Suki Linnell reviews Bolt from the Blue by Jeremy Cooper

London 1985. Eighteen-year-old Lynn Gallagher leaves her single mum and her Birmingham suburb behind, as she sets out to become an artist. Lynn writes postcards to her mum, or Mother as she asks to be called, from her prestigious art college. With some prodding (‘Have you got the correct address?… I’m not going to write into thin air’) Lynn receives sporadic replies. But Mother has little to say to her only child: ‘I’ve settled in. To my new hours at The Blind Traveller. And to controlling the booze.’

Meanwhile, Lynn’s letters glow with her determination to succeed in the art world. She writes with an obsessive enthusiasm about the London scene – its favoured techniques, its people, its galleries. Yet the more she rhapsodies about avant garde exhibitions, and accumulates artistic triumphs of her own, the more her mum clams up. Or lashes out, with the sharp criticism only a mother dares to provide: ‘What do I think of your… what would you call it? A picture? Don’t think much of it, to be honest. Looks a bit of a mess.’

Through clueless missives and acid replies, a picture emerges of a pained mother-daughter dynamic that is comic for being familiar. We see a repeatedly fractured, repeatedly mended relationship, just barely held together by their mutual compulsion to correspond, and to understand. Along the way, we follow an ambitious artist’s heady arc through the London scene of the 90s, 00s, and the 10s. We also discover the tics and tendencies that these two women, increasingly divided by money and class, have in common.

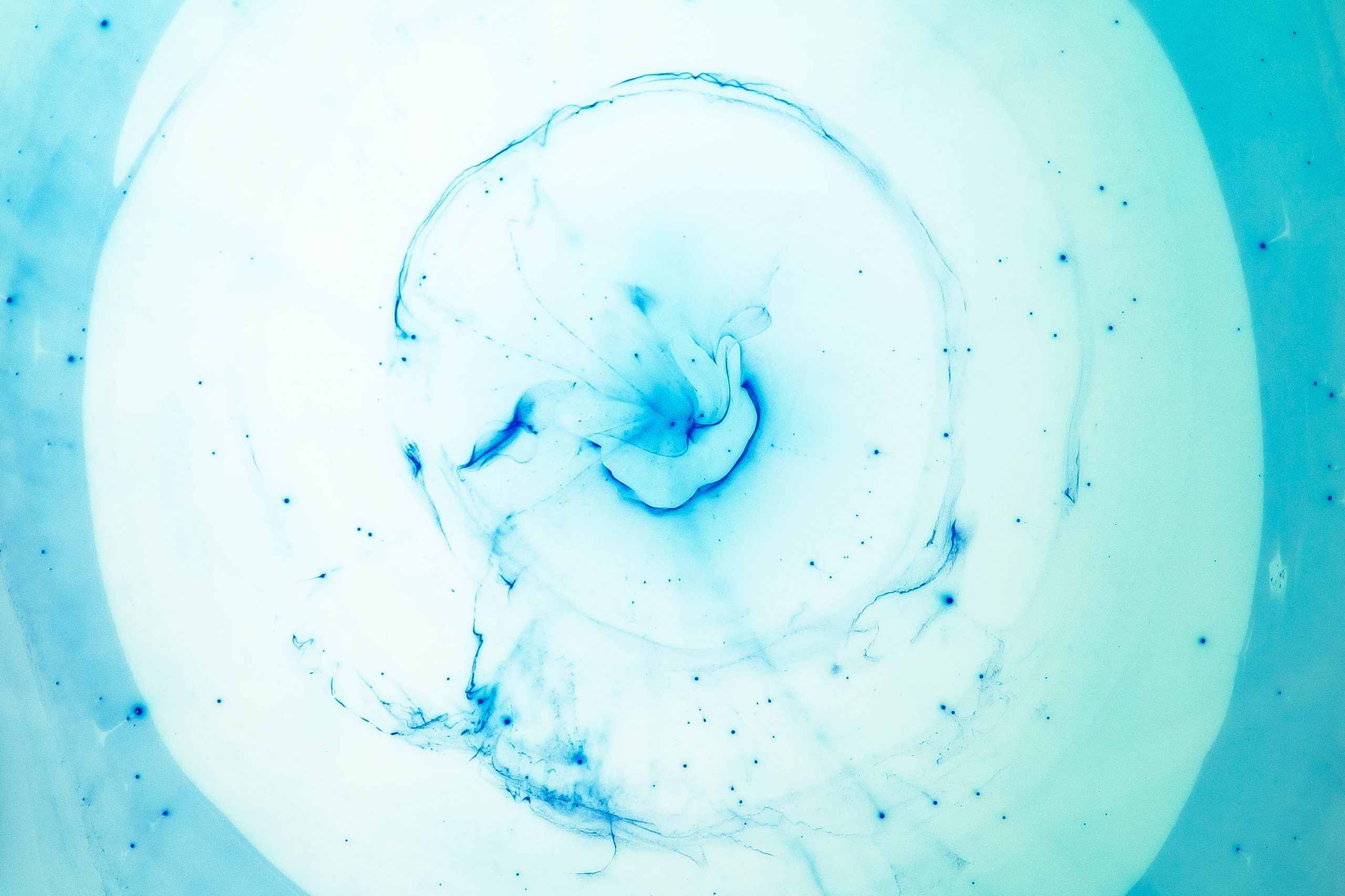

The story is told in strict epistolary form. Present-day Lynn provides a preface, explaining that in the wake of her mother’s death, the correspondence – with her own annotations and artistic descriptions of key postcards – has become her latest, and most personal, art project.

Jeremy Cooper’s previous novel, Ash before Oak, used the format of a nature diary to track its narrator’s increasingly disturbed psychological state. The use of postcards here gives the reader a curious experience – here, the expectation of the cheerful, unprivate banalities of postcards (thinking of you!) is undercut by the turmoil that Lynn and her mother bring to their exchange. Everything is breezy, until Mum lands a particularly well-aimed barb, or Lynn brags just a shade too provokingly about her increasingly Saatchi-sponsored new life, or fails to curb her solipsistic art-talk. The pair alternate between dispensing wounds and feeling injured. The length of the silences between letters wax and wane in relation to the degree of rupture each can tolerate. The reader becomes a voyeur, as though we might be the local postie, peeking at a largely plein air correspondence.

Bolt From The Blue has an enjoyable insider’s feel to it. Cooper, an art historian as well as a novelist, was involved in the Young British Artist scene, and clearly relishes the chance to revisit the iconoclasm of the artists who have since become household names. There are gossipy notes on the careers of Tracy Emin and Damian Hirst; breathless reports from zeitgeisty exhibitions that have since become ossified by praise, and tender eulogies to those artists whose lives were cut short, one way or another. Equally, Cooper isn’t precious about the art world; he skewers the pretension of its language, with entertaining results (‘These customised burettes filled with the year’s ashes of [a fellow artist’s] burnt paintings are the soul of the show, to me.’). Yet it is affectionately done. Amid the press releases that extol ‘the baroque and bombastic…contested surfaces’ of Lynn’s work, I found myself becoming curious about the real YBAs and their work, and ended up tunnelling away at various internet rabbit-holes, so I could better understand what I was reading.

The chief pleasures of the novel, for me, were its gentleness and light, skipping pace. Cooper casts human flaws as tender foibles, and moves the reader along quickly through the years, all while exploring large themes of familial estrangement, class division, ruthlessness, and loneliness. And there is no heavy, lyrical prose here. These themes come in unspoken hints, buried within chatty updates and loaded postcard choices. I became a sleuth, picking up on frequencies. And so when Lynne and her mother are vulnerable with each other, the pathos of it managed to shock me.

Despite its arty conceptual trapping, Bolt From The Blue has the texture of actual personal relations. As a result the mother-daughter relationship feels frustrating, understandable, funny, tragic, and very close to real.

Buy a copy of the book here