Short Fiction by Lauren Miller

The colonoscopy had been booked a month before the wedding, to ensure matters of the body were taken care of before matters of the heart. But it didn’t matter in the end, both had to be cancelled.

After her still-boyfriend received a text from his specialist, the meticulous plans they’d drawn up for the coming days had to be abandoned. They looked upon the cupboard where they’d already begun to store the things he would need pre-colonoscopy; a litre plastic bottle for the laxative concoction he was to drink, the dry foods and supplements his was to consume while fasting, endless protective products to be used during his extended exposure to the hospital.

It was as if the kinetic energy they’d reserved for the final stretch towards marriage required a new channel, and planning for the colonoscopy had been a great distraction. But now it seemed they were destined to combust in the microcosm of their flat, from the unrealised potential of the coming few months and their oncoming lives.

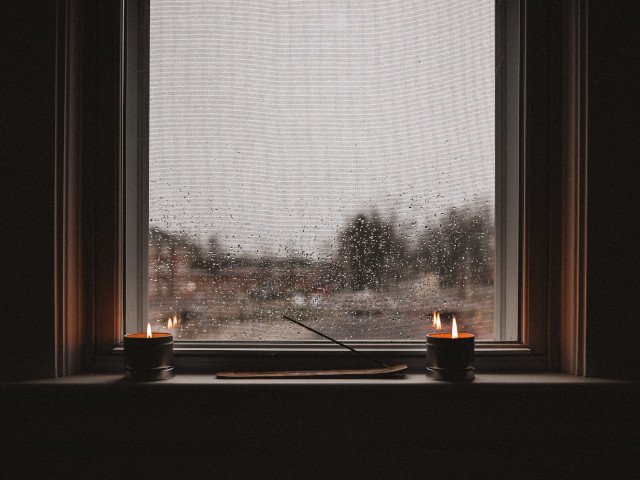

She took to cleaning the windows with washing up liquid and vinegar. He took to his bed, not unlike how he’d planned to spend his post-colonoscopy days anyway. They watched television, interrupted by the thud of bumblebees and other insects that flew into their own reflections, hitting the crystalline glass then falling dead on the windowsill.

*

He’d told her of his illness early on in their relationship. She’d always known there was something different about him. He was a careful man with an eye for detail, troubled by slight injustices that were beyond his control. He decanted medication into pillboxes the way her grandparents once did. He abstained from alcohol and didn’t eat the seeds or skins of fruit. Just being near him gave her sense of order she’d never known possible.

Dating a sick man made her feel important for the first time in her life. Not from the sense of duty to keep him healthy, she never signed up to all that. But because she was from the kind of family where illness and death, disease and despair were the penance you paid for being taken seriously. She was always a healthy, robust child and grew into a healthy, robust woman, which meant she was often belittled by them.

They’d been dating six months when one time he asked if she could pick him up from the hospital. They’d booked a holiday and she insisted they leave as soon as his appointment had finished. He agreed, said he should be fine. She hoped he’d think her urgency was merely stress from being overworked, or an eagerness to spend time with him, not a stone-dead selfishness she would carry with her always. She carried both their suitcases to the hospital and headed to the ward to find him.

When she got there, he was stood up in the waiting area, woozy from sedation and rubbing his eyes. She gave the nurse a smile and a nod like they shared a private joke (the joke where: genetics is a lottery and the winners can only appreciate their luck in the presence of those who lose out) and slipped her arm around his waist and walked him out into the sunshine.

A stoner-grin lolled across his face as she led him through the streets to the train station. He was coherent but spent long stretches of the journey not saying anything at all, just blinking back the brightness of the day. At the station, she looked over the timetables and tried to find their platform. When she turned around, he was gone. Left again with the suitcases, she dragged them to the ticket office where she’d just paid for their tickets and made a mental note that he’d better buy her dinner later. But he wasn’t there. She imagined this was how mothers felt when they lost their children in supermarkets, the distress made almost bearable by how stupidly cliche the situation was.

She found him in a cafe waiting in line for a sandwich. She’d been angry but again, like a mother must feel when their lost child is found, she couldn’t convey the poignancy of her relief and her rage, so expressed neither. She was irritable the rest of the journey, as she slowly realised she’d never be able to communicate the depth of her love for him, or her fear.

*

They stayed inside and watched the purple sky, counted the animals that collected along their windowsill. They’d had some conservative plans to celebrate after the colonoscopy, ordering takeaway, buying reduced Easter eggs, watching his favourite movies. But it didn’t seem fair to allow themselves the reward without his purging and prostrating. They had to be strict with themselves, self-control was important in these unprecedented times.

She was secretly glad she didn’t have to watch one of his movies. He was far older than her, and although their tastes overlapped there was a blind spot when it came to cinema. He was shocked at the obscure thrillers and spy films she’d never seen but could vaguely recall the covers of in the VHS store of her childhood. He thought her taste in film veered too much towards the debasement and physical violence inflicted upon others.

Soon they started to pull some of the bigger bodies inside. The windowsill began to weigh from the weight of them. They lay the animals upon the carpet. They stroked the colourful feathers of the birds with broken necks, wondered if they too would soon be allowed to live a life that allowed for the rough with the smooth, instead of these frictionless days, these perpetual lazy afternoons, expecting and wanting for nothing.