Wendy Lothian met Jane Hayward to discuss her new memoir about her experiences as a teenager in a mother-and-baby home during the sixties. It is published by Matador, an imprint of Troubadour.

When I met Hayward in the National Portrait Gallery Café, she had been looking for a portrait of Queen Anne, having recently watched The Favourite. After reading The Baby Box in one sitting, I was intrigued to meet the writer. Despite the subject matter, familiar from the kitchen sink dramas of the period, the story is uplifting rather than depressing. This is due in part to the careful and precise language as well as the honesty and self-deprecating humour of the author. In person, Hayward is warm and engaging. Our conversation ranges from her views on historical fiction (she prefers the real thing) to the seventies sitcom Rising Damp (a guilty pleasure for both of us), but I begin by congratulating her on the publication of The Baby Box. So, why tell this story now, after fifty years?

‘There were three main reasons. One, that it had been around for a long time and I was fed up with it being on my to-do list. The second thing was that it was a long time, nearly twenty years since my mother died and that was a great stumbling block, with writing some of those scenes. The third thing was that I realised I had got the money to go into a self-publishing project.’

Hayward had always felt her story would make a novel, and began at first writing a dual narrative, with the story told from both mother’s and daughter’s points of view. She felt that this didn’t quite work, but persevered with different iterations, which she submitted to agents. One commented that the piece struggled not to be a memoir, which was a turning point for the project, Hayward recalls. ‘I thought: Good. I think I’m the kind of person that now and again needs to be told what she’s doing is right.’ Then began a serious process of re-drafting. ‘I knew then what I was going to do, with a great sense of certainty. I got it all out, and put more of me into it, which is a great release because as a writer you can hold your personal self back, and this time I let myself be me.’

Nevertheless, the piece was set aside for a while, as Hayward completed an MA in Creative Writing at the University of Chichester, amongst other things. However, she returned to it again and again, and it continued to evolve over a number of years. At one point a single chapter, one of the author’s favourites, became a short story, told in the first person, with the beginning and the end re-written. This was published on MIROnline, under the title My Mother’s Daughter. Jane considers this another significant point in the process. ‘I thought, yeah, gosh, somebody likes this, there’s something in it. And I needed to get it done, get it finished and get it out there.’

I ask about the writer’s choice of MA course and how she felt it had helped her. After researching alternatives, she settled on the University of Chichester. The taught course appealed to Hayward, who, coming to higher education later in life, found the structured learning helpful. Hayward submitted the short story she wrote in the second module, the darkly domestic The Way To a Man’s Heart, to the Lightship prize, winning £1,000, which was encouraging. ‘I was very pleased with myself.’

The location of the campus meant spending two days a week in Chichester, which Hayward enjoyed, and an unexpected source of inspiration, as she used to use the library to watch black and white sitcoms such as I Love Lucy.

Hayward owns a love of television comedy, past and present, and credits this with her ability to write effective dialogue ‘I think, with one other thing, that’s where I learnt how to write dialogue because also my father ran a dramatic society. So I was always hearing lines, where the story comes over just in dialogue.’

Since doing the MA, the author maintains her writing practice and has been a member of a writers’ workshop for eight years. The three of them meet every two months, and it seems to serve a very clear purpose, ‘It makes me write a new piece because the rule is you don’t submit the same thing twice.’ She appreciates the input from two very different voices, one of whom is also a very good editor. Hayward would recommend it to fellow writers: ‘I think you do need one writers’ group actually, however, infrequently you meet. Because otherwise, would you bother?’ She is also enthusiastic about the Birkbeck events on Saturday mornings, which she attends frequently.

We talk about the process of self-publishing, why she chose this route and how it compares to her previous experience. Typically pragmatic reasons determined the decision. ‘When I first started writing, you submitted directly to publishers. Then there was the rise of the agent, and you couldn’t go directly to publishers. Now there’s the growth of the independent, so you can go to those, but they nearly always have an agenda.’ Hayward decided that self-publishing was worth investigating, and was attracted to Matador by their ability to provide marketing support, which she feels is key, and speaks highly of their transparency about pricing, and the enthusiasm and commitment of the team.

The experience has been positive so far, but Hayward doesn’t feel it’s for everyone, ‘If I wanted to recommend it to anybody, I’d want it to be person to person. I think a) you’ve got to be the right sort of person and b) you’ve got to really think about it for a long time.’

One thing that gets a solid recommendation, however, is checking any contract with the Society of Authors, which Hayward also found helpful in the process selecting a publisher, and considers an essential part of the process. ‘Even if you’re not a member they’ll do it. They’ll charge you a one-off fee, but it’s not enormous.’

Hayward does admit to being a little frustrated that the narrow categories offered resulted in The Baby Box being classified as autobiography, rather than memoir.

We discuss the current seeming vogue for creative non-fiction and life-writing, and why there seems such an appetite for it. Hayward wonders whether fear of the future causes people to look back. ‘We want to make the past a better place than it was or reassure ourselves that today is a better place than the past was, one or the other.’ We agree that social media may accustom readers to prefer ‘true’ stories, but as Hayward says, with typical practicality, ‘Otherwise, of course, it’s just the publishing world isn’t it? It’s finding something new to publish.’

The author’s taste in reading is nearly always fiction about the domestic. ‘I don’t read crime, apart from Ruth Rendell on holiday. I don’t read Science Fiction at all. I don’t read historical fiction, I’ve got to read the real thing. So I read the fiction that’s going or I get a bit behind. The last thing I read was Eimer McBride’s The Lesser Bohemians.’

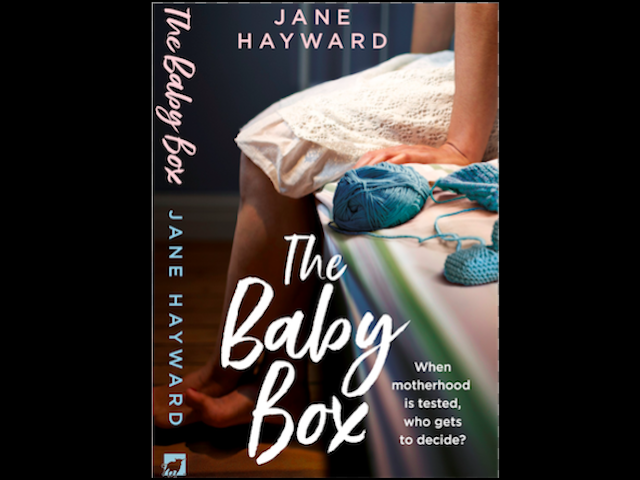

The cover image is a striking picture of a section of an interior, with a woman seated on a bed. Only her lower half is visible, and a half-finished knitting project beside her, a single cornflower blue bootee in the foreground. I feel it’s in keeping with the book, which, while it relates a most personal and difficult experience, is most definitely not a misery memoir. I ask whether this was something the publisher provided; however, Hayward’s daughter recommended a friend, a professional book designer, who worked with Hayward to create the look and feel of both the ebook and print edition. It’s clear that the author enjoyed the process and is very happy with the result. ‘It almost gets you there but not quite.’

We discuss whether, having been almost given permission to write a memoir, it changed the approach to writing such a personal subject and whether she felt a responsibility to the other people involved. While Hayward’s primary concern is to be honest, citing Wendy Cope’s view that writing is nothing if not the truth, she hopes also the reader will understand her situation. ‘I didn’t want to come over as a selfish, ungrateful person. I suppose mine is possibly a little bit different from some memoirs, in that there was another person in that triangle, the baby, and I had taken that decision, not an unusual decision, in the first chapter. There was no way that this was going to go away. So I think that’s a thing that, well, I hope hangs over the memoir; that there’s no escape.’ The inevitability of her decisions, the lack of choice at the time for unmarried mothers, as well as the judgement from others, is of course of another age and is strongly evoked by the writer’s detailed, sensual descriptions and convincing dialogue.

‘And I think that’s the biggest thing that people will find difficult. Because youngsters will just think, “I don’t know what all the fuss was about”. And even the people of my generation. I have a number of friends who got married straight from university. But that was what happened, that was normal. Well if you just happened to be pregnant when you got married…’

As well as the more pragmatic concerns of timing and ownership of the process, there is a sense that there was a more overarching motivation for Hayward to publish. ‘The other thing that was driving me to write it was that I really wanted, and still do want, people who have been adopted and who are not happy about it to read the book. That was a strong reason for me writing it: if it helped one person, I would be happy and comfortable with myself.’

I think it’s a very brave endeavour, and I wonder if anyone is going to find out the first time by reading the book. ‘Everybody except my husband.’ Reactions have been good so far, and her husband and daughter have been encouraging; her husband assisted with proofreading, and her daughter even suggested the strapline for the title: When Motherhood is Tested, Who Gets to Decide? Hayward relates that the response has been surprise that she was able to keep this to herself for so long, which in turn surprises her. ‘It wasn’t a question of how I could keep a secret; I couldn’t not keep it.’ And now that it’s out in the world? ‘Funnily enough, much easier. It’s in the book. The book is not me.’

I ask what’s next and whether she might return to shorter forms again. It seems she will, ‘I’ve got at least ten short stories about peculiar ways of dying, and the first story is about FGM. That story came out of me being somewhere where it was a 97% cut rate and yet the women that I met were so sassy and amazing.’

There is also a return to another project, related to life-writing, begun while studying for her MA. Hayward is looking to re-write, ‘restructure would be a better word’, and shorten the memoir of a family member who had suffered from PTSD. This one will be a dual narrative, with the alternative point of view of a child, Hayward as a young girl. She recalls her feelings of regret on reading the story about the difficulties he had suffered, and understanding that she had been judgemental about him as a child, motivated her to write his story.

It seems as if publishing The Baby Box is only the beginning and that there is a sense of closure. ‘I just wanted to get it out of the way. I think a lot of memoir is written like that for those reasons. You want to move on, as the cliché goes. It’s just that it’s taken me 50 years to move on.’

For more information on Jane Hayward please visit janehayward.blog