The Intentionality Behind the Work: An Interview with Christopher Paolini

By Akshay Gajria

Eragon, the first book in the Inheritance Cycle, which established the World of Eragon as we know it now, holds a special place in my heart and my bookshelf. It is the second book I’d ever read in its entirety and where my love for books and stories started. I was around 7-years-old and it left a mark. Fantasy remains my preferred genre of exploration and I’m forever grateful to Christopher Paolini for penning the entire Eragon series.

In 2023, Christopher returned to the World of Eragon with his latest book Murtagh. After reading that, and having attempted writing fantasy of my own, I had several questions about the book, magic systems and his writing process. So, of course, when I got a chance to interview him, I jumped at it.

Christopher Poalini is the author of the Inheritance Cycle (Eragon, Eldest, Brisingr, Inheritance) and creator of the World of Eragon and Fractalverse (To Sleep in a Sea of Stars and Fractal Noise). He holds a Guinness World Record for youngest author of a bestselling series.

This interview is divided into four sections:

Writing Process

A Little Bit of Magic

Book Lore

Book/Film Recommendations

Writing Process

AG: Can you walk us through your typical writing process, from idea conception to finished manuscript?

CP: I could talk about this for a couple hours, if I were really delving into the nitty-gritty, but a sort of a broad overview would be: I get an idea. The idea could come from anywhere. Most of my story ideas tend to involve an image or a scene associated with a strong emotion and it is usually either the beginning of the story or the end of one.

Often it’s the end, which is helpful because it’s difficult to write a book if you don’t know where you’re going. In fact, I refuse to write a book if I don’t know what I’m shooting for for the final scene because if I know what that final scene is or at least what the culmination of the story is, then I can tailor everything leading up to that moment to serve that moment. Whatever that idea is.

Assuming the idea is something that engages my passion and interest, I start developing the characters and the story. This happens concurrently. In the past, this involved a lot of worldbuilding for the World of Eragon or the Fractalverse but now that I’ve created both of those settings, I don’t have to do as much worldbuilding, if much at all. If I’m creating a new setting then I would concentrate first and foremost on how this new setting differs from the real world, specifically with physics, whether that means magic which involves physics or science technology. That will determine what is and isn’t possible in the story from travel times to warfare to politics.

This process could be anywhere from two weeks to two months to longer. But assuming it’s a setting I’m relatively familiar with, like in Murtagh I had the story nailed down in about two weeks fairly solidly. So once I have a good idea of the plot and the characters then I’m ready to write. At that point, it’s just a matter of consistency, patience, persistence. Putting in the hours — assuming I have a good solid outline. Then the writing usually goes fairly quickly. I’ll average about one to three thousand words a day, give or take. At that rate, the first draft of Murtagh took me about three and a half months and that was with Christmas and New Year and a couple of birthdays thrown in there. Not too bad. And that’s pretty much how I tackle it.

Those that would be sort of the broad overview of how I would go about writing a book. The older I’ve gotten the more of these I’ve done the more willing I’ve become to put in a lot more prep work in each book just because it saves me a bunch of time down the road.

AG: Is there any book in the Inheritance Cycle that you did not have an outline for and you just wrote?

CP: No, because I had tried writing stories without outlines before Eragon and I never got past the first five or ten pages because all I had was the inciting incident. Before writing Eragon, I actually plotted out an entire fantasy book and created an entire world for it just as an exercise to see if I could plot out a story. I never wrote that book or story. I just shelved it. (Maybe I should go back to it someday.)

When I decided I was gonna plot out an entire trilogy, I wrote the first book as a practice novel. Just to see if I could and that ended up being the Inheritance Cycle. So even before I wrote Eragon, I had the broad framework of the entire series and I can prove that: If you go back and reread Eragon after he drags his uncle to Carvahall, he has a night of bad fever dreams after that and one of those dreams directly describes the very last scene in inheritance.

Now, the novel that I did attempt to write without a really strong outline was To Sleep in a Sea of Stars. And that’s the reason it took me so many years to write and revise it. I personally cannot plot and write at the same time.

AG: That gives me a very good idea of what your writing process looks like and I’m so glad you touched on To Sleep in a Sea of Stars because in the acknowledgments you state how your sister who read the first draft said that you need to rewrite a bunch of it. I always wondered if the success of Inheritance Cycle changed your writing process or did that make you a lot more conscious about what you are about to write?

CP: Ultimately, it made me more conscious knowing that I have an audience. Knowing that it’s my career and not just a hobby. And also just wanting to be good at it.

AG: Has your writing process evolved because of how well received Inheritance is or do you still stick to the same bones?

CP: Well, it become more structured. The way I approach each story is a lot more organised and I try to be a lot more organised with my thoughts, my intentions. I suppose that’s a good word. Intention. There’s a lot more intentionality behind everything I do because this is my life. This is my career and that’s important to me and I want to write good books. So you’re never gonna go wrong by putting more thought into a book.

AG: That’s a good way of putting it. Intentionality. All of your books since To Sleep in a Sea of Stars are a lot more structured and I noticed this vividly when I was reading Murtagh and also Fractal Noise. I wondered why the initial four books of Inheritance Cycle were not as heavily structured or maybe this was an indication of your growth as a writer?

CP: Now it’s funny, you mentioned that because the first draft of Eragon, or one of the couple of the first drafts actually, had no chapters. I wrote the entire book without a chapter, without chapter breaks because I wanted to provide readers with no excuse to stop. But of course the flip side is that short exciting chapters with little cliffhangers do a wonderful job of pulling people through a story. Thriller writers have known this for ages.

The Inheritance Cycle is very classically formatted. I won’t say structured just formatted, with chapter titles and book titles. There is sometimes a little section breaks when you switch point of views, although later on, I rarely switched point of view within the same chapter, usually one chapter for Eragon, one for Roran.

With To Sleep in a Sea of Stars, I wanted to shake things up. I had read The Dark Tower series by Stephen King and he uses a lot of the formatting tricks that I used in To Sleep in the Sea of Stars, which I liked. Now, with Murtagh, I dialled it back a little from the science fiction. It’s not as heavily formatted. It has has a lot more section breaks though, which I didn’t do in The Inheritance Cycle. Part of that was to just give me an opportunity to do some more maps but also to give the readers a little bit of a break and help the book stand apart from The Inheritance Cycle. But I wouldn’t want to do the full formatted style that I did for the Fractalverse in the World of Eragon. It just doesn’t feel appropriate.

I think for my next book, I’m gonna go with much shorter chapters. I want to experiment with that.

AG: What does your research process look like? Does it change when you’re working with fantasy and when you’re working with sci-fi?

CP: I’ve probably done a lot more research for the science fiction because with fantasy, at least the type of fantasy I write, involves things that we are fairly familiar with in the real world, you know. Horses and trees and mountains and castles and politics and people. Whenever I feel that I’m not familiar with something, I’ll always go spend some time reading up on it to make sure I’ve got some idea of what I’m talking about and I’m not perfect with this. There’s plenty of things I should have done more research on and I only realised after the fact. It’s a balancing act between research and writing time so I just try to make sure I’ve got a good feel for the subject material and then just attempt to be internally consistent with it.

AG: In Murtagh, the dragon and rider relationship was easily comparable to Eragon and Saphira. But at the same time while I was reading it, it felt unique. Was there anything on the craft level that you did to make it feel unique or was it just subconsciously those were the characters?

CP: I made conscious effort to write them differently than Eragon and Saphira and to have their relationship be different than Eragon and Saphira and I got about 80% there on the first draft and then did a lot more tweaking on the second draft to get it even further. I can give you a couple of small examples: Eragon and Saphira will often speak to each other with their minds and Saphira rarely will speak to other people with her mind. She’ll usually speak to Eragon first. And you know, it’s a big thing if she decides to touch someone else’s mind. With Murtagh and Thorn, Murtagh usually speaks to Thorn with his voice. Because he’s always guarding his thoughts even sometimes from Thorn. And Thorn is a little more open to just speaking to anyone who’s around him. Their interaction in general is as I say in the book, it’s more thorny, a little more prickly than Eragon and Saphira and I think Murtagh is a little more protective of Thorn. The relationships are different and that was important for me to try to capture.

A Little Bit of Magic

AG: So I want to switch topics to a little bit to magic. There’s a lot of conversation specifically about hard and soft magic systems. Before I ask you about those I wanted to ask your opinion on what do you think is the purpose of magic in fantasy or any other genre? Why does magic exist in them and why are we so very intrigued by it?

CP: That’s an interesting question. No one’s asked me that before. My gut reaction is that there are many different reasons for having magic in a story. You know, someone could approach magic in a very scientific manner. Brandon Sanderson does it in a very mechanistic manner so to speak. Then there’s magic that’s used like Tolkien’s, which is much more in the mythic vein of things and one could argue that it’s emotional magic, you know, it occurs when it needs to occur. You can’t really logic it. Or maybe you can logic it on a really deep level but that level isn’t shared with the reader explicitly.

Gandalf’s powers come from, essentially God or gods and he’s an avatar and a representative of that power on Earth or Middle Earth. There are limits to it but we don’t know what those exact limits are and that’s always the problem. That old style of magic can be incredibly powerful in a story because it works on the level of emotion. It’s almost like dream logic.

But without the constraints of logic, or mechanics, it’s very easy for it to get away from the writer or the storyteller and it ends up feeling like a crutch. Also if magic existed, then you have to ask does it come from a deity or is it like a naturally occurring thing? And that’s a big division because if it’s from a deity, then you have to think about it differently, but if magic existed then I think that people would want to understand it and they would want to exploit it and they would want to wield it. Then you’re essentially moving into the scientific method.

I always talk about it like exploits in a video game. [Magic is] doing something that is normally forbidden by the rules of the universe and in video games, you see how many people will use exploits and glitches once they discover them. I think people would do the same in the real world if magic allowed for that. You could argue that science and technology is our version of that.

So why do we use magic? Well, it serves a lot of different storytelling purposes. Also a lot of people — I am rambling here, but it’s an interesting topic — a lot of people think about the world in a magical way. It makes sense to include that in a story. But why do we keep coming back for it? I don’t know, I think because it makes the world interesting. To be able to do things that are normally forbidden. Perhaps it also satisfies that emotional logic within us. You’re out walking and a thunderbolt strikes something in a field and you think well, there must be a reason that thunderbolt struck there and boy wouldn’t it be cool if I could use the thunderbolt and the lightning bolt and strike there.

So, I think ultimately it appeals to our emotions.

AG: That that’s a great way of looking at it. I sometimes think of the physics that we have as a hard magic systems that we are just bound by these rules. But we are very keen to try and break them.

CP: I think we lose appreciation for what we have gained through technology sometimes because we get so used to it. I mean we are currently speaking to each other via magic mirrors.

And computers! We took some rocks and we put lightning in the them and made the rocks think.

Right on my desk. I have a light bulb that suspends itself over a magnet. It hangs in the air and rotates and if I were to go if I were to go back a thousand years and show people they would go, that’s magic. They would think our computers are magic and they’re not entirely wrong.

AG: If you’ve ever read The Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan there’s one scene where the character lights his candle with the use of his magic and he just thinks that it’s these small little conveniences that he loves most about the power. Now we have the same thing in smart devices where we can just switch off the light with the tap of a button. Is convenience then, what we look for — through magic or science?

CP: Well, we get so separated because of our technology. We get so separated from the things that actually allow us to survive. Food production, commodity production, resource production, and energy production. There are no rich countries with low amounts of power consumption. Or production. If you look at the graphs of the rich countries, they produce and consume a huge amount of electricity and energy and there is no way around energy. The Industrial Revolution is harnessing the energy of steam and coal and electricity. Without that we don’t have modern society.

I’m going on a tangent here but if we were really truly serious about climate change and about kickstarting our progress as a species, we would embrace nuclear energy left right and centre and until we do I don’t take anyone seriously about saying we got to fix it. We got to fix it, yes but they’re not willing to go that route because that would allow us to advance enormously and especially if in the long term if we’re going to be jetting around in the solar system.

We’re going to be doing it with nuclear rockets because chemical rockets just don’t have enough room. Thank Delta-v for that.

AG: Speaking of energy — in Eragon, you showcase a hard magic system where Eragon has to have enough energy to cast any kind of spell. How did you craft this entire system of magic within the world of Eragon? While you were crafting it, did you have to sort of change any of the story beats because the magic could have just solved the problem?

CP: In retrospect, I would have put more restrictions on the magic system because I find restrictions interesting. They lead to interesting and complicated situations, which are wonderful for dramatic storytelling. I started with the assumption that conscious living creatures and even some non-conscious creatures but living creatures in the World of Eragon can directly control energy with their minds or with their will. Not all of them but you know good chunk of them can do this.

To do anything with that energy requires the same amount of effort as it would to do it via any other means whether it was steam power or your muscles or electricity, whatever. Of course, there is no such thing as energy. It’s electricity. It’s momentum. It’s heat. There’s always a form. There’s not some abstract thing that’s energy. So that was my initial assumption and then everything after that came from those two assumptions. Living creatures can control manipulate energy with their minds and it takes the same amount of energy to do things via any other means. What come after has just been a natural extension of those assumptions. There have been some artificial constraints such as postulating that one of my species bound Language to Magic/Energy in an attempt to avoid the negative consequences of casting a spell and having a wandering thought pop in your brain that alters the intended spell and causes an explosion or something else.

But everything else came from those two initial assumptions and I just tried to follow the logical consequences.

AG: I really enjoyed the extension of the magic system in Murtagh which felt like a coding language. If this happens then that happens. It felt like a natural extension of the magic system and it was great to see that evolution.

CP: Thank you.

Book Lore

AG: In the acknowledgment of Fractal Noise, you wrote about how you don’t want to write anything dark and nihilistic. The first draft of Fractal Noise was dark but you turned it, I wouldn’t say into a happy ending, but you gave it a positive spin. How did you form that philosophy and why do you not want to write a story which ends in a dark place?

CP: Well, I think my philosophy, not my philosophy necessarily, comes from my experience with myself and those I love and watching others. Life is often extremely hard for people. Even those who seem to be living a charmed life often have struggles that are not immediately apparent. I don’t want to make that worse for anyone over the years. I have heard from hundreds and hundreds of readers who have told me that they’ve been touched by Inheritance Cycle, that it helped them in the difficult times of their lives.

Whether that was with depression or grief or any number of other issues. It’s made me think that if a book can help you when you’re in those dark places, then it could just as easily hurt you. I don’t want to be responsible for that. You know, I’m not saying that every book has to be sunshine and roses. Fractal Noise certainly is not sunshine and roses. It is a dark book, but I tried to say something worthwhile and tried to ultimately, if not on sunny note, at least leave it in a place where the main character is starting to move in a better direction. Because I feel like the great challenge of adulthood in many ways is figuring out how to deal with the adversities that life presents us. Given the societies have become increasingly secular over the years, I actually joked with my editor that Fractal Noise is not a book that would necessarily exist in anything resembling the current form in a more religious society. The question that the main character is wondering would be if it’s God’s will, trust in God, the faith which he could wrestle with. Those questions have a long tradition in literature, but it would be a very different type of book. But if the answer is not one’s faith, then it goes in a different direction. Regardless of how one chooses to ask that question, the real question is how to deal with adversity in life? I still think that question is perhaps the defining question of adulthood in many ways.

AG: Obviously, it is beautifully written. That thud. It has a rhythm of its own which I absolutely enjoyed reading.

CP: Thank you! The funny thing is on Goodreads people are either giving it like one star reviews or four or five stars. People are very very split on the book. And I totally understand. I mean if I didn’t if I weren’t in the right mindset for it, I would hate it, absolutely hate it and also I could see how it could come across as thuddingly obvious to some readers. All of which I think would be fair criticisms. But at the same time, it was one of those things I had to write to get out of my brain. And that was the only way I could write it so…

AG: I’m glad you did. Oh, are there any other one off books that you’re planning?

CP: Many and that’s one of the big reasons for creating the Fractalverse. I want to write books that are not explicitly World of Eragon, so those can go into the Fractalverse. But I also have some big series books in that world that I need to write first, so people have a better idea of what I’m actually doing in the Fractalverse.

AG: When you were writing the the Battle of the Burning Planes (in Eldest), you tweeted that you were listening to Woodkid. Is there any music that you’ve been listening to that inspired scenes in To Sleep or Fractal Noise or even Murtagh?

CP: Nothing that inspired it. But while I was writing To Sleep in a Sea of Stars, I listened to a lot of the Tron Legacy soundtrack. Also, especially the latter part of working on the book, I listened to the soundtrack to the video game anthem, which I know wasn’t a particularly successful game, but the soundtrack is gorgeous, especially like the first half of it. I absolutely loved it, it’s great for writing science fiction.

For Murtagh, I actually went back to stuff I was listening to while writing The Inheritance Cycle. So I was listening to the Lord of the Rings soundtrack. I was listening to Andean folk music which reminds me of the elves. Although there were a few places, I listened to the soundtrack for Aliens, which felt appropriate.

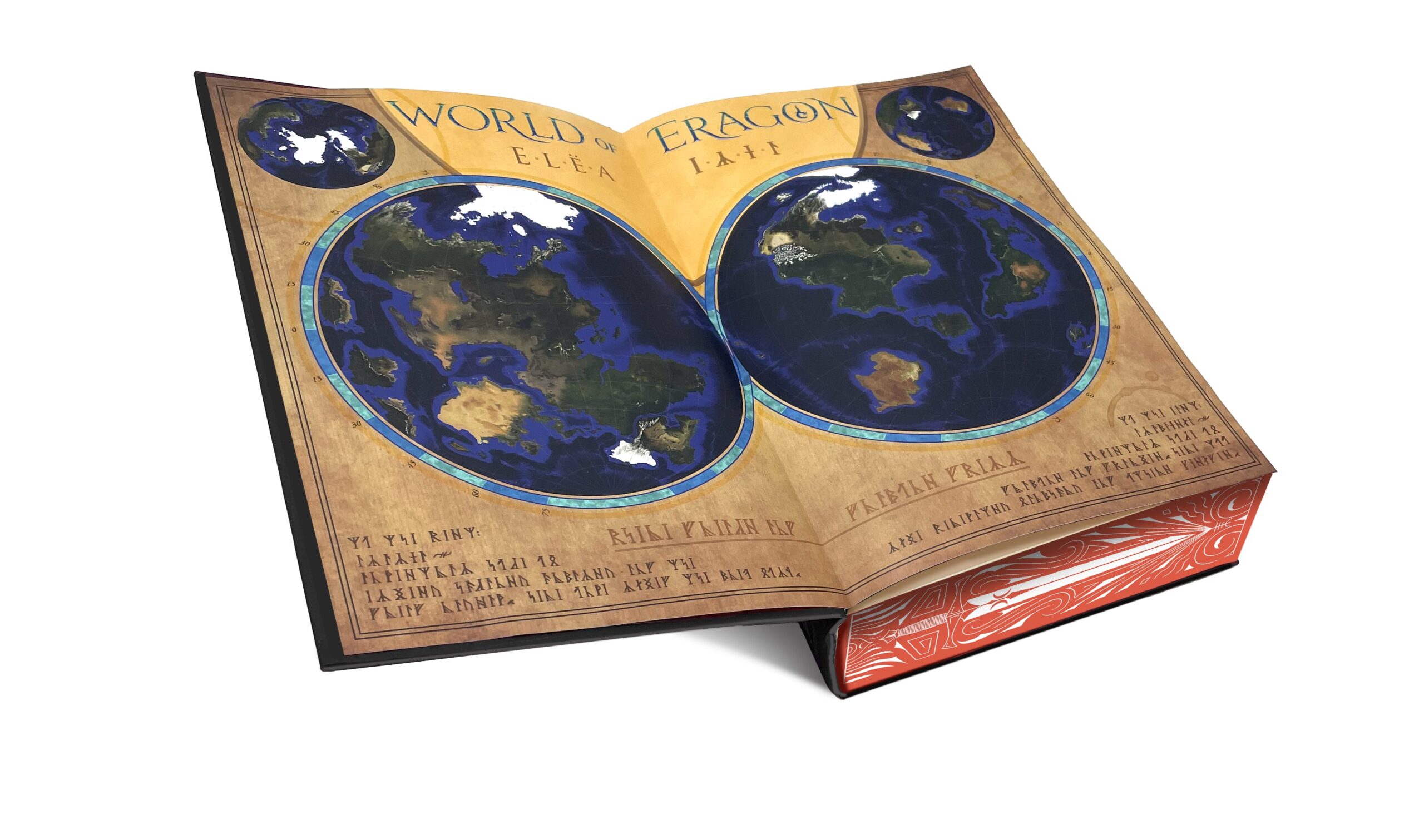

AG: In Murtagh, there were a lot more maps and in The Fork and The Witch and The Worm there was the extension of Alagaesia which revealed a lot more on the east of the continent. Are there more maps?

CP: Well, I literally finished this weekend revisions on a global map for the World of Eragon in full colour like a NASA satellite rectilinear equidistant projection. There’s a NASA program that lets you take a rectilinear projection and apply any other projection like this or that and so we’re getting that fixed up and all fancied up for a release later on.

So yes, that’s the big one that hasn’t been released.

AG: Amazing. I look forward to that! Will that be launched as a standalone map or will that be with a book?

CP: It’ll be released as part of one of the additions of the book. I can’t tell you exactly but I’ll share it once it’s actually out in public. I’ll release the map itself, so people can access it. The fandom can have their hands on it.*

AG: I won’t ask you what the next book in the World of Eragon will be but is there sort of a rough estimate when you would want the book to come out?

CP: I would like at least one book to come out next year but I have two television shows in development right now and I am contractually obliged to participate in both the shows. Of course, film and television tends to be all consuming. So I just don’t know how much writing time I’m gonna have for books this year. And that’s just the reality of it, but I would love to have something out next year.

AG: You don’t have to answer this but I wonder will you be writing from Arya’s perspective whenever you write the next book, maybe?

CP: No, not in the next book, but I have a book plan. That’s about 50% her point of view. So I just got to get there.

AG: I’m excited and rooting for you. Aside from the books you’ve planned, there’s this growing genre of fantasy fiction right now which is like cozy fantasy where you have a fantasy world, but the characters are just sitting around in the coffee shop drinking coffee and talking about life. Would you consider writing something in either the World of Eragon or Fractalverse which has a similar cozy vibe to it?

CP: Maybe… but I tend to like stories about exceptional events, epic stories. Fractal Noise is kind of the biggest divergence from what I normally write. When I do Tales from Alagaesia vol. 2, there might be some more of the type of story you’re talking about but the stories that have always appealed to me as an audience has always been, you know epic stories, big stories. And that’s what I’m drawn to writing.

AG: Would you be open to ever in the future opening up the World of Eragon or Fractalverse for other writers to come in and write?

CP: I’ve considered it. I did look at it one point, especially when I was trying to figure out if I could get Murtagh out the door when I wanted to get it out. The problem is I, for good or for ill, have a specific writing style which doesn’t necessarily read like any other author at the moment. It may be something I do down the road, but at the moment I’m still at a stage in my career where I’m just continuing to build the world and building the story of both the Fractalverse and the World of Eragon. That’s something I want to maintain control over.

* The book is the Deluxe edition of Murtagh. See here: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/753245/murtagh-deluxe-edition-by-christopher-paolini/

BOOK/Film Recommendations

AG: Are there any fantasy books you read in the last few years that have stayed with you or you wish you’d have written it?

CP: No, I have been horribly deficient in my reading in the past few years because of the writing deadlines and having two kids in two years. So I read Fourth Wing** recently. In the past few years, Kings of the Wyld*** was fun.

I really haven’t read any fantasy that’s really stuck with me recently. Probably the book that I read that stuck with me was Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy, which kind of reads like fantasy in places? Aside from that I’m reading a book called Traitor. And it’s fantasy. It’s kind of all about trade wars and imperialism. I can’t remember the author’s name unfortunately.

But I read so much fantasy growing up and in teens and 20s and I really would love to read more but I find as I’ve gotten older it’s harder and harder to get into books. And that’s a failing of my own. Perhaps it’s just having read so much and I spend every day writing, sometimes the last thing I want to do is look at more words at the end of the day.

AG: Do you ever listen to audiobooks?

CP: No, no, I hate it. It’s too slow for me. I don’t absorb the language well listening to it for whatever reason.

AG: Fair enough. When you were learning the craft of writing stories, were there any books that helped you understand how to tell a compelling story?

CP: Oh, yeah. I could not have written Eragon without a book called Story by Robert McKee, which is a classic screenwriting book and goes deep into the mechanics of storytelling. And that was incredibly helpful for me because up until that point in my life. I hadn’t really considered the fact that there was a mechanical aspect of story and that one could study it and attempt to master it. That was really responsible for my success to start with.

Since then books that have been helpful are Shakespeare’s Metrical Art by George T. Wright that really helped me with incorporating various poetic techniques into my prose. Other books that I’d read on poetry just failed to answer certain questions. I’d had very technical questions and that book answered them. So I’m a big fan of it.

Then there’s a book called Style by F. L Lucas which to my mind is the best book on prose style that I’ve ever read. [Elements of Style by] Strunk and White have some various inconsistencies and Style is much more organised, much more useful and does a great job of explaining why different eras have different prose styles like the victorians versus other eras. I’ve also read Into the Woods by Thom Yorke and examination of a 5 act story structure. I’ve really enjoyed that because it talks about the 5x story structure which was used by Shakespeare and quite a few others. A lot of playwrights use that. That’s what I did in To Sleep in a Sea of Stars. I used a five act story structure, which is why some readers have felt like it has one beat too many. I did it on purpose to specifically create the feeling that it was almost like a series within one book. It was a longer story than you would normally get with a 3 act structure. A lot of Bollywood films also use the 5 act structure, which is interesting. So I’m I really enjoyed that book.

Also Anatomy of a Story by John Truby. I think the fun thing about Into the Woods is he starts his book by criticising Anatomy of a Story. So there is no one way to write a story but it helps to read all of these books. They have all been enormously helpful and it does help to read about how other people approach that art and craft of writing and storytelling.

AG: Makes sense. I’m Indian and I’ve grown up on Bollywood movies. And is there any Bollywood movie that you’ve enjoyed?

CP: Well, let’s see: DDLJ, Jodha Akbar, Lagaan. I know it’s Tamil, but Bahubali One and Two, Main Hu Na — that’s such a funny film. I’ve seen a lot of Bollywood films. Oh all the Krish films. I mean those are better superhero films than most anything coming out of Hollywood and I love the colours.

I started with Lagaan because it was nominated for the Oscars the year it came out and then after that it was like this cricket match was as epic as any of the fights in Lord of the Rings. I need to see more Bollywood and I am going back to a bunch of the films by Guru Dutt. Boy, those like Pyasa — those are powerful films. If you’re a storyteller, it is helpful to see stories told from different cultures and different parts of the world.

In Western culture, there’s essentially no reason now why two people can’t be together. You’re black you’re white. You can be together. Oh, you’re Jewish. You’re Catholic Oh, you can be together. Oh you’re poor. You’re rich. You can be together. But in Bollywood, well, mommy and daddy don’t approve of this match. Guess what? You’re not getting married. Or you’re different castes or religions and it’s a big deal. It creates such a great conflict for a romance.

Western stories just don’t have that at the moment. We also don’t do romance for men anymore. I’ve watched an enormous amount of Hollywood films. Western films going back to the silent era with classic Hollywood romance movies for men. They used to be: a young man leaves home from the farm and goes to the big city and gets a job. There he meets a nice young woman who’s a sales lady at the store where he’s working. He has to prove himself to her and win her hand and impress her doing something. But it’s from the man’s point of view instead of the woman’s. When was the last romance movie for guys made?

I remember when I showed my wife Bahubali and she was like, oh, it’s a really long film. It’s kind of late in the day. I said let’s just watch a little bit and see what you think. I think that might have actually been the first Bollywood, no, Tamil film that I showed her. We got about 15 minutes in and I look over at her and she’s just locked in. We watched the whole first film. Then she looked at me and said we have to watch the next one. We watch both of them back to back. They are so epic. It’s amazing.

** Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros

*** Kings of the Wyld by Nicholas Eames

Akshay Gajria is a London-based storyteller, writer, and writing coach. He holds an MA in Creative Writing from Birkbeck, University of London and completed his Computer Engineering from NMIMS, Mumbai. He has ghostwritten two books and his writing has appeared in Skulls, The Writing Cooperative, The Written Circle, Bluegraph Press, The Coffeelicious, Your Story Club, Futura Magazine, The Book Mechanic, Poets Unlimited, StoryMaker, Whiplash and more. He usually struggles to finish his sentences… but gets to them eventually.

The Fall Of Troy by William Doreski

A false dawn awakens us.

The right time, when the cloud-facts

explain us to each other

and absorb the spilled light.

An era of rhetorical skies

precedes another great war

with all its pomp and circumstance.

Where will we pitch a tent when

ghost armies occupy our basement

with feint and struggle all night?

You want the sentiments to pile

like rugs from the Middle East.

You want the bass clef to dominate.

I’d rather lie on the sofa

and act as a cat trampoline

while the political class sheds

the last ethical gesture and stands

naked and shameless in the snow.

Christmas may or may not

arrive soon enough to save us

from bellowing little villages

armed with naïve ambitions.

We’ll drive through these places the way

Einstein drove through time and space.

Can we simper ourselves to sleep

for another hour while the clouds

argue among themselves? The fact

of the fall of Troy still lingers.

William Doreski lives in Peterborough, New Hampshire (USA). He has taught at several colleges and universities. His most recent book of poetry is Venus, Jupiter (2023). His essays, poetry, fiction, and reviews have appeared in various journals.

Little Thieves by Susan Gordon Byron

Dali’s clocks were sincere. They slipped over things, slid past and took nothing with them.

They changed. Or I changed them.

Pickpockets.

In the library, while I was staring into space – I had given myself up to laziness, swung in a hammock of not doing – a little gang of clocks slipped down a staircase of books and off the desk. They smothered my words and ran off with a deadline.

I declared Dickens boring. Shakespeare just impassable. With too many princes. I thought nasty things about the librarians, planned for a life without a degree.

I had got quite far into this new fiction when I saw them laughing in the courtyard. They’re not Dali’s clocks, I realised. They’re mine. And I gave chase.

Susan Gordon Byron is a non-fiction editor and podcaster in London. Her poetry has appeared in Dust and tiny wren lit. After a NCTJ postgraduate diploma in newspaper journalism, she worked at the Catholic Herald for two years. She hosts The Culture Boar Podcast.

MIRLive : July 5th 2024

MIR (The Mechanics Institute Review) will be holding its third and final live event of the academic year on Friday, July 5th (Keynes Library, 43 Gordon Square, 6:30 pm). The event will include eight readings, including six from current Birkbeck BA and MA creative writing students and two guest speakers: Sarah Leipciger, author of three novels including the acclaimed Moon Road (Doubleday UK/Penguin Canada 2024) andTony White, author of six novels including Foxy-T (Faber, 2003) and The Fountain in the Forest (Faber, 2018).

The MIR Live team

Sarah Leipciger is the author of three novels: The Mountain Can Wait (Tinder Press 2015), Coming up for Air (Doubleday UK 2020, now being adapted for stage with the Leipzig Opera House) and most recently, Moon Road (Doubleday UK/Penguin Canada 2024). She has published several short stories and written op-eds for The Guardian and The Toronto Star. She has worked as Writer in Residence in various London prisons, and is currently working towards a PhD in Creative Writing at Goldsmiths University. Sarah is an Associate Lecturer in Creative Writing at Birkbeck University, as well as a tutor at City Lit.

“Moon Road is a slow-burn story about people who are learning to live with the unthinkable and the unknowable. Leipciger has written an intelligent, nuanced book.” The Times

Tony White is the author of six novels including Foxy-T (Faber, 2003) and The Fountain in the Forest (Faber, 2018), three novellas, one work of non-fiction, and numerous short stories published in anthologies, journals and exhibition catalogues. A frequent performer of his fiction, White has been writer-in-residence at the Science Museum, at the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies, and for the Croatian city of Split. His reviews and articles have appeared in The Guardian, Irish Times, the Idler and 3am Magazine. Screen credits include scriptwriter on The Toxic Camera by Jane and Louise Wilson, and ivy4evr an interactive drama for mobile phones with Blast Theory for Channel 4. He is currently an Associate Lecturer in Creative Writing at Birkbeck, University of London, and has just been appointed a Fellow of the Royal Literary Fund.

‘White is always convivial company. His books are characterised by stylistic innovation, a feeling for place, a love of rogues and rebels.’ The Guardian

An Interview with Anthony McGowan

By JB Smith

Anthony McGowan was born in Manchester, went to school in Leeds, and now lives in London with his wife, two kids and a dog. In the past he has worked as a nightclub bouncer, a civil servant and a tutor in philosophy at the Open University. He is the author of over 40 books for children and adults.

juAuthors are a strange breed. They dedicate their lives to creating things of beauty, spinning webs of enchanting lies that show us the way towards truth. And yet to do this requires dedication verging on masochism that leads an otherwise sane individual to turn up day after day, week after week, as they attempt to pin the slippery threads of story to the page like trying to wrestle an eel into a jam jar.

I can’t think of anyone who embodies this split sense of character better than Anthony McGowan, the award winning author of over 40 books for children and young people, yet a writer whose career encompasses everything from literary thrillers to a treatise on how to teach philosophy to your dog. His books often draw on classical literature and he has a PhD in the philosophy of beauty, and yet to talk to him you get the sense of an unpretentious, no-nonsense writer who just gets on with the job. We meet on Zoom and he speaks in a rapid-fire stream of anecdotes propelled by self-deprecating humour and enthusiasm.

For McGowan the theme of contrast began right back in childhood. He grew up in the sleepy village of Sherburn nestled among the fields and fells of North Yorkshire, but went to a tough secondary school in the sprawling outskirts of post-industrial Leeds. His parents were nurses, which marked him out as distinctly middle class compared to the poor kids around him. But rather than dwell on the difficulties, he tells me that it was at Corpus Christi Secondary School that the spark of writing was first kindled.

“There wasn’t a great culture of learning at school,” he says. “But I was one of the brainy kids.” And the early encouragement he received created a positive feedback loop. “When you’re thirteen and you get praised for something, you want to do more of it.”

The trickle of encouragement swelled into a lifelong love of writing. Promising essays became promising stories, and then came the dodgy teenage poetry which apparently is in the contract of every author to have written to impress girls/boys (delete as applicable).

By his mid-teens he knew that his future would involve “something to do with words.” But on leaving school that “something to do with words” was hazy and undefined.

His undergraduate degree turned into an MPhil and a life plan unfurled ahead of him. “I thought I would carry on in academia, then probably write one literary novel per decade.”

But instead of a comfortable academic job and a leisurely output of literary works he was spat out of university into the grinding boredom of the Civil Service. And if there’s one thing you can be certain of, it’s that office drudgery will either wring every drop of creative juice out of the dishcloth of your soul, or light a creative fire under your backside. Thankfully for McGowan it was the latter.

The dullness of work was the impetus that began McGowan’s journey into publishing, but the route he took was circuitous, bizarre, and completely unreplaceable.

While still a Civil Servant McGowan began work on his first novel, Hellbent, a wonderfully unhinged retelling of Dante’s Inferno in which a teenager dies and goes on a journey through Hell. And this first foray into writing fiction felt like the bursting of a dam. “It just poured out of me,” he says, eyes gleaming with the memory.

So far, so relatable. But this is where McGowan’s story veers off into the leftfield.

“The rejection was completely dispiriting,” he says. “I was determined to get into publishing, but I totally hit a wall. And then there was, well, kind of a funny swerve in my career.” He pauses for a moment, and looks away from the screen. I wonder if he’s about to change the subject but he smiles back into the camera and ploughs on with the story. “So I reinvented myself as a woman.”

This was the late 90s, post Bridget Jones landscape and so McGowan wrote two novels under a female pseudonym which landed him first an agent and then a book deal. I wonder if this might be even more bruising to his self-esteem, having been rejected under his own name but accepted with a false persona. But that wasn’t the way his mind worked. Instead of simmering with resentment, he sent Hellbent to his agent, who had no idea about the pseudonym, under his own name. She loved it and took him on in his own right.

Once again Hellbent was sent out. Once again it was rejected across the board, but this time with far more encouraging, personally written rejections. The general consensus being “this is amazing, but it’s unpublishable because it’s so weird”.

“So my agent suggested I write something more commercial, and I went away and wrote a literary thriller called Stag Hunt.” Off the back of two chapters and a synopsis he signed the biggest book deal of his life and success seemed all but assured. But here is where his story veers out of the leftfield, crashes through a fence into the ditch of downright horror. I’m surprised to see that he’s still smiling as he relates the story.

“Stag Hunt was published by Hodder and Stoughton. Beautiful edition. Nice reviews. Tesco bought tens of thousands of copies.” But here’s the kick. “The barcode had been misprinted and wouldn’t run through the tills.”

Tesco returned tens of thousands of copies and, in the blink of an eye (or the bleep of a till scanner) he went from being the hot new thing to the guy who got Hodder and Stoughton stuck with 40,000 copies of his debut novel. I’m about to suggest that the blame might lie with the person responsible for printing the barcode rather than the author but I think it best to let sleeping dogs lie. Instead, I ask if this left him feeling as utterly crushed as I would be in that situation. But it turns out a healthy dose of naivety saved him from becoming a gibbering wreck.

“The exhilaration of getting published at all meant I just thought, it doesn’t matter. It’s only a small set back. But what I hadn’t realised was how crucial a step it was. Tesco would have made it a best seller, and my career would have been underway.”

McGowan’s status was obliterated. The sequel came out with no press and sold effectively zero. And here we reach another point in McGowan’s journey at which most sane individuals would abandon writing and take up knitting or competitive marrow growing. But, to paraphrase Octavia Butler, the most valuable attribute for an author isn’t erudition or literary flair, but downright bloody mindedness.

Now that he was a known author, Hellbent was picked up by a publisher. The book was reworked for a YA audience, and McGowan had unwittingly stumbled into the career that would lead him to write over 40 books and win the Carnegie Medal, the most prestigious award for children’s literature in the country.

I ask if this was perhaps a more fitting career path given that his first inclination had been to write a YA novel without realising it. I can feel the follow up questions bubbling about the psychic landscape of childhood marking us out as writers for young people but McGowan gently smothers my armchair psychology with his pillow of cheerful pragmatism. “I would have been quite happy as a literary thriller writer,” he says with a wry smile. “It’s just that my books for younger readers are what got published.”

The next few years saw a steady stream of novels in which McGowan continued to hone his trademark humour, offbeat storytelling and vivid imagination. After Hellbent came Henry Tumour about a boy with a talking brain tumour, then The Knife That Killed Me which was made into a feature film. But the sales of YA fiction just weren’t quite enough to sustain a career. So his agent suggested he try his hand at writing for younger readers.

And so after his initial aspirations to academia and the odd literary novel, McGowan now found himself the author of such titles as the Bear Bum Gang, Einstein’s Underpants and the Donut Diaries. Many would see this as a demotion but that couldn’t be further from the truth. McGowan brought all the same intelligence, humour and imagination to his books for younger readers, yet still driven by the pragmatism of a writer who needs book sales to pay the bills. “A teenager might get through one or two books a month,” he says. “But a seven-year-old gets through three books a week with their parents reading to them.”

After he had a few books to his name, McGowan was approached by Barrington Stoke, an independent children’s publisher focussed on books for reluctant readers. And it was this relationship that would see McGowan write the series of books that became The Truth of Things, arguably some of the most moving and memorable novels for young people written in recent years, and would ultimately land him the Carnegie medal.

The stories follow two teenage brothers, Nicky and Kenny, navigating an incredibly difficult childhood in rural Yorkshire. Mum has left, dad is a recovering alcoholic, and the older brother Kenny has severe learning difficulties meaning Nicky has to act as his carer. But if that sounds like a litany of misery, then think again. Each instalment sees the brothers tackling life’s challenges with humour, love and resilience. Each story centres around an encounter with the natural world such as rescuing a badger who was attacked by terriers, and nursing it back to health. But this act of healing goes both ways, and gives them access to stores of resilience within themselves, and connects them to the larger webs of nature and landscape that elevates them beyond the humdrum of their lives.

But if my unashamed outburst of sincerity makes the books sound worthy or trite, then once more it’s time to think again. Nicky and Kenny are gushing torrents of the usual potty mouthed buffoonery that characterises most teenagers and there isn’t a shred of sentimentality to be found.

The books are told though Nicky’s voice which is a funny and deeply authentic encapsulation of a working class teenage boy. I’m keen to know more about his process of finding that voice on the page.

“I kind of think with my fingers,” he says. “It just comes out through the hands when I’m writing.” But that moment of “thinking through his fingers” is accessing a whole lifetime of experience. “You’re drawing on all of your memory. All of the things that have happened in your life which get squished and compressed by the geological forces of time in your brain.”

Talking about meaning in a story is always a bit queasy. Whenever Ursula LeGuin was asked what this or that story “meant” she would “smile politely and shut my earlids”. But story and meaning are inseparable, and the Nicky and Kenny books are some of the most and meaningful books I have read in the last decade. So I take a deep breath and tiptoe towards the subject.

The final book Lark sees Nicky and Kenny lost in a snowstorm on the Yorkshire Moors, following a stream as they try to find their way back to safety. McGowan weaves together so many threads of meaning and significance, with the river connecting to story, to the flow of our lives, to confronting the hardships of life with family at your side. I wonder if he’s thinking about those layers of meaning as he writes, or if he just follows the story and leaves the rest to his reader.

“I don’t think I did consciously think about those layers,” he says after a pause. “My whole process was about getting into Nicky’s mindset. At the end you discover that he’s the author of the story, so he has his own poetic sensibility. So if there are layers, they are Nicky’s layers rather than mine.”

No matter whose layers they were, they certainly resonated with readers across the country. Lark went on to win the Carnegie medal, which he understandably describes as the crowning moment of his writing life.

Having spent four books with the same two characters rooted in the soil he himself sprung from, McGowan understandably felt the pull of new horizons. And this led to his most recent book, Dogs of the Deadlands, which leaves the rolling hills of Yorkshire for the depths of the Ukrainian forests in the aftermath of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. But while the landscape had changed, McGowan’s fascination with the natural world had grown even stronger.

The story opens with the meltdown of the reactor that tears Natasha Taranova from her home, leaving her new puppy Zoya behind. From here the narrative splits, following Natasha’s attempts to adjust to life in Kyiv, but mainly focussing on Zoya and her pups who are thrust into a wild world of hunger, survival and wolves.

If the Nicky and Kenny books are close focussed and intimate, Dogs of the Deadlands is a sweeping epic; a post-apocalyptic Animals of Farthing Wood, where Fox rips Badger’s throat out in the first chapter.

The book had a long gestation period for McGowan, and the details of its conception are hazy. “I’ve told so many stories about the book’s origin that I can’t quite remember what’s true and what I’ve made up. I’m 90% sure that the idea began when I saw a National Geographic documentary about the rewilding of Chernobyl.” His eyes light up as he relates a scene where a wolf pack has taken over a deserted farmyard and one of the wolves jumps onto the roof of an outbuilding and howls. “In my memory you could see the ruins of Chernobyl in the background,” he says with a wistful smile.

From that image the seed was planted, but the soil was already fertile. McGowan was captivated by nature from a young age, and it was the natural world rather than the human tragedy that attracted him to the story.

“My fascination wasn’t so much the accident but the rewilding. When the humans left, the big herbivores moved in, then the big predators. So, because there are no people, it’s a fantastically rich and exciting place.”

And the book that grew out of McGowan’s fascination is equally as rich and exciting. It’s gripping and heart breaking, violent and life affirming, and the interior lives of the canine protagonists are brilliantly rendered on the page. I wonder how hard it was to balance making the animals understandable to a human reader while not anthropomorphising them beyond recognition.

“I didn’t want my animals to speak like little humans like the rabbits in Watership Down. I couldn’t make them completely animal, but I wanted the book to be true to the brutal reality of their lives and not romanticise them at all.”

And he certainly doesn’t romanticise the lives of the dogs. Their existence is a constant balancing act between evading starvation whilst not becoming a meal themselves.

As we reach the end of our allotted time, I try to give the interview a semblance of structure by asking a question about endings. There is something incredibly special about the feeling of getting towards the end of a good book. The sense of propulsion towards the narrative conclusion, the bittersweet feeling of a good story coming to an end. I wonder if he feels the same as he’s approaching the end of writing a book, or if he’s just happy to get the dratted thing done?

“Generally speaking, when I start writing a book I already know the ending, and usually there’s a momentum building as I get closer.”

He circles back to the ending of Lark which is one of the most beautiful yet heart wrenching endings I can remember. The series appears to come to a climax with the return of the boys’ mother, but that scene ends and there are a few pages left. We flow forward in time and see the life of Nicky blurring past, and we end beside the hospital bed of Kenny who is dying of cancer, at the very moment Nicky decides to pick up a pen and begin writing the stories we have been captivated by for four incredible books. When I first read that scene I must have looked like I had been chopping onions for days, but the emotion didn’t just go one way.

“A couple of years after the book came out I did a school visit and the teacher asked me to read the final part. But I had kind of forgotten what happened. When I got to the last bit, I actually started crying in front of all these kids. So that was when I realised that yeah, the ending worked out ok.”

Review: Encounters With Everyday Madness by Charlie Hill

Summer Kendrick reviews Encounters with Everyday Madness by Charlie Hill

Charlie Hill’s Encounters with Everyday Madness (Roman Books, 2023) isn’t just an exploration of modern madness, it tilts the concept completely, leaving the reader to decide: what is normal, anyway?

From the author of The State of Us (Fly on the Wall Press, 2023), Books (Profile Books, 2013) and The Pirate Queen (Stairwell Books, 2022), Charlie Hill’s latest book, Encounters with Everyday Madness, follows suit with a bold and rather wry collection of short stories.

Aptly named, each story chronicles a brush, and sometimes a crash, with the uncomfortable truth of the inner mind. The word ‘madness’ covers all manner of states – whether it’s the crushing weight of anxiety, the manic conversation of a presumed junkie or the eeriness of going for a walk through an isolated forest. Hill presents each story like a case study, but refuses to make judgement on who or what is crazy. In fact, the reader begins to believe that craziness is an inevitable condition of being human.

Hill plays with form throughout the book, to great effect. Some stories are epistolic, others are poems, reports or trailing snags of small talk on the School Run. The use of experimental form compliments the overall theme and objectives of the collection, reminding us that rules and reality are flexible conditions.

A Walk by the River, the opening story, was particularly strong. Second person is notoriously hard to master, and while the internal dialogue was jarring, the POV lended powerful interplay between nature and the mind.

Madness can often manifest in isolation and loneliness, which was the principal challenge throughout. With a few exceptions, Hill handled this with extraordinary care and humour. Some stories, such as Stuff, were prone to lengthy monologic exposition that diluted Hill’s otherwise punchy and wry writing style, but the clear voice in Love Story and Temping kept the pace up throughout the collection.

Hill establishes a very working class British tone of voice, consistent with his other works, through most stories. He uses the quotidian bore of waiting for a bus, making a frozen dinner or building Lego to create complex characters who challenge the concept of sanity. Encounters with Everyday Madness is an uncomfortably poignant and successful tribute to madness, in all its shapes and forms

Charie Hill. Encounters with Everyday Madness. London, Roman Books, 2023.

Summer kendrick is joinT editor OF MIR and A recent alumnus of the Birkbeck Creative Writing MA. She is currently writing a novel set in London and Australia.

Review: The Rabbit Hutch by Tess Gunty

Natasha Carr-Harris reviews The Rabbit Hutch by Tess Gunty

Tess Gunty’s widely acclaimed debut novel takes place in fictional Vacca

Vale, Indiana, an obscure town in the Rust Belt of America which we discover early on has topped Newsweek’s notorious list of “Top Ten Dying American Cities” (31). At the edge of town, a motley cast of characters fight to survive and aspire to thrive in separate units of a low-cost housing complex, a building named “La Lapinière”, or “The Rabbit Hutch”. Unfettered by the restraints of chronology, Gunty takes the reader on a polyphonic dance that offers both fleeting glimpses and cutting insights into the sad decline of a once bustling industrial centre and the characters who struggle haplessly against the oppressive systemic forces that disrupt and upset their lives.

There are grand, overarching themes which loom portentously over the unfolding personal narratives, omens of ecological doom and economic collapse and a depressing paucity of societal communion, all echoed by carefully detailed accounts of the city’s deterioration and stricken portraits of its unhappy denizens. What we learn about Vacca Vale’s decline throughout the novel seems to substantiate the current discourse on the predicament of America’s Rust Belt. The Vacca Vale river, which cuts through the city’s centre, is hopelessly polluted, countless businesses foreclosed, shops, buildings and houses abandoned, streets littered with trash, and we soon learn that the town’s only bit of untouched beauty, an expanse of park called Chastity Valley, is set to be transformed into a cluster of condominiums as part of a development plan.

Blandine, the eighteen year old star of the novel, opposes the development plan and stages an unnerving protest during a celebration dinner for its official launch. We witness her quietly agitated moments before the attack, poised on the precipice of dissidence, desperate to defend the Valley, embroiled in a strange, unsettling conversation with Joan, another resident of the Rabbit Hutch. The actual attack occurs off page, but I was far more interested in these preceding moments of inner turmoil as they set the stage for what we will come to learn and expect of Blandine: her fascination for mysticism, her uncompromising principles and ideals, and above all, her particular brand of profound loneliness.

Precocious yet troubled, Blandine strikes me as a conduit for important and necessary criticisms about the state of her hometown and the crises that permeate our reality at large. Freshly aged out of the foster system and unceremoniously thrust into adulthood, we find her cohabitating with three teenage boys who come from similarly unstable backgrounds, grappling with the trauma of having been betrayed by a mentor figure, a teacher from her old school. As much as her intelligence helps her escape her pain through her readings of the mystics, she is bereft of the resources to actually help herself, and her awareness of how much is beyond her control

contributes to a terrible anger.

Described as beautiful in an unassuming, ethereal way, Blandine is undoubtedly set apart from the other characters, but I found a great deal of her sentiments, beliefs, habits and thoughts to be intensely relatable and resonant. For instance, in a conversation with Jack, one of the boys she lives with, Blandine delivers a scathing diatribe on the exploitative perils of social media and its contribution to a cultural erosion that leaves room for little else than artificiality and incessant comparison. In response to Blandine’s deliberate abstinence from social media, Jack accuses her of snobbery, to which Blandine replies, “Not at all. On the contrary, I’m too weak for it” (177). For me, this attitude succinctly encapsulates an aggravating paradox about people who avoid social media and those who long to break free from it: that they are principally opposed to the proliferation of “hacking, politically nefarious robots, opinion echo chambers, [and] fearmongering,” yet equally as susceptible to its addictive algorithm (177). But as articulate as Blandine is when it comes to expressing her discontentment, she is helpless to effect any real change. She is as much a relatable nobody as a burgeoning mystic, all of which makes her role in the novel’s harrowing climax both tragic and poetically satisfying.

True to its polyphonic structure, the novel is stylistically experimental with a wide range of perspectives and voices which range from finessed prose with rhetoric, metaphors and sensory detail to the colloquial chatter of a teenage boy. There was one chapter I found quite striking in its unprecedented structure: in the aftermath of the novel’s climax, nineteen year old Jack relays the sequence of events that culminate in the story’s final, violent confrontation through a chapter composed solely of single-sentence paragraphs. Entirely devoid of effusion, the terse list of one-liners resembles a factual police report and I was left with a curious sense of emotional obstruction and an understanding that perhaps for Jack, the horror of what transpired necessitates a sort of removed detachment.

Here and there, the fragmented narrative dips delicately into surrealism, never departing too far from the banalities of real life. Many of the characters come from different walks of life and subsequently face a scattered array of hardships unique to their backgrounds, though they share humanising attributes. But before they are real, they are merely strange. One of the first things we learn about Moses Robert Blitz, for instance, is that he habitually stages nocturnal attacks by covering his nude body in glow-stick liquid and breaking into the houses of his enemies to frighten them. What could possibly motivate his bizarre behaviour emerges as puzzle pieces from a painful past that he cannot let go of; these pieces all point to a mother who hurt him deeply, and has recently skirted any possibility of resolution or reconciliation through death. Meanwhile, the mother in question, the Hollywood starlet Elsie Blitz, is as haunting and formidable in her living moments as she is in death. In a truly innovative auto-obituary, she offers a haphazard collection of life lessons, chastises her adult son for his nocturnal escapades, and outlines a startlingly vivid encounter with Death himself. Moses eventually arrives in Vacca Vale on one of his punitive missions, but he and Elsie are the only two characters whose lives actually take place outside of the town. And while they certainly embody what the dying town lacks—namely, wealth—it is equally as clear that they are not impervious to its smog of despair. The relationship between Moses and Elsie, which explores fundamental misunderstandings and limitations on both ends, was, for me, one of the novel’s most convincing portraitures of a dysfunctional relationship, and certainly my favourite. As Gunty pithily summarises: “In the end, there was a woman and a man. But the man was too much son and the woman was too little mother” (166).

I enjoy my fiction with a touch of surrealism, which exercises my imaginative faculties, but what I was not expecting to enjoy was how much the internet features throughout the story. We live in a virtual age, after all, though this is a fact that I am not always at peace with, so when a book succeeds in depicting the online world authentically, replete with internet vernacular, emojis, typos, and the kind of unsightly language borne behind the safety of anonymity, I find myself genuinely paying attention. One of the Rabbit Hutch tenants, Joan, ekes out a living screening obituary comments for “foul language, copyrighted material, and mean-spirited remarks about the deceased”, amongst other varieties of unruly internet conduct (34). In a chapter wholly comprised of obituary comments, Gunty relays a barrage of offensive material that Joan is forced to delete. At first glance, the comments seem nonsensical and random, as internet content so often is, but there is, in fact, much to glean from the remarks on what is ailing us all. One comment, in all caps, promotes a young hopeful’s new music album; another spouts political non-sequiturs; yet others spell out conspiracy theories, sexual propositions, requests for charity, and even existential provocations. In these pleas for attention and shouts into the void, I gathered a core truth about what Joan calls the “collective American subconscious”: that America may be lost, but Americans are fighting to find themselves.

I have included in my review those moments from the book that struck me most viscerally, that I can recall without effort and feel a great urge to discuss with others, but I have no doubt there is much I am forced to overlook—or have not yet discovered—and I would urge any reader to look for those moments of humour and insight. As much as it comments on the state of America, The Rabbit Hutch meditates equally on modernity, and people, such that while my reader’s greed longs for more, I have to defer to the novel’s unresolved ending, which mimics what we know of the questionable nature of life.

Gunty, Tess. The Rabbit Hutch. London, Oneworld Publications, 2022. Print.

Breaking Kayfabe: An Interview with Wes Brown

It takes awareness, intelligence and creativity to compete professionally at sport. Its exponents have to process multiple sources of ever-changing information in real-time and react accordingly, trusting their body to back their decisions. It’s arguable sportspeople are not given enough credit for how good they have to be to compete at the highest level; they are judged on post-match interviews and PR-filtered press conferences, and only their counterparts and opponents truly know what it takes to survive and thrive in any given sporting arena.

Some sports are given more licence than others. No one is surprised when a cricketer speaks eloquently about landscape painting, nor when a loosehead prop quotes Greek, but these are sports most readily associated with expensive educations. The wider world expresses amazement when a Rugby League player has Grade 8 piano, or a footballer is studying GCSE Maths. There’s snobbery involved.

Professional wrestling might be the sport we expect least of. For many people, wrestling is Mick McManus fighting Kendo Nagasaki of a Saturday teatime, or a mulleted loud-mouth from Idaho smashing a tea-tray across an opponent’s head. We don’t imagine there are participants deconstructing the sport, examining its many layers of reality, and dreaming new ways to blend its combination of performance, athletics and theatre. There are people who don’t believe it hurts.

Wes Brown is a professional wrestler from Leeds, the son of wrestler Earl Black; he’s also a novelist and poet, and the Programme Director of the MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck. Wes grew up grappling with his brother in his dad’s front room, and piling through book after book at Leeds Modern, the alma mater of Alan Bennett and Bob Peck. His novel, Breaking Kayfabe, published by Bluemoose, is a retelling of his career as a wrestler and his growth as a writer, as he developed his strong style of wrestling and his ‘no style’ of writing.

Were you always a writer?

I began to get creative in my teenage years. I was in a short-lived band that didn’t go anywhere. Film was my main thing. We made a short film that was the only non-funded short film to be included in the Leeds Young Persons Film Festival.

But the bother of getting a location, getting equipment, working with people: it was a logistical nightmare every time I wanted to create something new. It got too much. You could have a vision for a piece but it might require a CGI budget of $700 million, or something ridiculous, yet if you write ‘thunderstorm’ in a story, there it is, a thunderstorm. I realised I didn’t need all those other people.

So that’s how I started writing. I wrote poetry to begin with, and weird genre stuff. I saw an advert for an Arts Council-run writing programme called the Writing Squad, that was open to writers in the North. I got on as a wildcard entry. They’re still going today. It’s become a bit of an institution; all sorts of writers have come through it. There’s an analogy to football, to a youth academy, the idea that you can take people’s skills to another level if you create an intensive environment to support them. Otherwise, they’re left to their own devices.

From the age of 16, I had some poems published through the online version of Sheath magazine, which was connected to Sheffield Uni.

Was that run by Ian McMillan at the time?

It was, yeah. I also had poems published in Aesthetica, and one or two other places. When I was 18, I sold a short story as part of an anthology for Route publishing, who were a Pontefract-based fiction publisher who switched to publishing music books. I did an internship with them. I was quite young – eighteen, the same age as Wayne Rooney. I’d sold a story for 50 quid. I was the Wayne Rooney of the writing world, both breaking through. Nothing could stop me.

And then there was a period in the wilderness where I was experimenting, writing nonsense. When I was 24, I published a novel with a small press. And it was just bad: the novel wasn’t fully finished, I didn’t like the production, there were proofing issues. It just felt fake.

Round that point, there were other things going on in my life. I had a massive identity crisis for a few years, which lasted till I was offered the opportunity to train as a pro wrestler. The Writing Squad offered to pay my training fees, so long as I wrote something about it. And I thought ‘I’ve got nothing better to do. I’m pretty depressed. I’ll go be a wrestler’.

I got into wrestling training and literally became another person, Or at least, I pretended to be.

Were you still writing?

I went to Birkbeck at the back end of that. Doing my MA got me back on track with fact-based fiction, blending fact and fiction, as I felt that’s where I needed to be. The novelly novels and the fiction I had written felt cartoonish and fake. Birkbeck got me into a space where I felt my writing was a lot better. And that became the book, Breaking Kayfabe.

What was the benefit of the MA for you?

I spent a long time not being able to control my writing. Some good stuff would come out, and some bad stuff would come out, too. And people would be into the bad stuff or pretend to be. I thought people were Kayfabing me. I was thinking, ‘Do you really think this is good? Or are you just being nice?’ I had that doubt.

I was doing what a lot of new writers do, where they want to show that they can write. They don’t write normal sentences, because everything has to be about dazzle. And nobody is impressed. ‘That’s all very well, but tell us a story.’

And it wasn’t until I went through the workshop process on the MA that I realised what people really thought, and found I knew what I wanted to do.

Describe the connection between strong style wrestling and no style writing.

Sometimes I’ve wanted to write in a high literary style, and people have gone, ‘but that’s not you’. It suggests that if you’re southern middle class, you can write like that but, if you’re from the north, you can’t, and I thought, ‘Well, what if I want to have a literary style?’ But on the other hand, there is a kind of truth to it.

And through the MA, when dazzle didn’t work, I developed this new style that I call the ‘no style’ style. I wanted to write invisibly. I didn’t want my fiction to feel laborious. I wanted it to be a rush that I got into, that didn’t feel like writing. Weirdly, people reacted better to ‘no style’. I have a no nonsense, direct, colloquial way of speaking that I’ve grown up with, which I bring to my style of literature. It’s that flatness that makes the style different and literary in a way.

So I wanted to be strong style in the ring. And I wanted to be strong style on the page as well. In wrestling, there’s a phrase that no one’s going to believe it’s real but you want to make people forget that it’s fake. I wanted an MMA vernacular that would be plausible, that would be realistic and would look like it might hurt somebody, something you may use in a fight, to create that reality effect.

And so that’s what the ‘no style’ was. I wanted it to seem spontaneous, to deliberately not write well. And that was a risk because if you want to purposefully write with a little bit less gloss and a little bit less polish, it could come off like you just can’t write. But I wanted it to be a bit rugged, you know.

William Regal is a British wrestler who trained people in a WWE Performance Centre. For him, the aesthetics of good wrestling should be a little ugly. It shouldn’t look too choreographed. It shouldn’t look too clean, because it should still look like a proper fight. That’s what I wanted in the book. I wanted it to be a bit ugly. I wanted it to be a bit sort of rough and rugged. It wouldn’t be too pristine.

There was a macho man match in WrestleMania 92, or something like that, where they choreographed every single movement in the match. That was largely unheard of at the time, but it went over really well. Over time, that has become the template. Everything’s highly choreographed.

The alternative is to do it spontaneously. You call it on the fly. You feel the crowd. You feel the story of a match and just run with it. And I wanted some of that spontaneity in the book because I love calling it on the fly. In the ring, it adds a sense of unrehearsedness. There’s the thrill of the real.

And with the book, I wanted that flow. I wanted it to flow out of me. And it wasn’t always possible because it’s a difficult state to get into, but I didn’t want to do it in too cogent a way. So for the most part, Breaking Kayfabe doesn’t have chapters, but it’s got collections of scenes that constitute chapters, and I wrote each in one go. I did everything in one sitting. And if it didn’t work, I did it again the next day. I just did it again until I got it. So almost all of it is written spontaneously. I tweaked it a little bit, and the editors added stuff, but by and large, that’s how it came out.

If you’re blending fact and fiction, does that affect the reader’s assumptions about you?

There’s a Nabokov quote: ‘You can always count on a murderer for fancy prose’. And you can always count on a pro wrestler to be an unreliable narrator. They’re slippery and you never know when a pro wrestler is working you or not. That’s one of the joys of the book for me, because people don’t know. I like to see how much have I worked you. This could be a work, it could pretty much all be fiction. It could be a shoot – this is a wrestling term where it’s legit – or it could be a worked shoot, where I make it look like it’s a shoot, but it’s actually a work. Or it could be just a shoot, that I’m pretending is a work. Or it could be elements of all those things.

And people will want to know how much of it is true or not. One reviewer said I was greedy because I was trying to have this pro-wrestling character protagonist, who is also literary, making literary allusions. And I’m like, I am Dr. Wes Brown, literary critic, novelist, programme director of a Birkbeck MA: it would be unusual if I weren’t to think of literature. What am I to do, self-censor, just because he wanted some sort of wrestler who doesn’t think about these things?

Pro wrestling likes to introduce real-life elements, or sometimes real life intrudes into it as well, when people start fighting for real or real feuds come to the fore.

I want that slippery slope of how much of this is real, and never really give a conclusive answer.

At the time I was writing that section, I realised it was about my dad. So, the current protagonist in the story feels like it should be my dad, but actually that’s me. And the bear is my dad. And I let go of the bear, foreshadowing what’s to come. But also at the time, that was a very fictionalised way of dealing with some of these same things.

The whole story is a search for approval – as a writer, from the narrator’s father, from his girlfriend. It’s that about validation and acceptance.

It’s to do with status, and family as a micro society. You’ve got your own status in there: I’m now really important to those people. I’ve got people who depend on me, who I need to take responsibility for. I’ve got people I need to, in the best possible manner, be a dad for. I need to be a husband. I need to be a more whole person. Status is huge.

And I think, coming from a lower social status, and having difficulties in your upbringing – it’s not directly coming from my parents, but from circumstances as well, that you weren’t really wanted. Nobody really thought anything of you. It was all polite and there’s nobody really actively discriminating against you, it’s just nobody thought you were special. You were nobody’s favourite.

And you wanted to be the man you want to be. You wanted to be the champion. And then growing up in the big shadow of somebody like my dad: when you’re the son of a wrestler, that’s all you are.

What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a true crime book about Shannon Matthews, who was kidnapped by her mother. This happened in Dewsbury, not far from where I grew up.

The book started out as faction, as a David Peace-style story, which had the same themes as Shannon Matthews’ story, but which was not specifically about her. But I could never make it work.

And then I tried to make it an oral history, like Norman Mailer’s Executioner’s Song, but I found nobody in the community would talk to me.

I ended up doing it as some sort of true crime thing. I was worried it would be artless, merely a document of what happened, but actually, what I’m finding is, in writing this way, even though it’s nonfiction, all my skills as a novelist are coming to the fore. I’m trying to let the story come through the characters as the events happen, so the tension builds and any reflection or knowledge is revealed naturally. I’m not necessarily going into the heads of the characters because obviously I don’t have access, but you can safely assume that say, this person finds out this given fact at this given point. And I’m gradually pulling the story out, like a string, and not just bombing everything with exposition and knowledge and opinion.

I moved to this format because I wanted it to be as real as possible. I wanted nothing to be fictionalised.