Short Fiction by Jacob Parker

Out on the northernmost point of the Spanish Galician coast, in a large bay, relatively protected from the winds and swells of the wide Atlantic, sits the small fishing village of Porto de Baquiero. The name of the village is grander than the place itself. It may have been that its original founders saw the great potential the natural geology offered for a large port: A bay sheltered from the Atlantic by a promontory, and deep waters that would allow the entrance of large ships. But for unknown reasons, neither the Spanish nor the Moors before them took advantage of its natural setting, and so Porto de Baquiero was passed over, unnoticed and untouched. As it was the few houses of the village seemed to have grown out of the rocks of the coast, and it was lovely.

The Galician coastline falls away steeply into the sea. Dense forests of eucalyptus and pine descend down almost to the waterline. Small roads weave their way through the forests alongside the coast. In the wind, the trunks of these tall trees sway and rub together creating strange sounds like the voices of men in pain. The shoreline itself is rocky and for miles along the coast large slabs of smooth granite lie half-submerged in the dark water. During the winter months the sea is dangerous, swirling and crashing on the hard Galician stone. Locals who harvest the valuable percebes from the wave-line at that time of year, live in fear of what they call the seventh wave: a huge swell that appears from nowhere, that can take the percebeiros by surprise, and has dragged many out to sea.

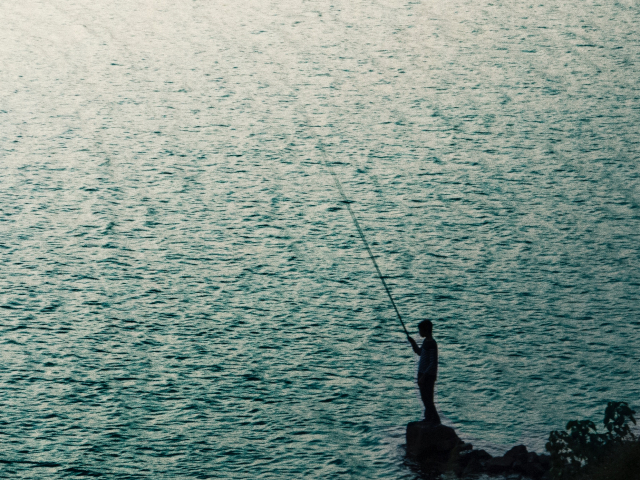

It was summer however and the waters were inviting. The sea had settled to a clear blue-green where it rocked and gurgled around the granite slabs that lay warming in the sun. An observer on the shoreline, looking down into the water, would have been able to see the sea floor and marine life quite clearly. On such days a handful of local men could be found scattered along the coast where they passed the time fishing for Sargo, Lubina, Escabelas, Dorada, and Merluza.

A few miles along the coast from Porto de Baquiero, on one of these large rocks slanting into the sea, stood a boy with his fishing-rod in hand. He was young, a boy in his early teenage years. His body was tall for his age and thin. He wore electric-blue football shorts and a white vest. His bare arms and legs were bronzed by the sun. His hair was the black hair of the Castilian Spanish, but his face carried the Galician traits of Celtic ancestors — a memory of his descent from the Kings of Ireland. His features were still young, boyish, but changes brought by his age were apparent. His nose, chin, cheeks, jaw, becoming those he would carry as a man.

The sun lay across his shoulders and the water lapped at his feet. He wound the line in, lifting the float and hook from the sea. The miñoca worm was gone again. He went to fetch another from his bag. The fact that the worm had gone was good. This meant the fish were biting. But maybe they were not big enough to take the worm and hook all in one. He held the new miñoca, wriggling, between his thumb and forefinger. He slid the hook, first into the lower half, then all along the body, so as much of the hook as possible ran through the worm. He returned to his place near the water, let the line out some, angled the rod over his shoulder, then cast out into the sea.

He had been here since the early morning. He liked that; to get up with the sun still low and the air still cool for the walk through the eucalyptus and pine trees to this, his favoured fishing place. He’d had many successes here. He was coming to know the different patterns and habits of the fish quite well. And it was here that he had also caught his first Merluza. He was going to tell his friends at school about this. They had been out at break-time, the day after he had caught the fish, and the girls had been with them again. And it was when Andres had been telling them loudly how he had nearly caught a Merluza. Irene and Maria had been there too — Maria del Mar — and he was going to say it, to tell them then that he had actually caught and landed a Merluza. But he had stopped himself. At that moment he hadn’t wanted people to look at him. And Andres had carried on, “I saw it leap from the water, it was as long as my arm”.

He watched the float at the end of his line in the sea. The red, blue, and white stripes of the float were clear to him as the sea was very still today. He hadn’t noticed any movement or felt a bite. But in thinking about school maybe he’d lost focus. Perhaps the smaller Lubina he thought he might catch had moved off. This sometimes happened as the shoals moved along the shore. And he had a choice: either he could wait until a new shoal came, or he could change to sea-fly fishing. Feeling he may have missed something he reeled the line in. The miñoca was still there, still moving slightly. It didn’t look touched. Maybe he hadn’t missed anything. He cast into the sea again. This time he’d keep his concentration.

Besides, he had overheard Maria say to Irene that fishing was so boring. That it was shallow. With the float fishing he was doing now though it was very important to think about depth. The Lubina shoaled at quite a particular depth below the surface. This was because of the warmth of the water and being able to avoid their predators at this level under water, as they were very hard to see. When he swam with his mask he had experienced this, because he could see how the Lubina would appear and disappear as they turned in the light underwater, never clearly defined against either the sky above them, or the sea-bed below. So as he watched the red, blue, and white float, as he was now, (there had still been no sharp movement, he felt fairly sure of this) he would imagine five to six feet below the surface, where the Lubina could be passing.

Perhaps he should tell Maria these things. Or perhaps that would be the worst thing to do. He thought he would like to try to tell her, if they walked home from school together again. This had actually occured a week ago. Their houses were in the same direction, and they had, just by chance, started walking together. That was the first time he had talked to her. Talked to her as in just the two of them. She had been different, acted in a slightly different way from how she was around her friends in school. But then he supposed he had been a little different too.

The float ducked! Well, he thought it ducked. Actually, he wasn’t sure. He felt no tension in the line. It could have just been the sea pulling it around. But if it was a fish, he would have missed it as he had lost concentration again. How had he lost concentration again? He began to reel the line in and there was no weight or resistance. If it was a fish, he had missed it. When he lifted the float from the water he could see the miñoca was still there. It looked entire. He wasn’t sure now. Anyway, he decided to change to the sea-fly. It provided more things to focus on. And besides it was a good time of day now to sea-fly fish. In his bag he only had one sea-fly at the moment, but he would get the other one he asked for on his birthday.

He took his pliers and cut off the float from the line and set about attaching the sea-fly. He liked her name, Maria’s. Maria del Mar. Maria of the sea. And also, now that he thought about it, at church, Father Colado said that Jesus had hung around with fishermen. And Jesus was meant to be pretty deep. At church, Father Colado said that Jesus had been a fisherman as well. In a way; a fisher of men he called him. And that Jesus then taught his disciples to be fishers of men also. Jesus didn’t seem to catch many girls either, the boy thought. But he supposed Jesus’ bait was big, and it must have been delicious to those who were hungry. He had the sea-fly attached now. It was much heavier than the float and he enjoyed casting it, as with the extra weight it went very far. His cast was a good one. A good direction. Now he began pulling the rod and winding the line continuously to move the sea-fly through the water to make it look like a real fish.

The boy thought that real fish were for certain harder to catch than just recruiting disciples like Jesus did. For example, fishing for salmon in the mountain rivers in the spring. This was very, very difficult, as to do this he had to fly fish. Real fly fishing. Not sea-fly fishing. He had practised last season for the first time with his uncle, and he had liked it very much. Fly fishing took a lot of practice to get the techniques right. A lot. More than sea-fly fishing. First of all, you had to whip the rod to make the fly dance on the water a few times. Right where you thought the salmon were in the pools. Then you let the fly rest and let the water take it. Just as if it were a real fly, resting for a moment on the surface of the water. If you could make it like the truth — as if it were the real thing — then you would maybe be rewarded.

He pulled the rod and wound the line and moved the sea-fly through the water and felt better now as he was concentrating on his technique and these actions. He still had a lot to learn about fly fishing for the salmon in the rivers though. His uncle had started to teach him. But there was not only the technique with the rod and line. There was also the craft of making the flies. His uncle had a small workshop where he made his own flies and he let the boy come and learn how to make them. The boy had made quite a few flies already, but his early ones were not very good. You had to make the fly look as much like the real fly as possible. For the salmon in the rivers in the Galician mountains, the accepted method was to use the horsefly. Horse hair was best to make this fly, and his uncle said — with a slight red dye to give the impression of the wings. Two evenings ago, he had been working on such a fly in his uncle’s workshop, and he thought it was nearly finished. He had put a lot of care and attention into making this fly. Every stage he had tried to do perfectly. He had yet to test it in the rivers, as he had to wait for the season, so its success could not be known for sure. But he thought it was just as he wanted it. It was the best he had ever made. He had tested the fly when he was in the bath as well, when he was sure his mother would not come in, to check the float and that the horse hair he had wound would not matt in the water.

Then there were the sea-flies he was using for the sea fishing now. These were metal replicas of the fish with quite a lot of the fineness of detail. And the way they were shaped meant that they moved like the real fish through the water — jagged and darting as he pulled the line. But this movement wasn’t easy to achieve either. It too still needed a lot of technique — more than people realised — to make the fish seem real. You had to move it gently through the water, the right hand reeling at varying paces all the time, the left hand pulling the rod gently. Irene said the boys didn’t care for anything but fishing. This was probably true. But she didn’t know everything about him. He hoped Maria didn’t think this about him. You must try to think as the fish thinks, imagine seeing what the fish sees. This is when you get a bite. And it’s strange, he feels, because sometimes he knows he is going to get a bite just before it happens. It’s as if everything has come together — the time of day, where he’s cast, the movement of the sea, and it is inevitable.

Catching girls must be nothing like catching fish. He could catch fish. He knew how to do it. He knew how to move the sea-fly, where to cast, where they would be, and when they were hungry. Alvaro said catching girls was just like catching fish. “It was all about the bait” he had said, as they were standing around the gates after school, and then he had winked. Everyone had laughed. And the boy had laughed as well, but mainly because the others were laughing. And anyway, the boy thought, he wouldn’t want to catch a girl (maybe a girl like Maria for example) in the way you caught a fish. Because when he lifts a fish out of the water, he can see the pain in their eyes. It is large and black. And amongst the excitement he also feels a guilt; guilt that he has deceived them. They thought it was a real fish they were chasing.

Señor Robins, in science, said that fish don’t feel pain — not like humans feel pain — because they don’t have a central nervous system like ours. It’s just a chemical reaction of their bodies, not getting oxygen through the water. But when the boy has looked at the fish he has caught, and has felt how they struggle — when he’s held their bodies down, dense and cold beneath his hand — he has not been so sure their pain is not real. This is the hardest part. When he sees their eyes wide with terror and their mouths gulping in disbelief. Also, he wouldn’t know what to do with a girl, like Maria for example, if he caught her. Take her home for dinner to his mother perhaps? Like he did sometimes with the Lubina he caught.

He nearly had one then. A Dorada jumped out of the water chasing his sea-fly. But he was too slow and didn’t react in time. It looked like a good fish, about a foot long. These Dorada could eat fish the same size almost as themselves, because their mouths were very big. He remembers how amazed he was when his uncle had told him this, and he enjoyed telling others. He wondered now if Maria would find this interesting.

When sea-fly fishing like this you could also see glimpses of the fish sometimes through the water. Because as they are chasing the sea-fly very fast, sometimes you see a flash of silver. This is the fish turning or moving quickly as it goes after the sea-fly, and as it does so its underside can catch in the sunlight coming down through the water for a moment and there is this flash. It makes sea-fly fishing very exciting as you know something is there, in pursuit. Like a clue to the things happening below the surface that you cannot see. Irene had blonde hair, but Maria had brown hair. Very dark brown, almost black. But certainly brown. You could tell it was dark brown and not black when she turned and it caught in the sun. It was when her hair caught the light and sort of flashed you could see it was actually a very dark brown. He much preferred Maria’s dark hair, he thought. He didn’t know why he preferred it. Or even when this had occurred to him. In fact, he didn’t remember ever having really noticed the colour of her hair before. He pulled the rod and wound the line and moved the sea-fly through the water, waiting for the flash of silver down there in all that blue.

The sun was beginning to fall behind the eucalyptus and pine trees and their long shadows were stretching now over the boy’s shoulders. He felt a chill at their touch. It was Sunday evening. He felt he had miñocas in his stomach, but he didn’t know why. He wasn’t sure if this was because of going to school tomorrow, like he sometimes got, or because of something else. Something new. He’d rather fish all day than go to school. Even if it was shallow, as Maria had said. Maria del Mar.

The wind was up as he walked home along the road and the eucalyptus and pine trees were rubbing together making sounds like the voices of men in pain. The wind was coming down now from the steep Galician hills, and it carried with it the green smells of the forest and the dark scents of the earth. And from further, higher, came something too of the cold Galician rivers, where he knew there would be young salmon in the shallows, waiting for the Spring — their firm bodies snaking in the current. Yes, they were waiting for him, he knew this: their bodies becoming ready. The wind was coming down, all the way from the Galcian mountains, down the steep hills of the Galician coast, sweeping through the eucalyptus and pine forests, and then over the winding road where the boy was on his way home. It swept softly, too, through the few streets of Porto de Baquiero, out over the sheltered bay with its deep waters, over the small pier of the village, and out, onto the winds and swells of the wide Atlantic.