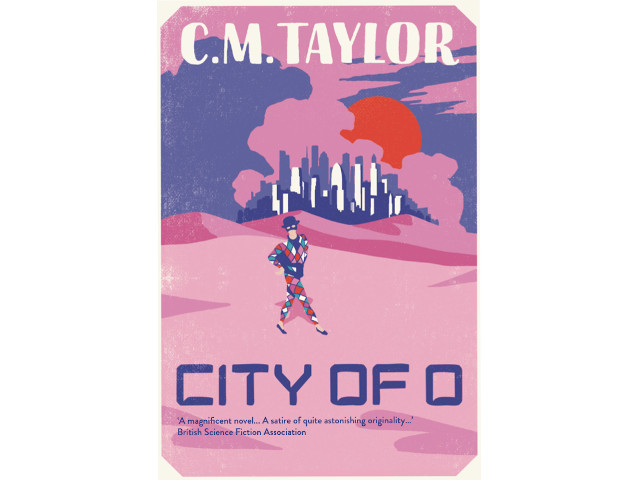

Patrick Christie reviews the re-release of City of O by C.M. Taylor

Newly orphaned, Juan arrives in the City of O, a malleable and amorphous

Metropolis, where the Sagrada Familia, Mount Rushmore and the Uffizi nestle side by side. Where beaches appear overnight and citizens pay to have the Alps moved in view of their apartments.

The moment he steps off his train at Grand Central Station, Juan is talent-spotted and invited to join the ‘Boundless’. The city, he soon learns, is a caste society with an underclass of ‘Extras’ and ‘Intransigents’ ruled over by the ‘Boundless’ and ‘Shapers’. ‘The Boundless move with the city, but the Shapers move faster than the city and they make it,’ one of his new acquaintances explains to him on his second day. ‘What was I when I arrived in the city?’ Juan then asks. ‘I thought you knew Juan. When you arrived, you were nothing,’ she replies.

In his new life, Juan binges on drugs with names like ‘forget-its’ and ‘correctives’; he undergoes casual surgery to make himself more ‘plastic’, staying on top of the latest trends by having his hair feathered and a watch inlaid into his palm. Little explanation is ever given about the mechanics of this bizarre world. Instead, Taylor avoids overwhelming the reader by presenting it all in a matter-of-fact (if wry) tone, using clear sentences that rarely stray from the simple past. (Although this doesn’t prevent the occasional literary flourishes from creeping in – ‘the sea fanned out forever and yet found time to roll into the shore.’)

City of O, was first published as Grief in 2005. Taylor wrote it in 1999, after quitting his London media job. Its age goes some way to explain the apparent parallels between Taylor’s satire and another send-up of the post-yuppie, new-media class, Nathan Barley (also released 2005). Juan’s fellow ‘Boundless’ work in schizophrenia or impotence trading; they move around the city by putting on monkey arms and swinging on netting hung between the buildings; they spend their leisure time ‘doing war’ and ‘doing culture’. Once Juan starts to make some money he invests in a piece of ‘artvertising’, which comprises three artists continually wanking in one corner of his flat.

Although Juan enjoys a meteoric social rise, it’s quickly clear he can’t take pleasure from the endless parties, orgies and superficial relationships that fill his days. Is it simply the loss of his parents that hangs over him or could it be something else?

The answer to this may lie in the other half of the narrative, which follows four harlequins – Alberto, Sansu, Louis and Gargantua – on a picaresque trek across the desert in search of Juan. Here, in their encounters with villagers, bandits and traders, the satire is replaced with openly comedic writing, particularly in the odd-couple relationship between jolly and verbose giant Gargantua and dour philosopher Louis. Towards the end of their adventure, Alberto and Sansu announce that they intend to marry and ask their fellow harlequins to perform the ceremony. In officiating, Gargantua speaks at great length, imagining a happy future for the couple in which ‘babies fall from Sansu like frogs from the sky’, complementing himself as ‘a man so strong as to knock Armadas off course with a puff of his bottom breeze’ while the other harlequins ‘stand silently, shifting from foot to foot, yawning occasionally.’ Afterwards, as best man, Louis says simply: ‘I consider marriage to be the most abominable of human institutions. Despite this, I do feel a certain degree of happiness today,’ then sits back down.

There’s much to admire in Taylor’s narrative. If the satire feels dated at times (a joke about a character joining a quango feels very New Labour), it has lost little of its bite. At one point Juan interviews the President on television. When they run out of questions, the two break into song, with the President turning out to be ‘a sexy little dancer’. The routine proves such a hit, the President becomes the co-host. With an ex-reality TV personality currently in the White House this feels almost prescient.

Any science-fiction fan that is put off by the solemn tone of much dystopian writing could do much worse than entering the surreal, absurd and frequently hilarious world of the City of O.

You can purchase a copy here