Melissa Fu on her process for writing.

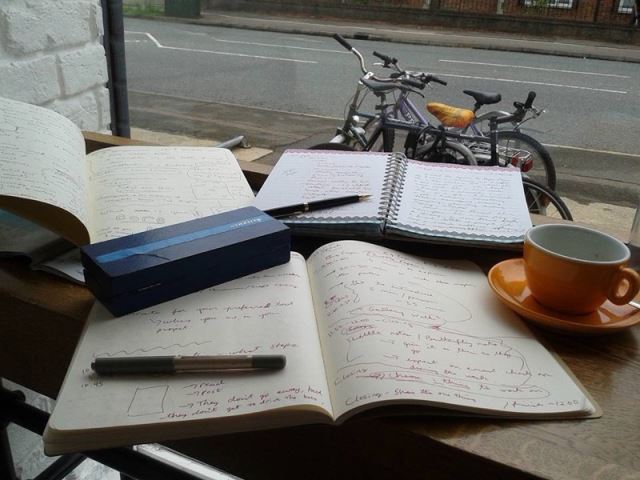

I try to write every day. I know there are divided and passionate opinions about whether writers need to do so, and as with many things that cause divided and passionate opinions, there isn’t a right answer. But for me, writing each day is a touchstone. I tend to write longhand in the morning in an unlined journal. This writing is like a musician’s warm-up of scales and exercises. It’s rarely concentrated work on a piece in progress, but it may contain some initial ideas. I like to think of this as drifting. Associations and possibilities come and go. If something catches my attention, I’ll chase it. If I get stuck, I just draw a line on the paper and pick up the next interesting idea that floats by.

There is something about the physical artefact of pages written by hand in a book that feels profoundly comforting to me. These notebooks represent my daily appearance at a place where I can hear myself and where there is nothing to justify, rationalise, argue about, apologise for, strategise or plan. It is the way I return to that world of childhood play where I spent hours outside wandering in canyons, building forts, collecting interesting stones or leaves, watching clouds race.

The writing changes when I start circling around a particular idea. When something keeps popping up in the journals, day after day (year after year, sometimes, before I know what to do with it), it’s as though it has a will of its own and must be written about.

Most of my developed pieces are sparked by an event, object or conversation that I can’t forget. These tend to be specific moments: burying glass lemonade bottles in a rose garden; eating chives and snow peas straight from my father’s vegetable patch; driving along US 285 in a snowstorm in Colorado; standing at Fiesta supermarket in Houston and hearing different languages from every direction.

Initially, I write because I want to revisit those moments.

For the first drafts, more than anything, I’m reconstructing the scene again: What happened and how do I remember it? I don’t know what the story is about aside from a very superficial categorisation. This is a story about boys with cigarettes. This is a story about fruit trees. This is a story about packed lunch. Somehow, in the act of writing, the deeper meanings begin to emerge. It usually takes me a few tries to wrangle this insistent memory or moment onto the page in some kind of readable form. Then I take a look and ask myself, Okay, what is this really about? Maybe it’s about dislocation and nourishment. Or maybe it’s about how expectations can simultaneously shape and smother us. Or it’s about being blindsided by a truth.

I can get stuck at that point. I find it difficult to generate material and shape that material at the same time. Here’s something I’ve been doing to get unstuck: When I’ve more or less drafted the piece, I get out a new piece of paper (or open a new document) where I get to explain the punchlines to myself. People say ‘show, don’t tell.’ But I tell and tell and tell. I tell all. I tell myself my answers to the questions: Why am I writing this? What do I understand? What do I want to understand? What do I think about this now? What do I hope a reader takes away? It’s like your worst nightmare of Very Earnest English major (raises hand) writing heartfelt, philosophical love letters (guilty, oh so guilty). But it works for me. By letting myself be explicit about meaning, more ideas come to the surface. When I go back to the draft where things have happened, but I don’t know why, I can think about how I want to shape that writing to better support the big ideas that prompted the piece in the first place.

This kind of ‘meta’ sidestep often helps me answer foundational questions about the piece such as verb tense, timeline, narrative stance, fiction or nonfiction. Is this a story I want the reader to relive with me in the moment? Maybe present tense, then. Is this a memory whose meaning has transformed again and again over time? Perhaps I’ll try a variety of past tenses. I quite like the exercises that involve printing something out and chopping it up into pieces to move around on a big table. The order of events and the order of storytelling are not necessarily the same thing.

Choice of narrative voice is tricky and mysterious. When I first started writing, it was always first person. Over the past year or so, I’ve been finding much more manoeuvrability in using a close third person or shifting stances in different parts of a piece. ‘Head-hopping’ is one of those cardinal writing sins that I can’t quite see the crime in as long as the reader can follow. I love how Muriel Spark changes points of view on a dime in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie without losing the reader. I think my choice depends on where I want the reader to be positioned with respect to a particular character. On the character’s shoulder? Across the room with a dispassionate gaze? Inhabiting the character’s inner world?

Although I tend to start from personal experience, eventually I reach a crossroads where one way points to ‘fiction’ the other to ‘nonfiction.’ This is often late in the process because first I need to know what has become most important to me about the piece. I have to decide if it is more meaningful as nonfiction, with loyalty to the people and situations described or if I’d rather cross over to where I can access the freedoms and possibilities that come with fiction. These days, I seem to be travelling into fiction more and more.

In final stages, I draw on a repertoire of craft techniques: check for repeated words and constructions, move sentences around within paragraphs, shuffle paragraphs, adjust sentence lengths, play with degrees of detail, read it aloud. Reading aloud is incredibly helpful. If I stumble, there’s a problem in the prose. If the pace of the story is meant to be quick but the sentences are languid, I’ll notice when I read it. Each technique reveals something different about the work in progress. This fine-tuning uses a different creative channel than the splurge of raw material creation and the deep thinking of idea sculpting. At this point, I often know a lot of the writing by heart and find myself working the words when I’m out doing errands or out on a walk. These are tiny things, like wondering if readers will connect the words ‘glint’ and ‘splinter’ from a distance of a thousand words.

So, if there is a process, it’s something like this:

- Something happens.

- I can’t forget about this something. Whatever it is, it becomes a moment that matters.

- I write about it to get it out of my head and on to the page. As much as anything else, this is to get a good look at the something.

- Various meanings start to suggest themselves.

- I go through a lot of versions.

- I try it out on other readers, possibly a critique group or a trusted reader. I am curious to hear how the story sits with them, what ideas or suggestions it brings up for them.

- Iterations of 4-6, punctuated by premature submissions which usually earn rejections.

- Eventually, something settles or rises in the writing. I’m not sure which, maybe a bit of both. It becomes knit together. If I can get a piece of writing to the point where it starts speaking to other people, I think I may have something. If I get to the point where I find myself becoming a bit stubborn in light of other people’s suggestions or rejections, I think I might have something.

But, the story itself has to matter intensely to me. I have to think to myself, if I don’t write this, I’ll regret it. Without that urgency — without that soul to its seed — all the craft and cleverness in the world may result in a confection, but nothing with sticking power. Nothing worth having spent hours and energy on. At the very beginning and at the very end, it has to matter to me. If it doesn’t matter to me, why should it matter to anyone else?