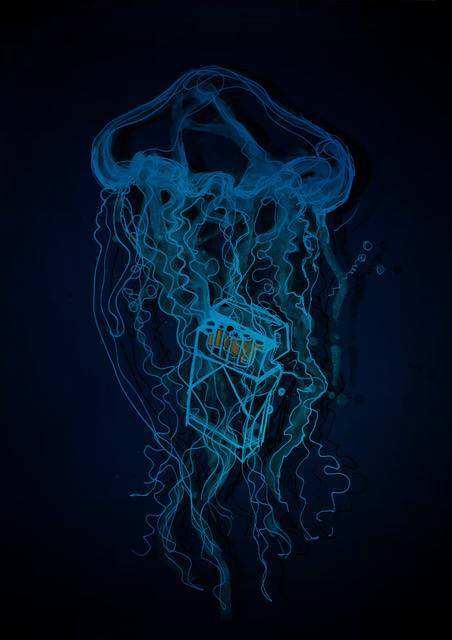

Whistling, I gaze through my reflection. This plexiglass doesn’t look strong enough to hold all that water. After a moment, it seems as if a smack of moon jellies are floating within me, and I have a stomach full of UV berets. Even so, I admire the glass. Framed by an ever-changing light feature; the flat strength of it is remarkable. The moon jellies turning pink, yellow, green and blue as the light changes the abyss.

Mum nicknamed me Jellyfish because I was brainless like one. It’s her birthday today. Though I always remember it, I never acknowledge it. But I’m thirty and she was thirty when she passed, so I have a colin the caterpillar cake and a tea-light in my bag.

In the centre of the moon jellies’ translucent bellies are four luminous horseshoes (gonads, I know), stark against the navy-blue water. That’s how they reproduce.

Except I can’t see any babies. In a cluster by the glass, the grown-up ones move like the opening and closing of an umbrella. I wonder what rain feels like when you are deep inside water. Is it a thing?

A sign on the tank reads: Did you know jellyfish are silent? They do not communicate. Just float around and feed.

I sit down on a wooden bench, my rucksack on my back. I put my hand in my pocket to check the piece of folded paper is inside.

The pink light fades and the water swirls with diamond flickers of light. Staring at the haunting gloam of the jellyfish, I go to my childhood. Thinking of it – hunger, slaps and too many sweets – my nickname is apt. There they are. Those darling council flat years spent being told to shut up and go away.

*

“Please, if there is a God, let there be a Colin the Caterpillar cake,” I prayed before running into the kitchen.

It was my tenth birthday, and I could barely see through the smoke. I heard the vicious growl of Lola (pronounced LOO then LA) and I coughed. Mum, her sisters, her friends – everyone was hers – were sat around the table. Mum tutted and her eyes rolled into the back of her head. What did she see when they turned back there? I wanted to climb on board her eyeballs. Like a voyage to the far side of the Moon, and plant a flag that read ‘Remember to buy Sonata a Colin the Caterpillar cake on her birthday’.

“Go play,” Mum barked. “This is grown-up talk.”

There were no seats free, so I jumped onto the side cabinet and perched in the corner by the sink. It was piled high with Sports Direct mugs and dried jam-stained plates.

“Oh no,” I said.

My bum was wet. I hadn’t noticed the slippery wet surface, clear and deceiving.

“Shut up!” Mum said. “Can’t you see we’re talking?”

“I sat in something.”

“Go away!” Mum shouted.

If an alien watched our flat, it may have thought my actual name was Go Away. For a long time, I thought it might be my secret name. I even wrote it on my name tag at school.

I jumped down from the side and walked away, pulling my t-shirt over my bottom.

“Passive smoke is bad for you,” said Aunt Hilda, her voice splintered like unsanded wood.

In the hallway, I paused. There was an outline of a person at the front door. They were small like me. The handle turned downwards and swung open. It was Cousin Reenie. She was wearing a pink dress with a little white shrug tied under her flat chest. Her hair was in two blonde braids and a plastic pink handbag was tucked under her arm. She looked older than eleven. That’s why she was picked to play Mary in the school nativity, and I was Sheep Number Thirty-Two. I moved out of Reenie’s way.

“There she is,” Mum said. “Our beautiful little Mary.”

Mum dropped her cigarette into her mug, slapped her thighs and stood up. When Reenie got close, Mum wrapped her arms around her.

“Your hair smells gorgeous,” Mum said.

Hanging over the door was our lucky horseshoe, yet what I saw underneath it, through the door frame, made me feel rusty.

“How come Rennie can stay and I can’t?” I asked.

There was silence. Mum looked at Hilda, Hilda looked at Lola and Lola looked at Beverley.

“How come Rennie can stay and I can’t?” Mum said in a whiny voice.

Everyone agreed that that was funny, but they didn’t laugh they cackled. Everything looked yellow, except for Reenie. She was the pink tongue inside the cancerous mouth.

“Don’t forget the dishes,” Mum shouted. “This isn’t a hotel!”

The kitchen seemed to shake and laugh. Oh gosh, I thought, am I whiny? I’d heard whiny characters in cartoons and disliked them. I used to wish Angelica from the Rugrats off the screen. Maybe that’s why everyone wished me away. I was one of the whiny ones.

Hiding in my wardrobe, I pretended my clothes, falling all around me, were my friends. Yes, I talked to my trousers and, yes, I ignored my one dress. What was I doing wrong? Why was I soooooo rubbish at being human? And (most importantly) how could I be better? The feel of fabric touching my skin was really comforting, like I was an egg in water. I was being held by hundreds and thousands of particles that supported me. I started to sing Happy Birthday to myself. But stopped. My voice was disgusting. I held my throat, aiming to rip my whiny voice box out.

“Hello…” I said in a low voice. “My name is…” in a squeaky voice. “Alright, I’m…” in a voice like a fish. “Yo yo yo, I’m–” in a high-pitched tone.

I stopped when I heard a light click. Opening the wardrobe door, I peeked out.

“Why are you so weird?” said Reenie.

My room was dark; I never opened the curtains. Darkness was a blanket den, keeping my secrets. Rennie, with a halo of light behind her, looked at my bed. The duvet without a cover, the yellow and caseless pillows.

“Go away,” I said.

I twiddled my thumbs around each other. Reenie was like the Sun, too bright and marvellous for me to look at.

“I’ve got a spare lampshade at home,” she said. “It’s a princess one, I’m not sure if you like–”

“I like princesses,” I said quickly.

There was a light bulb dangling from a wire in the ceiling. Spread around it were my WWF wrestling stickers.

“Which princesses?” I asked.

Reenie smiled and ran towards me. She grabbed my hands and span me around.

“There’s pink, yellow, green and blue,” she said.

“There’s a green princess?” I asked.

Reenie, with her eyes wide and her lips pursed, nodded her head.

“I’ll bring it round next time,” she said.

When she left, I jumped a million times. A jump, for how many times better my life would be with the princess lampshade. I thought about Reenie. Her kindness and how the adults liked her company. I should be more like Reenie. It was an excellent idea. I wasn’t a jellyfish; I was a leech (they have thirty-two brains, I know). I clicked my nails between my teeth, loving the enamel ping.

The next day I knocked on Mum’s bedroom door.

“Go away!” she said.

There was a thump on the other side.

“I need to ask you something,” I replied.

“I said, GO! AWAY!”

My stomach gurgled and the hallway started to spin. I chewed. I heard models chewed gum to trick their brain into thinking they were eating, but without gum I used air. When my stomach stopped, I opened the door. Mum was lying down with cucumber slices over her eyes and a half-smoked cigarette in her hand. I trod on a shiny, red stiletto. The thump must have been shiny. Mum’s room was bright, her curtain rail had fallen down and light split in holy beams through the net curtains.

“When is Reenie coming back?”

“Make me a cup of tea would you, hun?”

“I’m hungry.”

“You’re always bloody hungry.”

Mum swung her arm out and patted the surface of her bedside cabinet.

“Here,” she said, handing me a ten-pound note. “Go get me a pack of fags. Get yourself

something nice.”

In my room, I picked up the folded note.

Please let Jellyfish buy the cigarettes

I am very sick and

can’t leave the house and as you know

I am a single mother with no one else to help.

Mum had lovely handwriting. A ballet of letters; they swirled like tentacles in water, joining each other harmoniously. I wanted her hand to have and to hold. I didn’t mind buying the cigarettes. Mr Himla was friendly, and he always gave me a warm croissant. If I bought the cheapest smokes, I had enough change to get a big bag full of penny sweets. Foam prawns and bananas for breakfast. Milk bottles for lunch and chocolate jazzles for dinner.

Walking back from the shop, I had to dodge all the bikes, prams and picnic baskets. Everyone was on their way to the pretty park. That marvellous stretch of land with grass, swings and a stream trickling through the middle. Standing on the crusty green railings, I stared at the seesaw. It squeaked up and down. Two children sat at each end. They were wearing dresses. I giggled noticing that one was flashing her white knickers. In the middle, with her legs dangling either side, was Cousin Reenie.

Wow, I thought. She has friends. If I wanted to be more like Cousin Reenie, I’d have to start wearing pink and get rid of my oversized khaki combats and Fruit of the Loom t-shirt. Reenie and her friends sprinted towards the roundabout.

I guess if I wanted to lose weight, I’d have to stop eating sweets. After I finished the ones I had, I’d begin. Chewing chewing gum, chewing air.

Both girls span Cousin Reenie on the roundabout.

“Faster, faster!” She squealed.

She sounded like Mum’s handwriting: elegant and tiny. If I was going to be more like Reenie, I had to change my voice.

Three days later, Mum and I were in Peacocks. She had got some tax back and decided to treat herself. On our way to the dressing room, Mum stopped. I was struggling to see over her piled up sequin dresses. We were at the edge of the children’s section. Little polka dot dresses displayed in size order. Smallest at the front, biggest at the back. Mum pointed to a small, fluffy orange top and looked at me.

“I wish you’d wear clothes like this,” she said.

My arms were numb.

“Mum, I can’t see. These are heavy.”

A little girl walked over. She was wearing a lilac dress, with so many bows a Christmas present must have puked on her. She picked up a polka dot dress from the front part of the rail. She walked off like a poodle, wagging her bum.

“She looks lovely,” Mum said. “Like a proper little girl.”

On the wall was a long rectangular mirror. I could just about see my chubby face and the mousy blonde hair falling in uneven layers around it. A stupid haircut I didn’t want but had to have, because Mum insisted that it looked like Rachel from her favourite program, Friends. I knew it wasn’t Rachel’s hair that made her beautiful.

“I don’t like those clothes,” I replied.

Mum shrugged and flung the orange top onto the pile. My arms trembled. I held my breath.

“You should hold your stomach in,” she said, patting her stomach. “Eventually it just stays

in.”

The sequined clothes dropped on the dressing room floor.

Two weeks later, I asked Mum if I could borrow her belt to keep my trousers up. Her eyes lit up like candles. That night she cooked a special dinner. Potato waffles, beans and dinosaur-shaped chicken. With it on our laps, we watched Brookside. During the adverts a man with white hair, sang always look on the bright side of life. Mum started whistling. I tried to join in but could only manage some puffs of air and dribble.

“Love you, Mum,” I said with chicken on my tongue.

“Don’t eat with your mouth full,” she said with chicken on her tongue.

We both laughed and a bit of wet liquid shot out of my nose. I used my hand to wipe it away. Two ladies were sniffing white towels. I recognized them from a program Mum liked called Birds of a Feather.

“What did you want to be when you were my age?”

Mum looked at me. She tilted her head and put her hand on my knee.

“A wife and a mother. Ridiculous I know but–”

The doorbell rang.

“Get that Jellyfish,” Mum said.

It was Cousin Reenie and Aunt Hilda.

“Where’s my lampshade?” I asked.

Reenie looked at Hilda. Hilda looked at Reenie.

“Who is it?” Mum shouted. “If it’s Avon tell them to go–”

Hilda grabbed Reenie’s hand and barged past me. I closed the front door. A pile of post had gathered on our doormat. Long thin menus advertising various takeaways, little window cleaning business cards and bills in unopened white envelopes. My shoeprints were on the post. I could see the angular design. The impression I left from the pattern of my sole.

I ran into the living room. Reenie had my dinner on her lap, chewing my last chicken dinosaur. Mum’s mouth was wide open, and Hilda had her arms crossed over her large breasts. She was shaking her head. I sat down on the arm of Mum’s chair. The second half of Brookside was about to start, but I couldn’t hear anything.

“Where’s the remote?” I said.

“So rude,” Mum snapped. “Go to your room!”

Reenie, with my last dinosaur in her hand, started crying.

“She told me to give her my princess lampshade otherwise…”

My face flamed. I remembered Reenie whirling me around my bedroom offering and

promising me stuff. I swallowed but my dry mouth tasted wrong and disgusting.

“I didn’t. You offered it to me.”

A smile flashed across Reenie’s face. She shoved the dinosaur in her mouth.

“Give me back my dinner!”

Like a jockey on a racing horse, Reenie quickly chewed my food. I felt my skin transform into glass. My body filled with a rapid of water. Reenie swallowed and stuck out her tongue. Her pink tongue was empty. My glassy body shattered.

“BITCH!” I screamed, before rushing out the door.

Reenie had ruined everything. Instead of my stomach rumbling, it bubbled. Was this how an engine feels when it starts to drive? Key in ignition and BAM power. That’s how I felt stomping up the hallway, like a driver. Until my Mum’s footsteps sounded behind me. I sprinted into the bathroom and locked the door. Mum kicked the door. I said sorry a thousand times. A sorry for how many more times worse my life would be now I’d said bitch to Reenie. I pressed the heel of my palms into my eyes, trying to stop myself from crying.

“Get out here now you little shit!” she shouted.

I turned the faucet on to pretend I was showering. Trying to remember those golden moments before the bell rang and changed everything, I started whistling. Mum stopped banging.

“We best be off,” I heard Hilda say on the other side of the door.

“Why did you eat her dinner?” I heard Mum say.

“What?” Reenie giggled.

“You heard me you little bitch, why did you eat her dinner?”

My ear was on the door. I was washed over by a surreal sensation. My skin didn’t feel like glass or water or anything.

“Don’t you ever speak to my little Ree Ree like that again,” Hilda said.

“Get out!”

“She’s gone mad,” Reenie said.

“Get out of my house! Now.”

I heard the front door slam. Silence. I got up and turned the tap off. Out of habit, like I’d not heard anything and was doing a big pooh, I flushed the toilet.

“Sonata?”

I opened the door. Mum was sat on the floor. She looked up at me. Grey streams of mascara on her cheeks.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I’m so, so sorry.”

She tumbled forward into an aggressive amount of wailing. I sat down next to her and hugged her. My arms couldn’t hold her tight enough.

*

A few weeks later Mum killed herself. I searched the flat for a note. But all I found were empty cigarette packets and that folded piece of paper I always took to the shop.

*

The sound of crying brings the aquarium back into focus. The moon jellies are clustered in the corner of the tank. They all look the same. The lighting changes from red to white. Their luminescence looks like an ultrasound. I taste smoke in the back of my throat. Mum used to be my aquarium. Now I am hers. She lives inside me. All those moments we never had play, on repeat. I unbuckle my bag. The crying becomes louder. I look towards the archway, there is a little girl. Her forehead furrows. She is wearing jeans, high top trainers and a blue sweat band around her wrist. Her baseball cap is on backwards. Her short hair flicks through the adjustable strap hole. Her sockets squelch as she rubs her eyes.

“Don’t do that,” I say. “You’ll make it worse.”

She whimpers.

“Do you have water in your backpack?”

She nods.

“Can you get it out and drink some? It will make you feel better. Like an aquarium in your

belly.”

The little girl smiles and quickly unzips her bag. When the gulping stops, she sighs.

“I can’t find my mummy,” she says.

In the tank behind her, the Moon Jellies disperse. The long sheaths of seaweed, sway

in a watery breeze.

“We were walking to see the octopuses. Mummy wasn’t holding my hand because she wants me to be independent, but a big group came in and–”

The little girl looks constipated.

“Do you need the toilet?” I ask.

Her bottom lip wobbles and she starts crying again.

“Don’t cry. There’s enough water as it is.”

The little girl drinks. There is another sign.

Did you know jellyfish are bad parents? Once they give birth to their planula, they just leave them. Providing no further care.

“Are you on your own?” the little girl asks.

The water bottle has made a red suction mark around her mouth.

“How old are you?” I ask.

“Ten.”

“If you wait here, I’m sure she’ll find you. Or we can go to the desk? Get the assistant to make an announcement?”

The little girl sits down on the bench. She looks at the tank.

“It’s funny when you go to a tank and you can’t see the creatures you came to see. It happens at the zoo, too. You have to really look to find them. Especially reptiles. It’s fun if you find them. But not so fun if you don’t.”

“I’m looking for my mum too,” I say.

The little girl’s eyes narrow. She looks at the tank.

“They look dead,” she says.

I reach into my bag. I pick up the cake.

“Like ghosts.” She gasps. “Do jellyfish have ghosts?”

My stomach lurches. I scrunch my brows. I’m not sure what she means by ghosts, there are

so many ways a dead thing can still be here, haunting. I see Mum. I hear my nickname; Jellyfish and feel the rush of all the broken things I couldn’t fix. I leave the cake in my bag but keep my hands inside. Phantosmiacly, I can still taste the smoky odor of when I tried to kiss her back to life.

Tears well up in my eyes. I nod.

“A Jellyfish has to make peace with their ghosts. Then they go away.”

Her mouth pulls downwards by the muscles of her pain.

“Mummy!” she says, suddenly remembering what she’s lost.

I offer her my hand. I want to say don’t cry but I can’t. Not now. I can’t tell her not to do

something.