention. It was the man in the crowd. The pale, tall man with his mirrored glasses. Even with the grainy quality of the photo I could make out the faint smile on his face.

It has been two years. Two years of searches to no avail. I go to our bench often where I sit for hours. Waiting. Waiting for the tall man. Waiting for God. Waiting for the Devil. Waiting for whoever to bring them back to me.