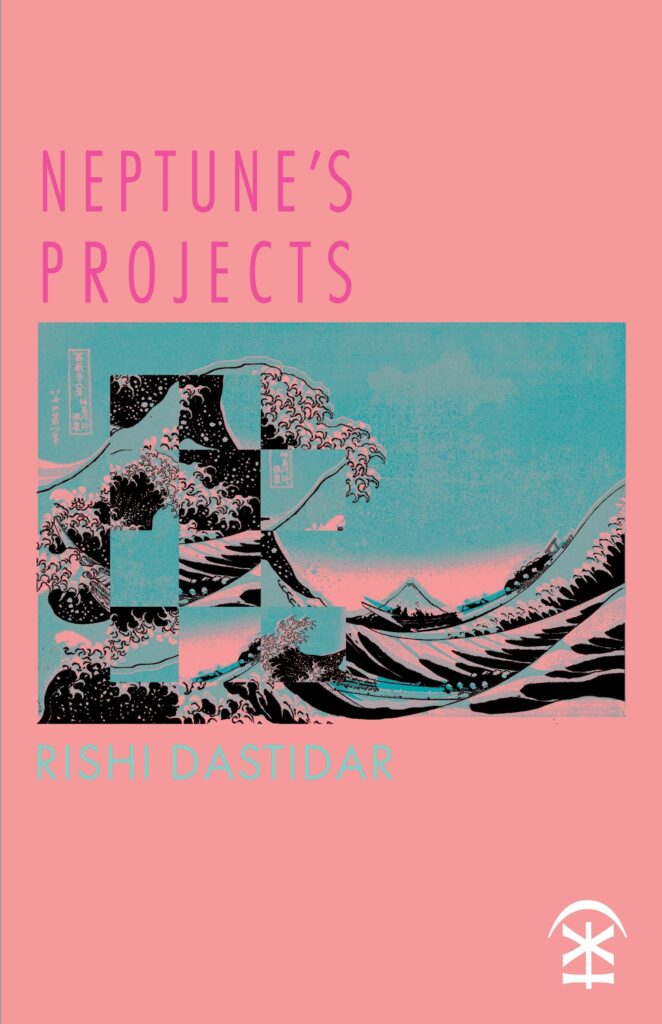

Neptune’s Project is the third collection of poems by the poet and editor, Rishi Dastidar. It looks at climate breakdown from the point of view of Neptune, the Roman god of fresh water and the sea. It is published by Nine Arches Press.

What’s your background as a writer?

Briefly, as I have been at this lark for a while: lots and lots of student journalism, then a failed dabbling with actual journalism for a few years, before I discovered copywriting for advertising and brands. While that was (and continues) to pay the bills, I was trying and failing to write fiction, and trying and failing to write essays. And then when I was about 30, I discovered poetry. Still failing at that, but remarkably, readers appear to be prepared to join me as I do.

How did you get into the concept behind Neptune’s Projects? What were the stages in its development? How did you settle on the idea of using the voice of a God to explore the destruction of the planet?

There was no planning or forethought. About 2018 or so, a few poems emerged that had the sea at their centre, as an object to be ruminated on (not much like what I was writing at the time) – sea as confessor, sea as destination to bring lovers together. And then when ‘Neptune’s concrete crash helmet’ arrived, that was when a light bulb went on: is there something in adopting the voice of a god, but giving him very human qualities and frailties? It turned out that adopting a persona that revolved at once about both being powerful and powerless was a great parallel for exploring subjects like climate change.

I should stress: I didn’t set out to write eco-themed poems; they came from this voice, and diving into it. Clearly my subconscious was worrying away, but it wasn’t like my conscious brain was telling me: you must write this. The book is a result of some of my far more submerged fears rising without being bidden all that much.

What can poets hope to achieve in the fight against the destruction of the planet? Do artists have an obligation to contend with the issues of society?

On the latter question: no, they don’t at all, and I’m not going to go round telling other artists what to be concerned about. But for me, as someone living and working in a society that feels – is – fucked up in so many ways, but with so many wondrous things that would have baffled and delighted our ancestors, too – why would you not want to examine that? Bluntly, I don’t think me and my travails as an individual are all that interesting; I’m far more interested in turning my creative energies and insights on what’s around me, and asking: what’s going on? Are you seeing what I’m seeing? Does this thing make you feel what I feel?

On the former: short of retraining as wind turbine engineers and/or living off grid? Practically – not much. But then: no one ever turned to poetry for policy-driven solutions for anything. We’re here to do what we always have been here to do: to tell stories about who we are as humans, what it means to be humans, to be in the world around us, the one we’ve inherited, the ones we’re making and destroying; and to make some noise about and around all of that. Confirm a few priors, shatter a few prejudices; make people think, look again. Expand the imaginative possibilities for all of us, about how we might live, and not destroy our civilization in the process. All of that helps at the margins of change, I hope. But I’m pessimistic as to how much that actually does to avert the wars and societal collapses that I think we all know are coming. All of us need to pull our fingers out to make a dent in that challenge.

There’s a palpable anger in this collection, but also playfulness and humour. How do you balance the two? Is one a function of the other?

I think so. The balance between the anger and the humour was a happy accident, but the striving for humour was not. It was a very conscious decision I took as Neptune’s voice was emerging. I felt that, through being sarcastic, world weary, through exaggeration, overclaiming and declaiming, maybe even the odd one liner or two, I could access and approach subjects and ideas in ways that I hadn’t see done before in poetry that looked at the environment.

A parallel: from my work in advertising, I well know that humour is a tool, an approach that can be deployed with some success when it comes to raising awareness, attempting to persuade. If we agree that the climate crisis is the most important challenge facing us as a species, why wouldn’t we use every potential tone or shade on the communicative register, to try and reach people? Maybe, just maybe, a black, gallows humour might change a mind or two. I appreciate that might be as useful as giggling into the apocalypse, but I felt – still feel – it’s worth a try.

Are there particular ecologists you look to to help you understand what’s going on in the world?

As hinted at in the book’s subtitle, ‘Now That’s What I call Hyperobject Ballads’, it wouldn’t exist without the work of Timothy Morton, and especially his Being Ecological. I think one of his successes is to show us that we are not separate or unconnected from what is around us. We might think – act – as if we are destined to forever bend the world to our species’ desires. But we’re not. And we’re starting to be able to see that, through the fact that we’re realising that some of what we have created – the hydrocarbon industry for example – is both bigger than we can grasp, and has more ramifications than we realised – emergent, unintended consequences.

I’ve found his way of foregrounding the fact that what we are thinking about is so big that it can’t be looked at in a straight-ahead fashion actually liberating. To me it means that we have to take – and accept – a kaleidoscope of views, approaches, beliefs that we’ll need to save us: which, when you think about how diverse humanity is, isn’t actually all that surprising. Yet it still can feel that way.

What is your attitude to form?

If I tell you that, right now, what my brain is mostly thinking about is: “I haven’t written an Onegin sonnet for ages…” that hopefully gives some indication. I’m neither virulently against form nor frothingly for it. I am boringly prosaic in that I hope that, as the language emerges, it gives a clue as to what it wants to become: a sonnet, a prose poem, a sestina (though if it is going that way, I do feel the need to give the words [or me] a bonk on the head, to tell it to stop being so silly), a roll of free verse down the page… In some pieces the pentameter or tetrameter hits you quite quickly, and it can be hard to resist finding the vessel for that; others are much more opaque, and so the listening and looking for the ‘what are you?’ clues are a lot harder.

What I love doing, whatever form I end up working in, is see how much I can cram in before the structure breaks; not for me one perfectly observed moment of stillness. Rather, the hope that the lyric is groaning full of goodies. Life is full of information, I like poems that are full to burst too.

There’s a movement toward collections of poems with a strong concept, theme or narrative. (for example, Fiona Benson’s Vertigo and Psyche, Joelle Taylor’s Cunto, Helen Mort’s The Illustrated Woman, among others). Neptune’s Projects is similarly an extended work. What are the advantages of building a collection around a single idea?

That’s interesting, as I’ve not been thinking of ‘Projects’ in that way, rather poems that are brought together – and maybe closer than I might have otherwise thought – by the voice deployed… are there advantages to this? Hmmm. To me? It’s hard for me to frame it in that way. I certainly didn’t set out to write a whole series of themed poems dealing with the end of the world in a bumptious voice; as mentioned above they emerged, or rather Neptune’s voice did; and when I realised then, it was that I leaned into rather than the subject.

The fact that that voice is capacious enough to handle planetary heat death and football relegation battles is a happy chance, and I suppose that is advantageous to me as an artist, to show that you can have many variations in approach, attack, perspective as you circle around whatever the big idea is. All that said, I’d hope there is some advantage to a reader – a clarity about what they might be picking up at least – and then hopefully lots of surprises as they move through the work.

Which contemporary poets do you particularly enjoy? Any specific collections that have moved you of late?

So many! Right now, what’s lingering includes: The Trees Witness Everything by Victoria Chang; Will Alexander’s Refractive Africa, which is language put in the service of an intellectual pursuit in the most dazzling way; and Holly Hopkins’ The English Summer is still making me laugh. Oh and Michael Conley is a voice new to me, but one I’m very excited by. Absurdism and political satire delivered with a deft, winning touch.

TWITTER: @CLATTERMONGER