I lean back on my elbows catching sight of the cormorant, poised and ready for the first mackerel of the day. It takes off called by a voice I can’t hear, then dives, disappearing into the sea. I’ve learnt to be patient. Lighting my pipe I relish the first taste of tobacco; its amber nectar settling me as always. When the water breaks the bird’s blackness catches my attention as it resurfaces, landing on a groyne, droplets of water glistening on its wings. Then it takes off and dives again. I try to hold my breath as long as the cormorant does. I count down one minute, maybe a few seconds more. The ocean parts as it surfaces again. Secure back on the rocks, opening its plumage to the sun. I feel Stephen next to me, as if his hand touches mine, his breath on my neck. Yet it is just the tease of the breeze. Other times when sunlight dazzles, I think I see him with his hand raised at the shoreline. But when I rub my eyes he’s gone.

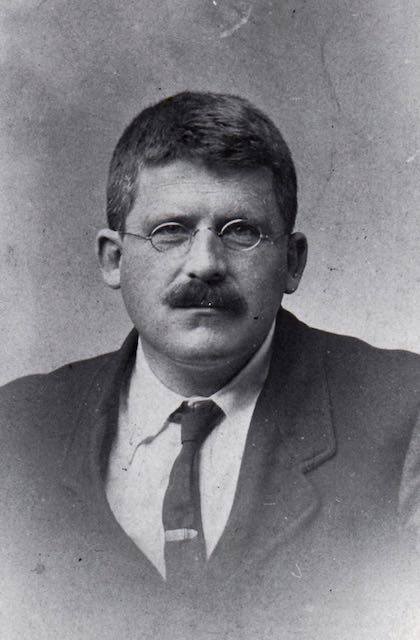

Grief takes different shapes they say. At times my imagination wanders as I lie awake in the early hours. When a tree branch taps my window I believe it’s Stephen out there, waiting to come in so we can lie once again, safe in each other’s arms. If a full moon’s shadow crosses the room, it fools me to thinking he’s come back to me. He’s gone forever from this life, but I won’t accept that he’s lost to me. Gone just after the Great War when we thought the worst had passed. When we thought we’d been spared. He was taken too soon after all he did, all he’d achieved as fisheries inspector, guardian of the sea, talented writer.

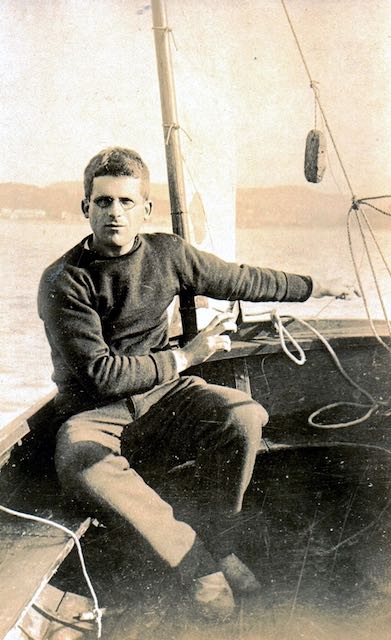

In the darkest of times he looked after us fisher folk, got us safer boats, saved lives. That is why he is remembered with love and affection even though he was not from round here. He had turned his back on a comfortable life, gone against his father’s wishes, coming here instead to serve the needs of the working poor. Stephen made his mark through his sense of duty. He was reliable like the engine he invented for his boat, The Puffin. I can still remember his smile, breaking through like the sun on an overcast day when the craft completed its maiden voyage. But at times he would retreat into himself, become short of temper, burdened by his way of life; a life we shared enduring looks and rumours. We faced them down together, from the first day Stephen and I moved in with the Woolleys.

We made an odd household Stephen, Mr and Mrs. Woolley and me, Harry Paynter, fisherman turned chronicler of these times. Our home was a sort of oasis from the everyday struggles with the sea. The kitchen with its big open hearth, a fit shrine for the hallowed blue enamelled kettle that kept us all going. There was a small-paned window in the North wall, then – going round the room – the courting chair, below the shelves laden with fancy china and souvenirs, and of course, fishing tackle. Beyond it was a walled garden cluttered with flotsam and jetsam for firewood, old masts, spars and rudders, and some weedy, grub-eaten vegetables. Stephen felt at home here amongst the debris of ordinary lives.

He was never strong of body or mind. When his sickness blew in, the February days were marked by prayers, hymns, silences and disinfectant fumes. Mrs. Woolley scrubbed the floorboards until they achieved the same bleached pallor of Stephen. Being devout she crossed herself each time she left his sick room. Whenever I see women washing their doorsteps I cross the road to avoid the lingering smell of those memories.

As Stephen got worse he struggled to breathe. The fever soaked and drained him. His lungs clogged, silted with phlegm. He drowned in his own liquid, a sort of fisherman’s death. At night, during those vigils his lungs would rattle, clattering like the sound of pebbles flung about by winter breakers on Sidmouth’s beach. In the small hours I’d listen for the creak of the stairs, when Mrs Woolley would enter with fresh towels wrapped around blocks of ice. Her tread was heavy, face creased with feelings she’d rather not share. I’d take the towels and bookend Stephen, one parcel around forehead, the other around his feet. Mrs Woolley and I nursed him with fading hope in our hearts. We saw it as our loving duty to settle him as best we could, after the sudden cold made him shake.

The sickness stalked me too, but I didn’t care if it carried me off. Since that first day I caught his eye at the fish market, I couldn’t imagine life without him. Mrs Woolley never judged or asked about Stephen and me, whatever thoughts she may have had. Her love was of the unconditional kind. She kept watch like the good soul she was.

During the last time we spent together at Stephen’s bedside, her knitting needles clacked in time with his shallow breath. The scrape of them against the yarn set me on edge. The smell of decay and sweat unsettled me. I felt the room grow small as if it was closing in on us and needed the respite of a walk to the beach.

“Back in ten minutes.”

“ Don’t linger long now.” Mrs Woolley looking up from her knitting for reassurance.

I stumbled down the stairs. Sleepless nights had drained me. In the kitchen I warmed myself against the fire. I took Stephen’s smock from behind the door, held it close, smelling a confection of him and fish in the weave of the fabric. It would be these small things that would keep me going when he left us. Pushing my cap down over my face I went to the yard, lifted the catch on the back door and felt the full force of the wind as it slammed behind me. As I walked to Port Royal men were checking boats stranded by the night’s storm. Shingle lay stacked along the esplanade, sky and sea merging into a uniform greyness. I became unsteady on my feet as a south westerly found new force. Dawn crept across the sky above Salcombe Hill. Streaks of pink flecked the clouds.

I felt the full weight of Stephen’s illness on my shoulders as a group gathered around his boat. They saw my arrival, parted and looked away. Their awkwardness reminding me of those early times down The Ship Inn when the bar, alive with banter, would fall silent as we entered. We were two men, closer than two men should be and it unsettled them. In a small town like this there was talk, knowing looks were exchanged, but these faded over the years as Stephen championed the welfare of fisher folk, got them insurance for their boats, made their lives better.

Near the sea wall a group of fisherfolk pulled and turned their nets. They nodded and I touched my cap in return. One man stepped forward.

“How’s Stephen?”

“No better”.

There was no need for further words.

As I looked back to the sea, its big breakers overtopping The Cob, I saw the cormorant dive off the shore. I paused and counted again, held my breath for the time it took for it to surface and settle safely on the groyne.

I returned to the house just in time. As a pale winter’s light poked through the sick room window, Stephen drew his last breath. The Spanish Flu had shown no mercy. I sat silently, my hand over his, as Mrs Woolley brought a mirror and held it near his lips. No beads of life marked it. She and I sat together, heads bowed. We offered up a fragment of a hymn.

“Dear Lord and Father of Mankind ”

It was his favourite.

After the formalities of doctor and undertaker the house fell silent. I was lost. The empty bed stripped of its sheets and blankets, the mattress lying exposed, the room was hollowed out by Stephen’s parting. His favourite cufflinks, with their amber stones, lay abandoned on a side table. Later that day I slept fitfully, wondering what lay ahead for me, Harry Paynter, fisherman, widower of sorts. Next morning I went down to the scullery and warmed myself against the fire. Tears didn’t come; that wasn’t our way, but I felt my heart break as I took his smock from its hook and clutched the garment close to me trying to hold onto the last of him.

In the bedroom I opened his wardrobe. Inside were the smart clothes for London, reminders of Stephen’s other life from the times when he mingled with men of letters and touched the conscience of Parliament to bring about fishing reforms. In the dresser all the clothes were folded neatly. Shirts starched whiter than the shroud that now contained him. I heard Mrs Woolley call me down for tea, caught sight of my face like an apparition in the mirror.

In the parlour Stephen’s corpse was laid out in the coffin. I kept time with him after supper though hardly any stew had passed my lips. Mr Woolley pressed a beaker of port into my hand. Its warmth took the edge off my grief and I got lost in a sort of reverie of the memory of that first time Stephen and I met a year before the war that took so many. When he picked me to work with him, invited me to share his life. Nights we spent wrapped in each other’s arms.

At his funeral people spoke quietly and warmly about him, commenting on his kindnesses, his devotion to the sea and the people who risked their lives on it. The church was packed, the ‘well to do’ alongside ordinary folk like ourselves. Mrs Woolley gripped my hand throughout.

The Vicar’s address caught the different sides of Stephen very well.

“He was a fisheries reformer but also a great writer whose work was recognized in the finest literary circles.” The sun broke through the stained glass window, shafts of gold, red and green light embracing the coffin, as the Vicar spoke of Stephen’s peculiar nature.

“Stephen could be obsessive about things like cleanliness. Indeed he hated dirt, scrubbed his hands until they were crimson, smelt his shirts to make sure the essence of soap seeped through them. Insisted they were ironed to perfection. Yet he lived and worked in a world that was full of the sweat from men’s labours and the smell of fish.”

After the funeral I went down to the beach. There would be ale later when we gathered at The Ship to toast his life. We’d sing hymns around the bar. For now I needed to be close to the water’s edge. I rolled up my trousers and stood as the sea lapped around my calves. Across the line of the bay a single trawler chugged towards home. Near the cob seagulls fought for scraps of herring.

Tomorrow I’ll return to St Ives where my life has taken a different course. Will I come back? Who knows? Yet wherever I am my thoughts will carry his memory as a precious thing tucked into my jacket pocket. As I scan the horizon I see a disturbance in the water. The sea parts.

The cormorant breaks the surface, lands on a groyne and opens its wings to the sun.

David Lloyd IS based in East Devon, WHERE HE organiseS writing retreats led by published authors AND co-curateS Open mic Novel Nights. HIS main focus is historical fiction and hidden histories, PARTICULARLY lives that have not received sufficient recognition.