Immersed by Everett Vander Horst

Church is, I’m sorry to say, a mixed blessing. I wish I could testify that it’s been all fellowship and edification, but in truth God’s people come with a steady stream of frustrated tears and angry words as well. Over the years, Kees and I too have earned a few scars, which of course are wounds that have found healing—though they’ve certainly left their mark.

The latest struggle has centered around our dear friend Linda. Mina and I befriended her when we while we were a part of a women’s self defense class back almost two years ago. Well, with a few starts and stops, God’s really been to work in her life, for the good. Late last spring she concluded a whirlwind romance, marrying a fine man a few years older than herself, a fellow named Danny Grable. They have been awfully good for one another and have become an active part of the church.

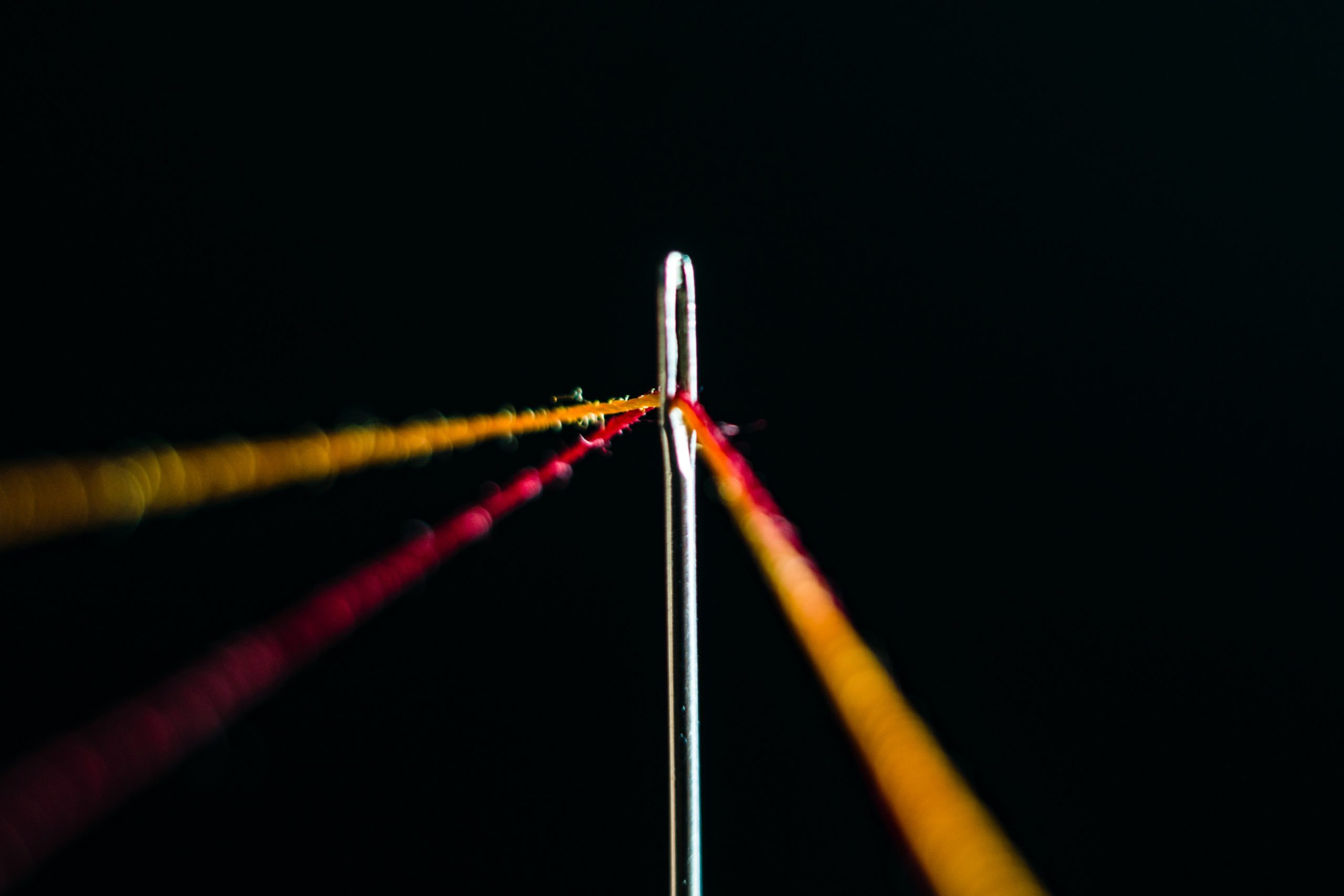

Lo and behold, as a mirror match to their whirlwind romance, within a few months Linda was expecting, and she delivered a healthy baby girl at the beginning of February. They named her Olivia, after Linda’s mother. How wonderful it was to see the ladies of the church fawning over her and piling up the gifts of sleepers, homemade blankets and crafty knickknacks with the baby’s name and birthday painted, embroidered and stamped on them. We may not do music as well as the big Pentecostal church up the highway, but we sure do know how to welcome a little one.

Little Olivia was baptized now two Sundays past, and the service was one like I’d surely never seen before. But the journey to the baptismal font was long and painful, and it is a story that bears retelling.

Of course, soon after Olivia was born, Pastor Morton went to visit with Linda and Danny, and amidst the congratulations and oohing and aahing, he asked them about baptism. They talked over the meaning of baptism, and different dates that would work best for members of their families, and then Linda surprised Pastor Morton with a request he’d never received before. She said they wanted Olivia baptized by immersion. When he told me about it later, Pastor Morton said at first, he thought Linda had her baptism terminology mixed up, what with her being a new Christian and all. But no, it soon was clear to him that she meant what she said: they wanted little Olivia baptized by dunking her completely under the water. Linda explained that after she had come into the church, and she learned about baptism, she was really struck by what it said about the sacrament being not only a sign of cleansing from guilt, but also dying to sin. Because of the symbolism, she wished she had been baptized in our church by immersion. Then, a few months before the baby was born, her cousin told her about attending a service in a church in Saskatchewan, where the baby was dipped under the waters, head to toe! Right then, Linda decided, she wanted her child baptized in the same way.

Well, Pastor Morton said he wasn’t about ready then and there to sign on to dunking a baby in church. Who knows what odd cult her cousin might have stumbled into! He told them he’d give it some thought, do some checking, and talk it over with the elders. Linda and Danny said they understood, as this was not something that the pastor or our church had ever done before.

Over the following days, he checked around and soon discovered that although the practice of infant baptism by immersion was not real common, it certainly was a legitimate practice. It had a long history in some branches of both the Anglican and Eastern Orthodox churches. Through the internet he contacted a priest who performed such baptisms on a regular basis and found out how to do it. It turns out, the trick is to blow quickly into the baby’s face, just before the dunking. The baby is so startled by the blowing that he will gasp; he’ll quickly breathe in and hold his breath for a moment, just long enough to dip him under the water and then quickly lift him out again. The priest said if the water is warm, and your timing is right, it goes very well. If your timing is off, well, then there’s a lot of choking, coughing and screaming. But either way, the deed is done.

Armed with this knowledge, Pastor Morton decided to seek the elders’ go ahead to baptize Olivia via immersion. He explained the reasons why Linda and Danny had made the request, the symbolism they saw so visible in immersion instead of sprinkling, and the matter of technique as explained to him by the priest. He had also already made the arrangements to borrow a brand-new livestock watering trough from the Seed and Feed Store over in Dempsey. Kees and the other elders gave him the green light to go ahead, but they asked him to please try a practice run with Olivia in Linda and Danny’s bathtub.

Well, of course word of the plans for the upcoming baptism soon spread through the church like dandelions across a spring lawn. Pastor Morton had talked to the chair of the Worship Committee about decorating the water trough with greenery or ribbons or some such thing, and of course the elders could hardly wait to tell their wives what was in the works. And that’s when the squabbling started. Reactions to the news ranged from delighted to curious to downright ornery. A number of my friends in the knitting circle told me they thought it was the worst idea they’d ever heard of. Edna Walsh told me I’d better get over to Linda’s and talk her out of it to save the church from the embarrassment of it all, before we were written up in the Gazette in the same section where you read about people’s vegetables that looked like movie stars or that lamb that had been born last spring with six legs.

Now, I have to admit, when Kees first told me what was in the works, I had my doubts as well. But to hear some of the members of the church talk, it was as if Pastor Morton would be doing the baptism dressed as Bozo the clown! What really got my apron in a knot was the way many people didn’t bother to find out the truth of what was planned, and all manner of rumors and wild stories were being circulated. And, because other members thought the immersion baptism was a great idea, the arguments and the fighting broke out all over.

But it was one person in particular who made a crusade of the movement to get Pastor Morton and the elders to change their minds: Henk Blystra. Henk called up the pastor and surprised him with an earful of opinions over the phone, and demanded to meet with the elders to, as he put it, ‘talk some Scriptural sense into them.’ Given the way conversations were spinning out of control in the congregation, Pastor Morton thought it best to give an opportunity for Henk to express his objections. Thus, a special elders’ meeting was called, and Kees and the others made time to come together again to hear him out.

At the meeting, Henk made his case, or perhaps I should say, Henk launched his attack. He said that the plans for baptizing Olivia were not Reformed, because the emphasis in the Heidelberg Catechism is on washing, and no one washes babies by pushing them underwater. He went on to say that baptism by immersion was not Biblical, because the Apostle Paul himself was baptized in someone’s house, back when no one had a bathtub or any other way of completely dunking an adult believer. So, he said, Paul must have been sprinkled, just as real Bible believing Christians are baptized today. He quoted Genesis 18:4: “Let a little water be brought, and then you may all wash your feet and rest under this tree.” He also read John 13:5: Jesus “poured water into a basin and began to wash his disciples’ feet, drying them with the towel that was wrapped around him.” If washing by sprinkling was good enough for Jesus, it ought also be good enough for us, Henk said. He then went on to criticize Linda’s character, and question her faith, suggesting that the elders had been taken in by the foolish request of a baby Christian who was herself, in reality, barely beyond paganism.

Well, of course Kees was fit to be tied. But he wasn’t the first one to speak up. Karl Schneider said that he’d been thinking about their decision too, especially with all the talk going on, and he thought that perhaps the church would be best served by a regular baptism, as he called it. Too many people were getting upset by the decision to dunk the baby. But then Kees lit into him, saying that the gossiping of a few busybodies ought not be listened to by the elders of the church, let alone blessed by their giving in. Of course old Henk didn’t appreciate being called a gossiping busybody, and he started up again. The whole thing apparently got fairly ugly before Pastor Morton put a stop to it by ending the meeting with prayer and sending everyone home to cool their jets for a while.

Neither Kees nor I slept well that night, because of course he told me everything that was said in the meeting as soon as he got home. We knew Linda would be devastated if she knew what was being said about her. She already was upset enough at some of the comments people had made. And that’s when Kees and I talked about leaving the church.

Understand, what I mean is leaving the Annora congregation, not leaving the church as a whole. The conversation’s twists and turns that night surprised us, we’ve been part of that little church for so long. My parents were among the first families to launch the church soon after the wave of immigration after the war. Kees and I were married in the old sanctuary, before we put on the addition. And yet, on top of all the ways we’d been blessed by the Annora church through the years, there were also a whole heap of hurts as well. We’d put up with criticism about some of the ministry we did, there was the teasing that our Andrea underwent from the other kids at the church, and the gossip that went on after our prodigal son Martin disappeared and then later came home. Church can be a wonderful source of blessing when it is healthy, but when church goes bad there’s nothing quite as painful in all the world, I’m sure. How could we stay on in a congregation that didn’t know what it means to be the church to each other?

It was a couple days later that I ran into Henk at the hardware store. I’d been stewing for all that time about the things he’d been saying, not only at the meeting with the elders, but what others had passed on to me. And so right there between the plumbing supplies and the power tools, I let him have it. I told him the church and the kingdom of God would be better off if he minded his own business and started searching the Scriptures for verses to apply in his own life rather than preaching to everyone else. And before he could say a word, I left. It was a bit awkward, because I took a bag of birdseed with me, and the cashier had to chase me down in the parking lot, but I felt I’d made my point.

Right that afternoon we got a call from Jenny, Henk’s wife. She was short and to the point, saying both Kees and I needed to come over and clear the air. It was a bit late by the time Kees got home, but we double checked with the Blystra’s and yes, they still wanted us to come to talk. When we arrived, there was none of the usual niceties, though Janny did serve us tea before telling there was more to this story, and she looked over to Henk, expectantly. He cleared his throat, and his story came tumbling out.

It was right after the war, back in the Netherlands, that he had been left to watch his younger brother Arie, who was only a few months old. His mother had needed to supplement the family income by doing some housekeeping for a wealthy family in a nearby town. Henk’s aunt was supposed to come over to watch him and his brother, but she hadn’t shown up and his mother had little choice but to leave him in charge, though he had only just turned five. His memory of what happened was foggy, but Henk did remember that little Arie started crying, and though he was supposed to leave him in his cradle, Henk picked the baby up and realized that he was wet. Wanting to be a big helper to his mother, he decided to give his brother a bath. He pulled up a chair to the sink, filled it with water from the pump, and put Arie in.

At this point in the telling, Henk stopped speaking, and he buried his face in his hands. Janny started to say something, but Henk cut her short, holding up his hand. He composed himself and continued.

Arie drowned. Henk didn’t even realize it, not until his aunt finally arrived and found them in the kitchen. When his aunt started screaming, he ran and hid in his bed. No one got him out until the next day. And it was right after the funeral, while everyone was eating soup and buns, that the minister’s son, who was a couple years older, told him that his dad had said that Henk was a murderer, and he needed to repent of his sin.

Henk stopped speaking. He sat with his face again in his hands. And Janny said, “Henk has always had trouble with the church, with ministers, and with babies. He could not be around when I would bathe the kids. I had to always do it when he was out in the barn.”

I could not speak. The tears were trickling down my face and into my lap. Kees, however, was not without words. He reached out to Henk. He moved next to Henk on the sofa, reached out and put his hand on his shoulder. He reached out as a fellow sinner, as an elder of the church, and as a brother in Jesus Christ. He put his hand on Henk and recited the words of Isaiah 42: “A bruised reed he will not break, and a smoldering wick he will not snuff out.” Only he recited it in Dutch, from the version they’d both grown up with.

Kees and I did not say much to each other as we drove home. When we went to bed, Kees fell almost immediately to sleep, according to his unique giftedness. I could not sleep. I was a mess of tears and grief and guilt.

The next day, Pastor Morton called and left a message for Kees. Henk was withdrawing his objections to the baptism, and he asked that Kees would explain matters to the elders. In the end it was decided that Olivia would be baptized by immersion, not because it would please the congregation, but because it would please the Lord.

And so, two Sundays back, Olivia was baptized. She responded appropriately to her dying to sin and resurrection to new life, with confusion and wailing. Pastor Morton’s timing may have been just a little bit off. Of course, Henk did not attend that Sunday, but Jenny did. And in the fellowship hall afterwards I watched her as she held Olivia, cooing away at her even as the tears fell on her baptismal gown.

It was a great celebration for we were all reminded that God reaches out and embraces in grace his undeserving and unknowing children. A wide-eyed baby. A young couple in love. An old man haunted by memories. A foolish young preacher’s son. And a repentant old housewife, whom he is trying to teach patience and wisdom.