I Want To Go Home by Miki Lentin

I Want to Go Home

I lay on a stainless steel tray, the ones that butchers use to display pieces of meat. A scratchy gown tied around my neck covered my front. My arse exposed and cold against the steel. My head freezing. My body prickly with goose pimples. I shivered.

Why was it so cold?

Are you cold? A nurse asked rubbing my bare arm, her body close to mine so I could almost feel her warmth. I was parched. I hadn’t drunk anything that morning. Do you want to warm up? I nodded, and as I did, a blast of hot air rushed into an inflatable mattress made of plaster-like material, lathering my body apart from my head with heat as if I was slowly being defrosted, moulding against my sides, squeezing my arms against my body, locking me in.

I was stuck.

Just like that walk I went on with my father when I was eleven, when we got lost in the snow.

Nausea rose from my guts.

And as my body lay still, waiting for my heart to be healed, the mist, the lonely shivering feeling of being lost, huddled together, looking for a way out, came to me.

At that moment, I couldn’t quite remember how I’d got to Barts Hospital in the centre of London, on the edge of the meat market. Where blood is washed into the drains, where butchers’ whites are stained red, where entrails are tossed into bins. The day was air hair-dryer thick, the brightness of the sky made my eyes water. My head was heavy, hungover, fuzzy. How had I come to lie on this freezing steel sheet?

I turned my head and saw machines displaying blinking numbers and graphs and charts with some names I didn’t understand; suction, steriliser, evacuator, concentrator, defibrillator, c-arm, ventilator. I stared at them until they blended into a silhouette of the derelict, cavernous Hellfire Club in the Dublin Mountains where we’d walked that day.

I counted five, maybe six voices. Some behind a glass screen. Some scuttling around my body. One of the machines printed a till like receipt that the nurse tore off. Trainers squeaked. A medicinal, metallic smell of iodine. No windows. Automatic doors whooshed open every few seconds.

M had dropped me off two hours earlier. Tears had rolled down her cheeks. I told her I’d be OK, to stop worrying. If you worry and cry it will make me cry. I’ll call you and the kids when I’m free to go, I’ll see you later. Her fingers gripped mine until the last second. My arse slid onto a plastic chair in the waiting room, copies of the morning Metro lying dog-eared on the ground. Opposite me a bald man with blood blisters dotting his scalp sat bent forward, his head in his hands, as if all his life was there, between his knees.

You had to walk three miles a day. That was the rule, the doctor’s rule. Sometimes we’d walk around the block and sometimes around the park and sometimes we’d walk in the mountains.

I wanted to shut my eyes and drift off, but there was too much pulling and shoving and fiddling going on. I was being prepped. Velcro straps applied to my arms, tight socks snapped up my knees, my groin shaved, clips clasped to my fingers, my glasses removed, canular in my wrist, drip attached. I watched a drop fall from a bag of liquid into a translucent tube and wondered why it took so long for each heavy drop to slowly collapse, one, after the other.

It was a Sunday, you said you needed to walk, I agreed. We always walked in the mountains on a Sunday. Saturday was going to town day, but on Sunday you read the papers, returned to bed, had a bath and walked after lunch. I told you that it was cold, and I didn’t want to go. I’d already played football that morning and was exhausted, I said, sloping against the bannisters. I had homework. But my mother insisted. Keep your father company, but really, I knew that you had no one else to walk with. Why me? I mumbled. Why me?

Can I? Yes, the nurse brought her face close to mine. I could see her make-up caked onto her cheeks, covering dark circles under her eyes, too many late shifts. Her smile was warm, her breath sweet, her lips sticky with sleep. A nurse’s watch that was clipped to the chest pocket of her scrubs dangled in front of my eyes. It had one of those tiny second watches in the middle of the watch face, where the second hand rotates at speed. I stared at it, mesmerised that something so small, so accurate, so perfect, could move so fast. 8.30am. Yes? she asked. Can I get a drink of water please? Sorry, you have to wait until we finish. But I’m… I coughed. Doctor’s rules.

Wait. I’d waited months to get this heart ablation done. Delayed. Date. Delayed. Date. Lockdown. And then one of those NOREPLY texts that said that my operation has been postponed and there was no news when it would happen and don’t contact the NHS as they can’t help now. My GP wasn’t taking calls, so I was stuck, in limbo, waiting to be treated. But then one day, a call. Are you available? When? In three weeks? Have you been taking blood thinners? Yes. And now this procedure that I’d thought about in minutiae in my head, that would correct the jumpy beats of my heart, put it back together and stop me developing something more serious had arrived. I’d spent months wondering about the slice they’d make to the flesh of my groin. Would it hurt? Would blood spurt from my leg? Would someone speak to me while they were fiddling with my heart? But as I lay there on the serving tray, my body stiff, I felt jittery and alone. As if I was no longer in control of my body. I’d passed control on, to the voices around me.

What are we waiting for? I asked. Don’t worry, the nurse rubbed my arm again. We’ll start soon.

Overhead, a buzzing circular light, like a discus. My eyes drifted around the edge of the light, circling, until the disc became a shadow against the ceiling. My vision glistened with fractals of yellow, splodges of blue and oily filters of red, orange and crimson. Looking at the light, I felt as if I was about to float off. I had that feeling I’ve always had since I was a kid of wanting to have a bird’s eye view of my body. To see myself from above, to float, to see what the light could see.

You parked. It was just after two, but the car park was emptying apart from a few walkers who were returning from their treks with their dogs. The winter sun was low and stubbornly shone into our eyes, glimmering above the horizon. We started to walk along the gravely path towards the now burnt out Hellfire Club at the top of Montpelier Hill in the Dublin Mountains. A building once used as a den of iniquity by dabblers in black magic, debauchery and Satan worship in the seventeen and eighteen hundreds, or so legend has it. I’d never been inside. You said it was unsafe, even today, full of yobs, drunks, lads who smoke, take drugs and drink straight out of bottles. You never know what might happen to you in there, you once said. I never understood why we walked to the Hellfire if you didn’t like it? Perhaps you wanted to peek inside, see what it was really like. But you could never be tempted in, and it was easier to avoid it if I was there, even though I sensed that it intrigued you as much as it did me.

Now, a little bit of local anaesthetic, the surgeon said. I moved my eyes from the light and looked towards my feet where I could just about see the point of a syringe being pressed into my groin. Numbing drip on my skin and then, scratch. I didn’t feel much and wondered if they’d notice the stretch marks pocketed around my groin, my fleshy thighs, my hairless legs. I wanted to cover up, my balls, my knees, my feet. My arms were stiflingly hot by now, tingling with what felt like sunburn that zipped down my sides. My head still cold. I wriggled uncomfortably, unable to move, stuck in this position.

The cold wasn’t bitter, but a steely breeze rushed onto our faces every few minutes. After a while the sun faded into a blurry disc, and the sky turned dishwater grey. Wind whipped the tops of the pines that danced on the edges of clouds. Birches swayed. Trunks creaked.

Going towards your heart now, the surgeon said.

I had watched an animated video that explained that to get to the heart, the surgeon needs to thread two flexible tube like catheters, with a cauteriser and a camera at the tip of each one, through the femoral artery that travels from the groin to the chest cavity and heart. So far, apart from the scratch, I hadn’t felt a thing. There are no nerve endings in blood veins, but I wondered how perfect the lens of the camera has to be so it can send sharp images to a flat screen monitor that the surgeon glanced at in front of him every few moments. There, on screen were my insides. Insides I’d longed to see, become acquainted with, feel for myself, but I couldn’t make much out. All I could see on the screen from my position was a mix of red and black, blobs of moving objects that all looked the same, floating, bobbing, sloshing in a bubbly soup.

I’m at your heart now, the surgeon said.

A cloth sheet was clipped to the arm of a tripod and placed in front of my face. I could no longer see the machines or the monitor or the pulling and tugging that was going on at my groin. The now numb bottom part of my body felt strangely detached from me.

You and I were never prepared for our walks in the hills. I would jealousy look at other walkers in their laced-up boots, waterproof jackets and walking poles and back packs that no doubt contained flasks of tea and snacks. And socks. Oh, those socks. Thick, luscious socks that stretched up the calves of walkers over their trousers. And there we were in our trainers, you in white Asics and me in tennis shoes. You wore a grey scarf wrapped around your neck, a duffle coat, and a pair of cords. I zipped my hoodie up to my chin. You marched ahead, said there was a three mile loop you were keen to do before it got dark. I followed, running after you every few steps to keep up. The route took us into a thicket of trees. My trainers snapped twigs as we walked up a steep track. The ground smelt of bog, fresh and moist, like a wet dog. After a few minutes we emerged through the trees and stopped at a pylon, where on a clear day you could see the city stretch out below and the red lights of Poolbeg Power Station.

I was now being prodded with invisible hands, played like a puppet. Needles were threaded further up a vein into my chest. And as they were, I sensed a pressure. A weight. A force, like something was rummaging in my insides. A spider spindling behind my ribs, tickling me, a lightweight pinball ricocheting, skipping from rib to artery to muscle to sinew to vein, the threads and tubes being controlled by a gloved surgeon. A puppet master, standing at my leg, using a spring loaded lever to pull at me, yank me about to his command. And me, unable to see a thing. My body now sickly hot, my head still frozen.

We walked. You with your hands in your pockets, me now dropping behind listlessly kicking stones, like when I used to kick pebbles under moving cars, enjoying the hollow sound of them rattling and echoing under chassis as they drove past. Five minutes later, you took an apple out of your coat pocket, shone it against your cords and once you’d examined its shininess, bit into it, the juice from the fruit glistening your bristly chin. You always ate apples down to the core, nibbling the fleshy edges meticulously before crushing the core with your teeth, until all that was left were the pips and stalk that you tossed onto the dense forest floor that filled the edges of the path. You didn’t talk that much, at least not on this walk. As if something was bothering you.

The pressure dropped, as if it was about to rain.

The pressure in my chest intensified.

My skin felt like it was now being stretched from the inside, and at any moment I’d see a wire or a finger protrude through my skin. Everything felt taut, snappy, wiry. The weight on my chest increased. I coughed. I wriggled with discomfort. Are you OK? another voice said from behind the screen. Are you OK? asked the nurse. I eyed the heart monitor to the right of my head that blinked and beeped. 59, 58, 57, 54. Why is my heart at 54? I asked, my voice raspy. I don’t know, the nurse said. Do you want me to stop? the surgeon asked from behind the screen. I don’t know, I wanted to say. No, I hesitated. If we stop, you’ll only have to come back. Is it safe? I asked.

My hands were now red raw. My toes tingly and feet squelchy in my damp socks. I asked you how much further? I asked the nurse how much longer? Come on, don’t worry, you said. Try not to worry, the nurse said again. Come on. Let’s get to the Hellfire Club. I’m at your heart. Keep up. Stay with us. I am.

And then it started, the snow that is. It had crept in on us. A few damp patches on my jacket at first, and then tufts drifted onto us from the tops of the trees as they hit the ground. Gradually the snow became thicker, heavier, stickier. It whitened our coats, shoes and trousers. Thick handfuls, stubbornly not melting, like fuzz. But you had to walk, every day, and I’d agreed to come, so we kept going. I’m cold, can we go back. Come on, you said. We’ll be there soon and then we’ll go. But how will we get down? Don’t be ridiculous. We’ll loop around. We always get down.

Starting to cauterise, the surgeon said.

I’d read that a heart ablation burns scar tissue on the muscle of the heart to block irregular electrical signals and the palpitations I’d been feeling these past few months. Burning my insides, charring me from the inside out. What happened to the bits of burnt tissue I wondered? Did they float away among my insides, evaporate into nothingness?

Press, the surgeon said. And at the moment, someone, I couldn’t see who, pressed onto my diaphragm. I started to hiccup. They’d warned me of this. Three minutes of hiccupping to create space in my chest cavity, to get to the left side of the heart where the irregular signals were coming from. To help me relax, they said, but it felt like I was trapped in an airlock, air spurting from my lungs.

You and I continued to walk up hill. There was still some give in the snow. Our shoes dug into pristine whiteness leaving footprints that would soon be covered. I could see the Hellfire Club at the top of the hill, its grey stone that was usually covered in ferns and moss, now sprinkled with snow. OK, let’s stop, you said. And at that moment, I looked up at you. Are you OK? I asked. Your usually blushed cheeks were pale, your eyes were blinking rapidly, your glasses water-stained. My head is cold you said, rubbing your bald scalp with your hand, and then you wrapped your scarf over your head. I laughed. What’s so funny? It’s just… you look funny. Thanks a lot, you said. Come on.

The hiccups continued. I gasped for air, my body juddering.

We walked uphill for what seemed like half an hour. The snow intensified. I could barely feel my toes, my fingers, my lips. No one else was out. The sun had all but disappeared. Every so often snow crashed in large clumps from the trees making me jump. The snow was now ankle deep, so you slowed your walk. I noticed your breathing had become laboured. You stopped every few minutes and bent over, as if to relieve a stitch, and stuck your tongue out of your mouth to try to catch a few snowflakes for water. My nose dripped. My eyes watered. My ears frozen.

We climbed another fifty metres before coming to a fence covered in heavy vegetation blocking our way up, the Hellfire Club now invisible behind the mist and drifting snow.

I can’t get to the left side.

What? I asked.

I can’t get to the left side, the surgeon said.

Call Professor Hunter. Now.

54, 52, 50.

Shoes squeaked, the light above me flickered, the door to the theatre whooshed open, closed, open.

What’s going on? I wanted to ask, but all of a sudden there was no one to ask.

Where was everyone?

There was no one near me, at least not that I could see.

Muffled voices came from what sounded like another room, probably looking at my insides, noticing an anomaly.

Something was wrong.

50, 52, 48.

Leaping now, my heart was pounding.

Sweat dribbled down the side of my forehead wetting the inflatable.

My head was still frozen.

Where was everyone?

And then the light above me went off, as if a bulb had sizzled and blown.

Hello? I coughed. No answer. Silence, apart from the beeps from the machines. Time slowed, became heavy. And at that moment, I felt very much alone, abandoned, and all I could think of was that walk, and that we were also alone, unable to find a way out, in a mist that had enveloped us. A steam room. Soupy. A certain kind of mist. The kind of mist you can disappear in. The kind of mist when you can’t know for sure what might be beyond the clouds. The kind of mist where you have to feel your way through the drizzly blank greyness with your hands. The kind of mist where even the droplets of water that teeter on the skeleton like branches of trees look heavy, almost blue.

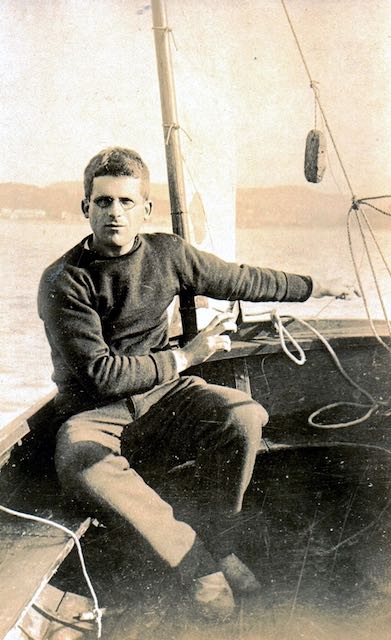

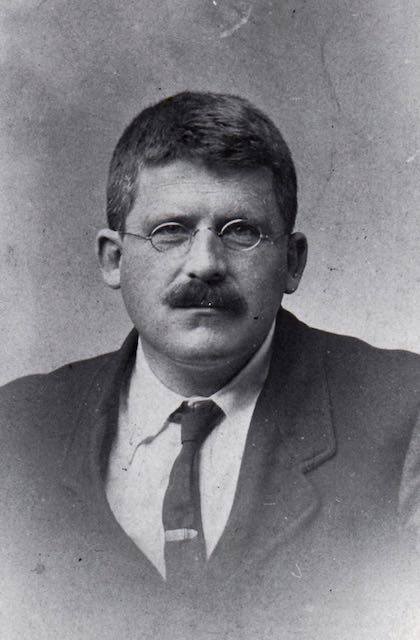

And then I’m a child again, alone, looking up at you, wired up, strapped in, lying on your own steel tray, like all the times I saw you in hospital, blood sodden bandages wrapped around your groin, staples holding your chest together. No one else is in the ward. Machines beeping. I rest my head on your warm chest, your chest hairs tickling my face, your body so big against mine, hot tears dampening my face.

We can’t go on, I said. Of course we can, this is a circular route, you said. But it’s blocked. I know the way, we’re nearly there. This path goes up and then around. But I’m freezing. Ah come on, you said, it’s only a bit of snow. You won’t freeze. A few more minutes. I’m sure this is the right way. But there is no way through. Can’t we go back the way we came? I’m sure this is the right way, the paths are circular, they’re all circular. Come on, help me find an opening.

A rush of feet. Now then, a new voice, let’s find an opening to the left side. Pressure on my chest. Hiccupping. The light fizzed back on. I want to go home, I mouthed.

I want to go home, I said. I’m sure we can get through this, you said, as you started to shake the fence vigorously trying to open it, grabbing it with both hands, as if for some reason you were determined to break it and not let a wooden fence covered with vegetation and snow stop you from completing your walk. But the fence wouldn’t budge. All your shaking did was cover our shoes in more snow.

I shook you on the steel tray. Wake up, I wanted to shout, wake up. Don’t be like this. Wake up!

And then you paused and turned to me and quietly said, I’m cold. I’m really cold. I looked at you. You were shivering. Your scarf was saturated, matted against your head. I think I need to sit down, you said. You can’t sit here, come on, let’s go, but with one arm on my shoulder you sat down in the snow, bent your knees and put your head in between them, as if all your life was buried between your knees. You untied the scarf from your head and wringed it, letting the drops of water fall into your mouth and rubbed your head. I didn’t know what to do. What was wrong with you? Why were you sitting down? Why weren’t you saying anything? We had to go, go home, get out of the snow, find our way back to the car, but you just sat there, not looking at me, staring into the snow, perhaps waiting for the mist to cover you, leaving you and me hidden, alone.

Cauterise. Camera. Pull. Left side. Hiccup. Monitor. Screen. Head. Beep. OK? Light. Lens. Hot. Cold. Pulse. Watch. Screen. Syringe. Sharp. Voices. Voices. Voices. Three, four voices now all at once. Left side. Shit. Left side. No. Left side. Got it. Cauterise. Pull. Camera. Monitor. Three minutes. Hiccups.

I helped you slowly up to your feet. We stood looking at each other. Your eyes were wet with tears. Your voice soft. Your breath smelly. I think, you said. My heart, you said. It doesn’t feel right. What should I do? I asked. I don’t know. Get some help? I can’t leave you here. Why not. You go, son, you go. I’ll be fine. I’ll wait. Follow the path back. The path I now couldn’t see. What path? You have to come with me. I can’t. I can’t move. It hurts. You have to go and get help, you said breathlessly. Run, run.

And then I just left, left you alone. I didn’t look back. I ran, my feet at first digging into the snow, bursts of snow drifting into my eyes, my heart pounding in my chest, stumbling on rocks and branches I couldn’t see underneath, reaching my way through the mist, not thinking that I’d just left you alone, not thinking if I’d ever find you again, not thinking if you’d be there when I got back. As the path turned downhill I sped up and ran like my life depended on it. As if the snow wasn’t there, lifting my knees to my chest, my arms pushing me forward, slaloming around trees, hurdling over logs, my legs brushing against each other the only sound, longing to run away, to find an opening, the wind in my face, but not holding me back. Even though it was cold I started to warm up and wanted to rid myself of my jacket which I unzipped, an exhilaration coursing through me, enjoying the freedom, the freedom of not walking, the freedom of being alone for that brief moment in the open air, forgetting that I’d left you behind sitting in the snow.

Your hand moved onto my head that rested on your chest, ruffling my hair, tickling the back of my neck. It’s only a bit of blood, you mumbled. I’ll be OK. Don’t be scared.

I ran on. And then an opening of trees to an expanse of sky. Two walkers. A dog. And socks, and gloves and backpacks. I waved my arms. They didn’t stop. I sprinted across the ground, waving my arms. I skidded. Please, I bent over breathless in front of them. Please. My father, I pointed, my dad.

One of the walkers came with me to find you while the other went for help. You were still there, still sitting in the snow by the fence, white. You hadn’t moved. Your head was still in between your legs. I was afraid to touch you, half expecting you to be dead, but you must have heard us approach because you turned your head to me and smiled, as if you knew that I’d come back.

The hiccups stopped. The screen came down. Tape stuck to the cut in my groin. Canular removed. Velcro unzipped. You’re all done, the nurse said as air escaped the inflatable. My arms loosened against my sides. My head warmed up. My toes played. The circular light blinked back on. The heart monitor switched off. You did well, the surgeon said.

The walk with you drifted out of my mind as I was wheeled out of the operating theatre, leaving the voices, the machines, the tubes, the light, the beeps behind.

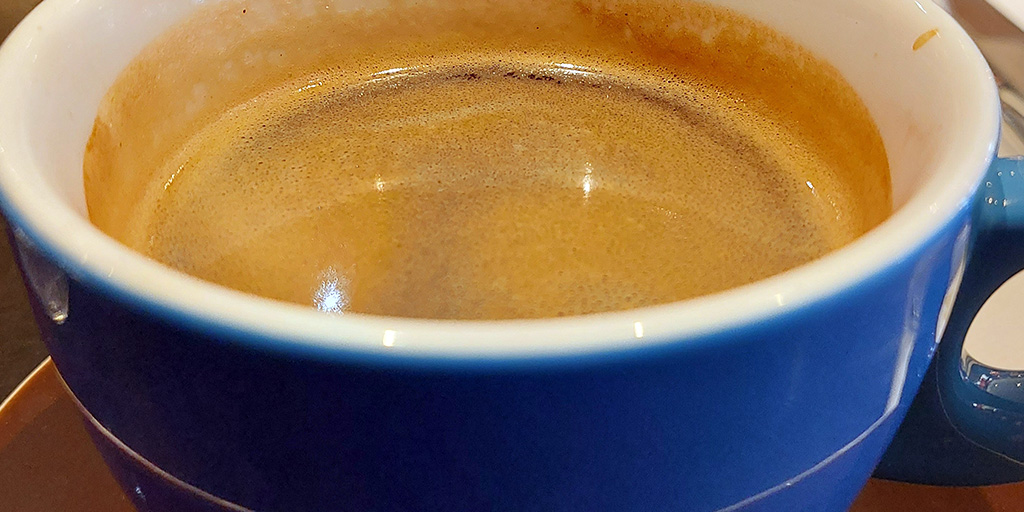

I waited to be discharged. We waited an hour. I was told I could go. Paramedics arrived. A bloody soaked bandage on my leg. A silver blanket wrapped around you. A plaster on my arm. A hat put on your head. A bruise where the canular had been inserted. A mug of tea in your shaking hands. A walk to the reception area. A stretcher to the car park. Your hand in mine, surprisingly warm.