Short Fiction by Richard John Davis

“Thanks, mum.”

He says it as if acting out some sort of caricature of the rebellious teenager, even though he’s not a teenager. He has the right clothes though: T-shirt with inexplicably rolled-up-even-shorter sleeves; a purple hoodie, loosely rolled up on his lap. A teen frame too, almost skeletal. The asymmetric haircut though, the one I couldn’t bring myself to love, is long gone, replaced by a cruel buzz-cut.

He takes my gift reproachfully. He places it carefully on the floor, without even looking at it. I just hope he opens it — and appreciates it — when he gets back to his cell.

“I hope you like it,” I say.

“I bet you do, mum.”

“I don’t know that that means. And I don’t know why you have to talk to me that way.”

“I suppose you’re going to cry now.”

It’s strange. He only started speaking to me like that when he went in. Before that, he was different. He was just like any other young man, just like any other human being. He was still living with me — he went in three months ago. But now it’s different. The decision has been made.

I try talking to him a bit more, about how he is, about how this place is treating him. About how he is holding up. But it’s not working: he won’t listen. He won’t talk to me. I leave, eventually. I leave before the time is up.

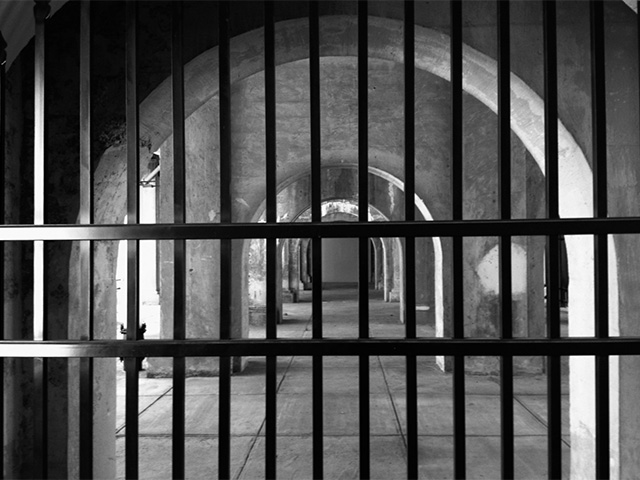

The corridor outside is long, with greyish, yellowish walls, ceiling and floor. I can hear my footsteps loudly as I walk, bouncing off the surfaces. I pass some guards. One is holding some sort of rifle, or machine gun. I jump at the sight of it. I know, though, that when I see it again it won’t shock me, not as much.

I’m not planning to visit Luke again until next week. I can only manage once a week, while he’s like this. The trouble is, in between my visits to him I’m not left with much, just musings and speculations in empty spaces. I have to actively try not to think about what he did. Thoughts of what he did to those young men and women are too much to bear. So I keep them at bay, as though they are part of someone else’s story.

The next time I see him, he doesn’t talk at all. I’m worried about him. He seems depressed. I think of all the times he sulked, running to his room and slamming the door when he was younger. Sometimes he wouldn’t come out for days.

Here he is, my little boy again.

I try talking to him, several times. I’m kind, like a mother should be. Eventually, I give up and we both sit in silence. He’s slumped in his chair, a fist pressed up against his chin, elbow resting on crossed knee. His short hair, now starting to grow through, is a little more ruffled than usual. And he’s not wearing his glasses. Eventually, the signal is given that the time’s up and I get up to leave, with Luke still slumped, saying nothing. I say a goodbye and there’s a little flicker, but no real response.

It’s like that for a couple of weeks. And then, in a moment of sudden volition, Luke seems to wake up. For the first time he actually looks at me, into my eyes.

“Why do you keep coming here?” he says.

“I’m your mum.”

“So what? That doesn’t mean anything.”

“It does to me.”

I think I see tears in his eyes. But then I see it’s just how they are reflecting in the harsh strip lights.

“Where are your glasses?” I ask.

“Don’t worry about it.”

“Have you lost them?”

“Just leave it.”

And then we’re back to silence. But I’m going to be more proactive; I’m still his mother. After our time together I ask to see someone, but I’m not sure who it should be. I want to know about my son’s glasses. I have to wait for fifteen minutes until someone appears. He’s about my age, stocky, in uniform. He smiles. I don’t like that smile. I don’t smile back. He leads me into a small room, with a low table and comfortable chairs.

“How can I help you, Mrs Nash?”

“Thank you for coming to see me. I want to know why Luke’s not been wearing his glasses. Do I need to get new ones for him?”

“Ah… I can look into this for you. Please wait here, as I should be able to get an answer for you straight away. I won’t be long, I promise.”

He leaves the room. I look around and see a noticeboard with posters and bits of paper stuck on. He seems to return almost immediately.

“Yes, I’ve got to the bottom of this, Mrs Nash.”

“Ah, good.”

“Yes, it seems that there has been a bit of a…a skirmish.”

He smiles again, but it’s not convincing.

“A skirmish? What exactly does that mean?’

“Erm, a bit of a fight. It’s ok, though. No harm done, thankfully.”

“I know what a skirmish is. Why wasn’t I told about this? What exactly happened?”

“Yes, I’m very sorry, Mrs Nash. You should have been informed about this. Did the prisoner…Did Luke not mention it at all?”

He seems to squirm a little in his seat. I make a little noise, to let him know how unhappy I am.

“And what about his glasses? What happened to them?” I ask.

“Well, it seems they were damaged in the…In the skirmish.”

“Can they be repaired? And who was involved in this fight? Is Luke OK?”

“Luke is fine. As for the other young man —”

“And the glasses?”

“Well, he’s not so good. Sorry, the glasses? Yes, they had to be thrown away.”

“So I need to get him some new ones.”

“Don’t worry about it. We can organise such things. That’s the sort of thing we deal with all the time. Unless you particularly want to —”

I get up to leave. But he wants to talk to me more. It seems that the other young man was injured, and this could mean further punishment for Luke. Possibly a court hearing. Another one. I wonder where I’m going to get a new pair of glasses from. Will he need another eye test?

Today is the first visit since the conversation about the incident, which was a couple of weeks ago. Luke is quiet again. I wait patiently, and then he seems to spring to life, as if woken up by gunfire.

“Why the fuck couldn’t you leave things alone?”

“What do you mean?”

“You know exactly what I mean. I’m not playing that game.”

“I’m not playing a game, Luke. Talk to me.”

“Oh, yeah. That’s exactly what you want, isn’t it?”

“What?”

“You’d really love that, wouldn’t you? For us to have a really deep chat. What, do you want me to talk about my feelings, mother?”

“If it helps.”

Now he’s silent again. I’m not sure what to do. I feel we might have some sort of breakthrough on our hands here: we might actually be getting somewhere. But I can’t help wondering about the glasses. I’m not sure how to bring the subject up.

We sit in silence again, for a while. I try a new line of conversation.

“So, what were you fighting about?”

“Jesus fucking Christ.”

“I’m only asking. I am your mum. I do still worry about you.”

“Why? Why, mother?” He looks at me now. “Why the fuck do you care about me?”

“You’re my son.”

“I’m your son. So that’s it. That’s all it needs. Biology. It’s all down to biology. What if we didn’t have that link?”

“But we do.”

I think about Luke at school. How he knuckled down every time it was needed. How good he was, how well he did. And then it just stopped, after his A levels. He started staying in his room more. He missed meals, refusing to come down. He was always on the computer.

“But that’s all it is. It’s just arbitrary.”

“You’re still calling me mother.”

“Whatever.”

He seems lost in thought.

“So, you really want to know why I was in a fight. Well, that’s what they call it. You really want to know?”

“Yes, of course.” I lean forward.

“It wasn’t a fight.”

“What do you mean?”

“It wasn’t a fight. That’s what I mean. They jumped me.”

“Who?”

“The two dicks who’d been staring at me all morning.”

“But this is meant to be…Who are they?”

This was meant to be a maximum-security prison. Some of the most dangerous people in the country, they said in the papers. They said Luke will probably end up in a more “suitable” place. I think they mean that it’ll be a psychiatric institution. That’s what I took it to mean, anyway.

“I don’t know who they are. But I don’t want you to try to find out. It’ll just make things worse.”

“OK.”

I do try to find out, but nothing comes of it. The prison staff say only one person was involved, other than Luke and that’s the end of it. They can’t tell me his name. They just say that Luke will be kept safe, and that I don’t need to worry.

*

When it happened, I didn’t have anything to say. That’s what I remember the most. The lack of words. And everyone wanted them from me, they were the only things people wanted from me. What was he like as a little boy? Were there any signs? Did I know what he was doing? Did I have my own doubts about him? These questions were asked by counsellors, police men and women, the local newspaper, national newspapers, friends, family. Everybody wanted to know what I knew. And I knew nothing.

That’s not quite true. I knew that Luke was caring, conscientious, hardworking. He wasn’t at all like his dad, in other words. Luke’s dad, Tim, was not hardworking. Or conscientious. Or particularly caring. He seemed jealous of Luke from the outset. When he left, taking some young work colleague with him to some new town, we hardly noticed. He was never there anyway.

Luke adored him. But the feeling was not reciprocated.

That was painful for me. Because it was painful for Luke.

But Luke was all the good things. The things you want in a son. He wasn’t what they said he was. Not before, anyway. I didn’t know — don’t know — what happened to him.

Tim left five years before it happened. He called after they announced it all on the news. He offered to come back, to visit, with his new wife of course, but I didn’t want to see him. And Luke — in a move that surprised me — didn’t want to see him either. Luke had clearly reached a turning point. Now he was inside, he didn’t need his dad anymore. Now their feelings for each other were truly equal.

So, the words never came. They still haven’t. I have nothing to say. Nothing to say about what Luke did. What he did while living under my roof.

Luke was in his room. I was watching television — The X Factor, I think it was. The police knocked hard. Three times. I could then hear a lot of talking outside — deep male voices. I walked quickly. I thought there was something going on with the neighbours, some commotion. But the commotion was coming into our house. I opened the door and they pushed past.

“Where’s Luke?” one of them asked.

I suddenly felt an accelerated alertness, as if Luke’s presence had only just made itself known to me. I pointed toward the ceiling. One of them stayed with me, while the rest went up. They all left as suddenly as they had burst in. Luke was silent as he walked past the living room door, handcuffed to a policeman. He looked tiny. He looked insignificant. He looked like he wasn’t there.

Luke didn’t look my way as he went past. I replay that scene over and over, when I can’t stop the memories coming back. Most of the time, as I say, I can blot it out. But sometimes they win. I see him walking past the door, silently. Only now it’s like he’s gliding past, slowly. It seems to get slower with every replay.

Even the one that stayed with me, a little man whose uniform didn’t seem to fit properly, left in a hurry. I was on my own. I didn’t know what to do. I looked at the television and sat down. The X Factor was still on.

Hours later, I went to the nearest police station. I asked about Luke. There were a lot of people there. I noticed some were holding cameras. Someone had clearly heard me asking about him because they all looked my way. There was a pause before anyone said anything to me. Maybe I was like them. Maybe I didn’t matter. But it didn’t take long for someone to realise I did matter, that I wasn’t like them. I don’t know what it was — my clothes, my age, my expression — but they realised, seemingly all at once. They rushed toward me, encircling me.

They asked me all the questions I was to become used to, but this was the first time. It was like the flash of a glimpsed movie before a police officer noticed what was going on and ushered me away to a private room. I wasn’t allowed to see Luke. He was still being questioned. I asked what was going on and the policeman just stared at me. I couldn’t read his face. Was that confusion? Doubt? Suspicion?

When I eventually got to see Luke, two days later, he had changed. This was the moment he changed. The moment he went inside.

I tried to ask him what he had done. His face told me everything I needed to know: a new face, grinning, hostile. The police had already run through everything with me anyway: the murders, the knife used, the obsession with serial killers (the police used the term “other serial killers”), the stalking and the “trophies”. But I didn’t want to know about it. I did, but I didn’t. I wanted to know what had happened to my son. Soon, I discovered that was what everyone else wanted to know too.

*

Luke is kept safe. After a series of assessments, he is transferred to a “more suitable environment” — a high security mental health institution for the criminally insane.

And he seems happier. He doesn’t like his diagnosis, says he doesn’t agree with it, but he likes this place more. I can visit more often, too, and for longer periods. That he doesn’t seem to like much, but he accepts it. He accepts that I’m not going to give up.

Today, he is wearing his pyjamas when I come in. He doesn’t respond to anything, so I just talk. He seems half asleep. The staff warned me about this, saying that he is on new medication and that it will take time for him to adjust to it. I can see Luke’s new glasses resting on his bedside table. The new frames are nothing like the old ones, they are more modest and understated. I hope he likes them. I look back at him, with his eyes half-open yet not seeing, his breathing slow and steady. I like him like this. He doesn’t give me any attitude. He just lets me speak.