What makes a compelling folk monster? In many of the great films of that genre, the monstrous is human – a witchfinder who uses his power capriciously to torture innocent women, the conspiring inhabitants of an island ignored by the authorities and hostile to them. In others, the monsters are something natural, seemingly benign – in Andrew Michael Hurley’s 2019 novel, ‘Starve Acre’, the creature is a wild hare. Here, I’m revisiting the story of Jenny Greenteeth, a river-spirit, folk warning, and Victorian anti-heroine

For the last two years, I’ve been researching Jenny Greenteeth, the legend from the industrial north. I first encountered her in Terry Pratchett’s novel, The Wee Free Men. There, she is a minor character, a water spirit, the embodiment of people’s fears. The protagonist, Tiffany, defeats her by striking her with an iron pan. In Molly O’Neill’s children’s story Greenteeth, published earlier this year, Jenny Greenteeth may be monstrous, but she is also a philanthropist dedicated to protecting the human. The story domesticates and tames Jenny for a younger audience, surrounds her with stories from other legends – King Arthur, Goethe’s Erlking.

Fifty years ago, Jenny Greenteeth was briefly re-imagined as a man. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents produced a film, ‘The Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water’. A version of Jenny voiced by Donald Pleasance takes pleasure from young children risking their own lives: “That pool is deep, the boy is showing off.” Pleasance, who is both Jenny and Death, warns children to avoid abandoned water, slippery banks and rotten branches.

In an earlier age, Jenny belonged to specific places: the mill dam at Moston in Lancashire, Shooter’s Brook in urban Manchester. Wherever water was dark and threatening, passers-by inhabited the hazard with claims that they’d seen her.

She is easier to locate in a geographical setting than in chronological history. Her first appearance in print came as long ago as the 1820s, when she was a minor character in a play set in Liverpool. Lord Sandon encounters a fishmonger, Etty Greenteeth (“the Phantom of the Cabbage Stall”). He kisses her, she demands to be called Lady Sandon. Over the following decades, Jenny would move north from Liverpool and comedy for horror.

Her reputation grew; sisters and cousins were associated with her. Mid-nineteenth-century sources speak of a family of water creatures: not Jenny alone but also “Peg Powler” and “the Grindylow”. Jenny’s name could be heard in many parts of industrial England, across Lancashire and Cheshire, in towns where industry was growing. “A sore terror,” she was, said an 1850 source, “to rambling children.”[1] According to another memoir from 1852, “Many an old country dame, when nursing a boisterous fretful child or grandchild, has endeavoured to frighten it into quietness or obedience by repeating loudly, with a somewhat mysterious and vacant look, some such phrase as ‘Will wit’ whisp, Jack weet lanturn, un Peg weet iron teeth.’” She and her river-dwelling cousins had become the duckweed growing on abandoned ponds, a warning to the thoughtless that water might kill.

“Some lurk[ed] in the streams and pools, like ‘Green-Teeth,’ and ‘Jenny Long Arms,’” an 1857 narrative records, “waiting, with skinny claws and secret dart, for an opportunity to clutch the unwary wanderer upon the bank into the water.” Jenny had acquired all the physical signs which marked her as a monster, sharpened nails, green hair, outsized teeth. The curious she either drowned or (according to a source from 1876) she “devour[ed]” them whole.

After 1900, the sightings of Jenny were reduced. As the rule of Queen Victoria wore, society grew successively more conscious of industrial pollution, more eager for legislative measures to be taken against it. The Poor Law Commissioners published a Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Classes of Great Britain in 1842; one of its central messages was that fast-moving water might flush sewage and slops out of the great cities. Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Acts passed through Parliament in 1846, 1848 and 1863. Local authorities were empowered to deal with nuisances including foul ditches and cesspools. The Public Health Act 1875 gave local authorities new powers to impose standards on streets and buildings. A rivers inspectorate was established the year afterwards to limit pollution. By the end of the century, Victorians could tell themselves that the problems of waste and pollution had been satisfactorily resolved. Inspectors and local politicians would solve the problem of neglected water; would turn Jenny Greenteeth into a distant memory.

If hazards have returned since then, that has been the work of new generations of politicians, for whom regulation has been a greater threat than neglected land. Danger of Death we paint on sewage pipes these days; the pollution escapes without hindrance, the companies responsible for realising toxins make their killing.

Jenny was on the side of life, not death. She was the kin, in the sphere of popular legend, to Frankenstein’s monster who saves a woman from destruction, refuses to retaliate when a man strikes him, demands a companion from his creator insisting that he if he was left alone with another being he’d thrive. Jenny threatens to kill the unwary person exploring a watery landscape; she does so not in the hope of causing death but to keep us safe.

Jenny has changed several times in her existence. Sighted first to make a laughing-stock of one Liverpudlian aristocrat, she became not long afterwards the custodian of a genuine threat. Then, piece by piece, she was diminished – her harm reduced by successive measures to reduce pollution and make industrial waterworks safe. More recently still, she has been separated even from her liquid context, become almost kitsch. As a character in books, she is once more to be laughed at or to be loved but never to be feared.

The spirit of industrial places, of children’s exuberance, of parental fear, Jenny Greenteeth is not invoked as a living threat. And yet, we still have hazards, are worse equipped to deal with them than were our ancestors of a century ago. Maybe, like the people who would inhabit the areas of highland Scotland into which wolves which are always on the verge of being reintroduced, we would all be happier if Jenny returned?.

________________

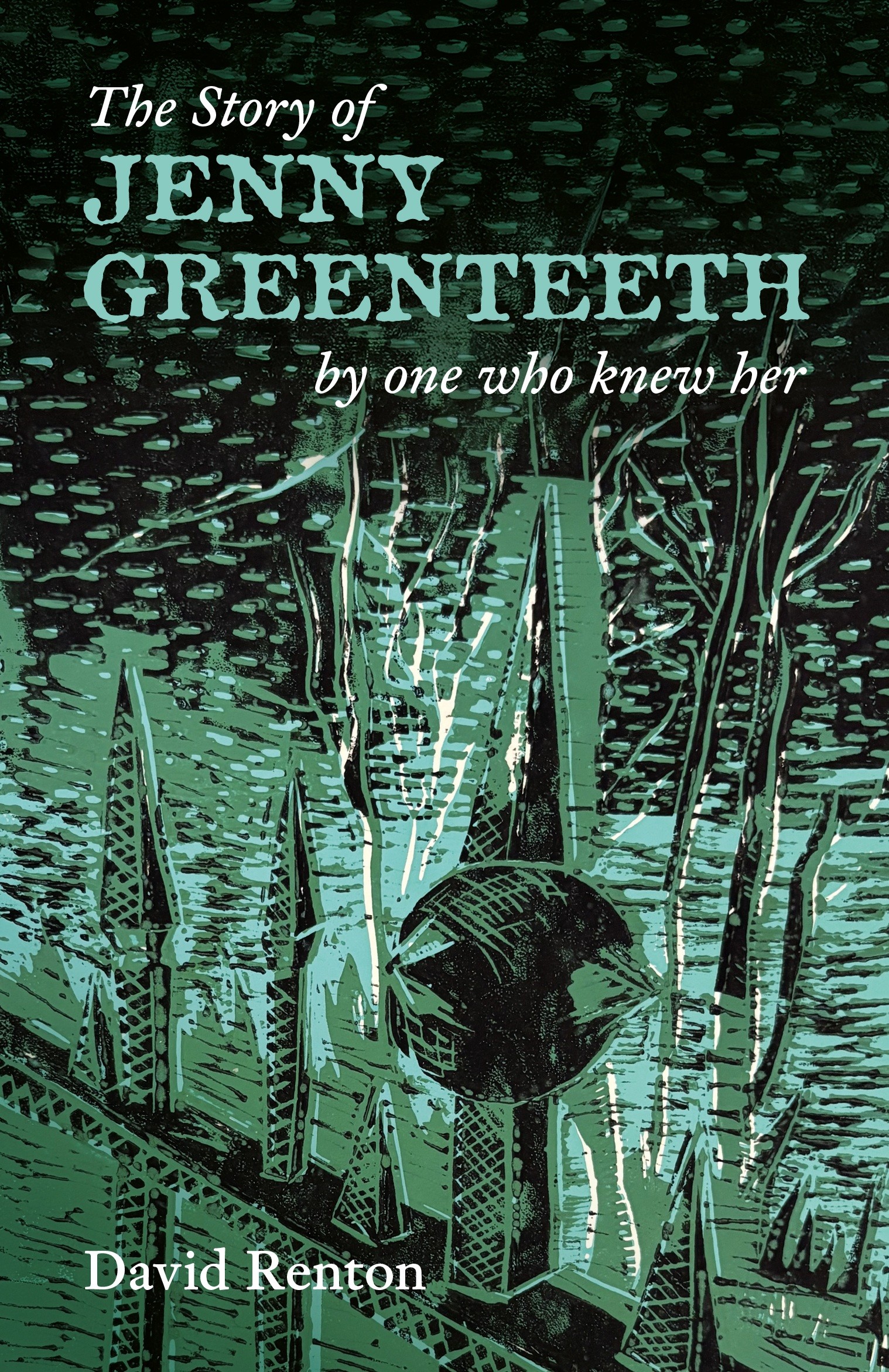

DK Renton recently received an MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck, University of London. His novel, The Story of Jenny Greenteeth, By One Who Knew Her, is published by Hegemon Press in August 2025.

[1] The nineteenth century sources cited here are taken from Young, Simon (6 September 2019). ‘Folklore Pamphlet: The Sources for Jenny Greenteeth and Other English Freshwater Fairies, 2nd edn’. Academia.edu. Downloaded 29 April 2024.