You stand transfixed, hugging the cork bark of the Baobab tree as warm liquid drips down your legs, staining your white socks yellow. You want to bend down and scratch because it’s itchy, but you are frozen to the playground. You watch them form a circle around you. The revulsion in their frowns and screwed up faces does not match the excitement in their flicking wrists.

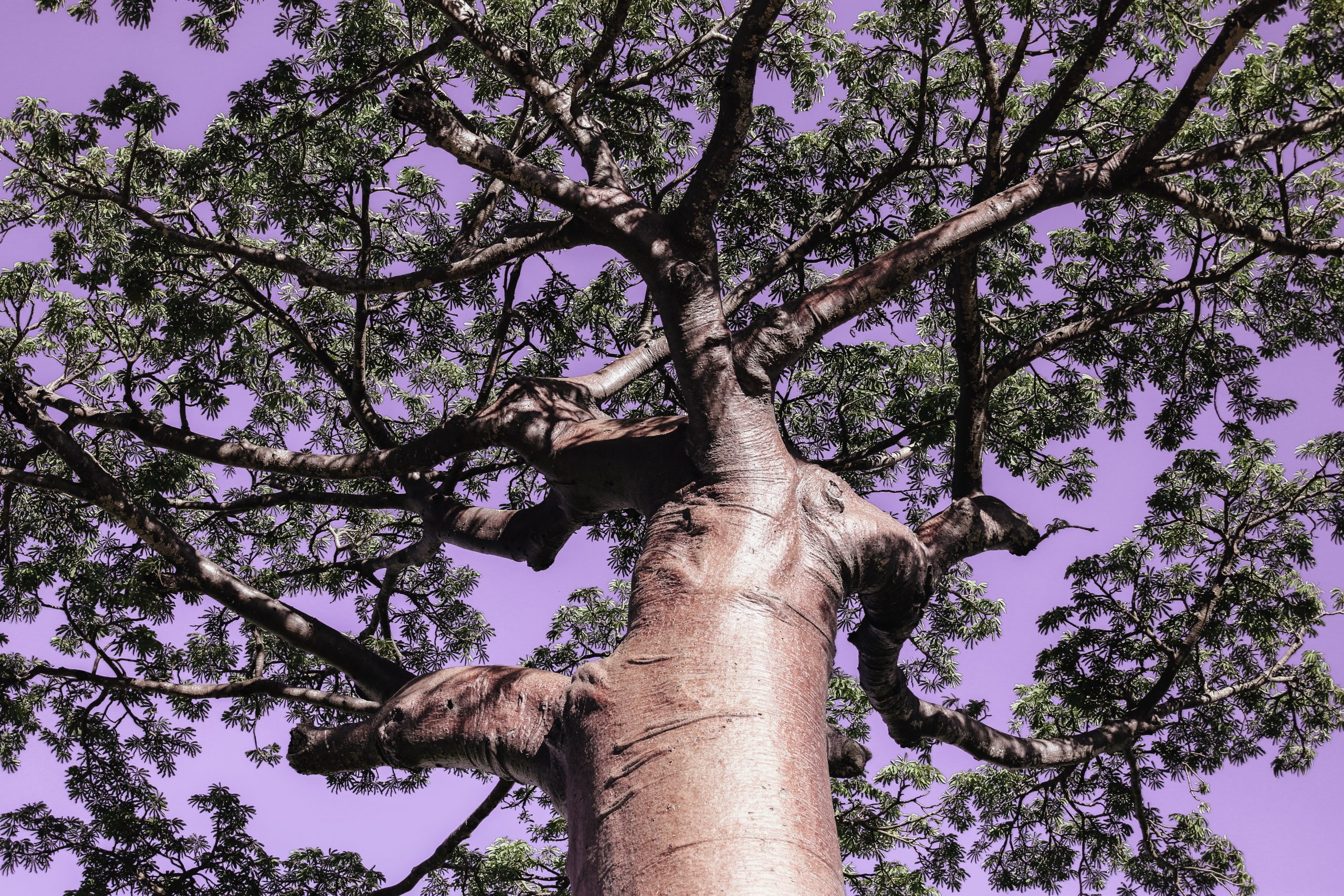

‘She’s wet herself again, Ewwwww,’ shouts one of the girls, pinching her nose shut with her thumb and index finger, disgusted by a smell that has yet to arrive. The children become more animated now. They run in circles around you chanting, ‘Gross’ and ‘Disgusting.’ You have gone. Only your body is left behind. You have this ability to remove yourself from places you want to escape from; a kind of magic trick you have become very good at. When the options are fight or flight, you choose to freeze. You walk through the long corridor of your mind and find a library stocked with all the stories your grandmother told you. You reach for a book and blow the dust off, watching it fly around the dimly-lit room. It’s the story of the Baobab Tree.

Long ago, when the gods were busy crafting shapes out of clay to make the animals, plants and people to fill up the world, they decided it would be fun to add a giant talking tree. At first, everyone in the heavens was delighted with the new tree, nurturing it with gentle rain and warms rays of sunlight. They decided to call it the Baobab tree. Now the Baobab tree talked all day and night, using each of its words to complain. When it whined about the sweltering heat, the gods sent down a cool breeze. But it soon became dissatisfied with the breeze too, saying it was much too cold. When the Baobab tree finally stopped complaining about its surroundings, it then began to moan about its own appearance. It wanted to be taller than the giraffes and prettier than the most beautiful flowers. Soon the gods were so fed up with the talking tree that they came down to earth to try and reason with it. But there was no pleasing the talking tree and so the gods were left with little choice. They pulled it out of the ground, turned it upside down and pushed it back into the ground head first. The tree could no longer say a word with its mouth filled with moist earth.

You feel sorry for the Baobab tree, who had to swallow all of its words, just like you have swallowed yours. Maybe that’s why you hug the tree to your chest. The sound of the school bell, ‘kong go lo lo lo, kongo lolo lolo,’ cuts through the air, bringing you back to the playground. You watch the circles of children turn and run towards the sound. They line up like soldiers outside their respective classrooms, leaving you behind. You feel the muscles in your body thaw and you wiggle your toes in wet socks. You unwrap your hands from the Baobab and squelch back in your black leather buckled shoes. You go to the bathroom to squeeze out the urine from your clothes. You splash some water onto your bottle green skirt and lift it as high as you can up to the hand dryer.

When you get to class, everyone else is already in their seats and you avoid the eyes that follow. The teacher asks why you are late as giggles are muffled by palms throughout the room. The strong stench of urine rises up from your damp clothes and you imagine it snaking around the room, diving into the noses of your classmates and teacher.

Your words stopped and the bedwetting started at the end of Ramadan. That was when your father’s sister, her husband and your two cousins visited from London. They stayed at your grandmother’s house for three weeks. During that time, there were many parties and dinners organised for the extended family to meet your aunt. It was the first time she’d travelled back to Africa since her arranged marriage. With so many bodies in the house, it was easy to lose count of all the running children and chattering adults. Your uncle from London was magnanimous with his gifts and compliments. He fooled them all. But you saw the hardness in his stone eyes before any of them did. Your stomach curdled when he looked in your direction and you tried to make yourself as small as you could.

It happened on the 27th night, the holiest day in the holiest month of the Islamic calendar. It’s called the Night of Power because it’s the very night that people believe the Quran was revealed. If you happen to be praying at the right time on this night, all your sins will be forgiven. All the adults went to the mosque for the special prayers, hoping for redemption. Your uncle said he had a migraine, pressing his temples down with his knuckles to prove how bad it was. He offered to look after the children since he wasn’t well enough to go to the mosque. The adults agreed with sympathetic eyes for the man who bought suitcases full of glossy gifts. You cried to go to the mosque, but your mother said you would get too tired and would be more comfortable at your grandmother’s house with all of your cousins.

You remember the sound of the car tyres leaving the gravel driveway, filling your stomach with black butterflies. You were sleeping on a thin mattress on the floor of the living room when your uncle’s cold hands slid under the blanket. That was the first time you froze. You only remember it felt like there were a thousand tonnes of bricks on you and that you smelt the sourness of his heavy breath. You floated above your body on the thin mattress and saw all the other sleeping children scattered around the living room on their own mattresses. You watched their eyelashes flickering and you remembered your grandmother telling you that the angels kiss the eyelashes of sleeping children. You wondered if the angels noticed that your uncle was there with the sleeping children. You noticed the cream curtain wasn’t closed all the way and you looked out through the window to the dark outside, hoping that someone would see and come in. Nobody came and the darkness crept inside, leaving you feeling lonely and lost.

‘Fahima, are you listening to anything in this class,’ asks your geography teacher. You hadn’t noticed her standing over you, looking down through her glasses with round, magnified eyes.

‘Can’t understand what’s got into you these days. Your body is here, but you are clearly not! What a silly daydreamer you are becoming,’ she says disapprovingly. The class starts to laugh but her icy stare keeps them quiet. You look up at her, wanting to say something, but like the Baobab tree, your mouth is filled with black earth and no sound comes out.