Drim, by Nick Norton

Inside the villa they are taking no note of lines. Not of lines shall they be ruled, so it was said. Dr Ignatz is saying this.

‘For a day or so,’ (they whisper).

‘Soon enough,’ (they whisper), ‘best bet. They will be putting lines back in pronto.’

The villa was a house on the outskirts of a hospital, green expanse and trees surrounding. Dr Ignatz set the scene and it was she who said no more lines. From then on big V capital letter was quickly heard and so they now lived in The Villa, no longer patients but guests. Ruled and rulers sat down together. Rulers said the ruled could be rude or whatever: their show.

Journo Jim was knocking on the door.

Dr Ignatz wafted lyric-like, said she had wonder-drim and vision pictures. Ruled look to one another with arched eyebrow and mutter.

‘Ain’t that what got us in here in first place?’

‘I have a picture of progress,’ she says, ‘of how we are lifted when our hooks intermingle.’

‘Like Velcro?’ checks Geraldine Gee.

Geraldine is now in the parlance noted as guest but still she flinches at the sound of her own voice, expecting a battering. Expected battering does not come today.

‘Yes,’ smiles Doc. ‘Like Velcro, we lift the material together when our hooks intermingle.’

Journo Jim is knocking on the door.

‘What does this mean?’ asks Jim.

‘Spacesuits,’ is the urgent reply. ‘We must wear spacesuits.’

‘What?’

‘Gotta go.’

Following on after this phrase, with forensic fanfare and trumpet blare, Journo Jim is back at the office. He is a regular one-person band, a veritable orchestra, a strident jangle of story to be told; he sets forth the alarms and gets them running up and down all over his editor’s desk. Space suits he insists, but Harriet runs a finger down the guest list and says: GG.

‘Wha?’

‘Gotta go was a code. All the inmates are variations of GG.’

Calmer now, Journo Jim turned the paperwork around to see:

Garry Gold

Geraldine Gee

Gorgeous Govind

Genie Genitrix

‘This must. be made up,’ he hissed through teeth and whistled and scratched his head and took up his coffee cup and swilled it around.

‘Surely that’s your job,’ laughed the editor.

Harriet blacked in and buttressed all her staff output. She only drank water during office hours. And the drinking was out of a glass, always.

‘Day or two, not weeks,’ she concluded. ‘Something substantial, please.’ She is shooing her employee out of sight.

In The Villa they now wore grey jumpsuits, Velcro fastening, staff and guest alike wore the same. Ignatz alone wore a white jumpsuit. Everyone looked similar, although Garry Gold smelt very different. Garry Gold smelt as if he had filled his pants. Which indeed he had, several times over. And now it was his pleasure to walk along the building’s north corridor, up and down, shaking out a shitty trail. Gorgeous Govind was very upset about this. He lived next door and the neighbourly stench was creeping into his room, staining every part of his material existence. He washed down his mirror, polished his door handle, pushed cushions along the gap between grey carpet and blue-grey door. He returned to his mirror and practiced his tragic look before running down to the communal area and declaiming woe and begging for the convening of the council.

New thing this, the council. Gorgeous was the first to dare to convoke. It worked. Ignatz appeared as if pulled from a hat.

‘This is a drim,’ she delights, though only Ignatz herself appears comfortable in it. Others are coughing and shuffling, their eyes watering. This physical unease might be a consequence of Gold’s pervasive scent.

‘Now,’ Ignatz continued, ‘I have been busy with my Scribblings and Figurings. You remember how I shared this technique? Has anyone followed up on the Scribbling and Figuring rota? Remember, how we open to well-lit understanding and set to replay, looking in wonder at all that passes? Then, you recall, we turn up the illumination just a little, and look again at what feelings went into the review. After this we concentrate on just a little segment, a single feeling, and this forms the basis of our day’s Scribblings and Figurings.’

‘But I convoked a council, miss. This ain’t to do with any of that.’

‘All can come into the review, most surely.’

‘Then I might scratch about it tomorrow. What about today?’

‘What about today?

‘He stinks of crap. He spreads muck all up and down the north corridor. Why can’t I move to the south corridor?’

‘Can we talk to that my friends?’

‘South corridor is female only,’ points out Geraldine Gee. ‘North corridor is for all the others. Why doesn’t Garry just have a shower?’

‘Garry?’

‘Gold,’ he smiled. For a moment this seemed to be all the answer and the only answer he considered to be applicable. Yet he continued. ‘Gold by name, gold by nature. That is… That is to say, inner nature is gold. I just need. I need to get it out. I am waiting on true riches. Yes, waiting.’

‘Golden Goose,’ smiled Genie Genitrix,

‘All very well,’ pouted Govind, ‘only while he attempts to pass out some golden nugget, I am going to pass out from suffocation.’

He paused. He crossed his legs and arched his eyebrow, thumb lifted to touch chin, arousing the sense of canny ploy.

‘What is the line between south and north?’

‘A line between?’ Genie sensed the play.

‘Or is it a line along?’

‘The Villa has always,” repeated Geraldine, ‘always, always kept the south corridor for female residents and the north corridor for all the others.’

Govind crossed his legs in the opposite direction and lent forward, touching side of face with finger and blinking. He was trying to flutter his eyelashes, although he really had none to flutter.

Ignatz unhooked her keys and went to a door to the east of the common room. She pointed out that there are other directions apart from north and south.

‘Up and down, for instance,’ she unlocked the door and shouted upwards: ‘KARIN COULD YOU COME DOWN PLEASE!’ she shifted over to the west of the room and unlocked a second door: ‘KARL COULD YOU COME UP PLEASE!’

The council is as if cudgelled into silence, made dumb by this occurrence. What was coming to be? Footsteps, banging, shuffling – some indecision – then more footsteps. How was it that suddenly The Villa was so crowded?

Karl appeared first. His jumpsuit was grey, like theirs, but filthy; dirt rubbed smooth so as to be a graphite mirror. The room and its occupants moved as if a mirage over the rolling volumes of his legs and belly and sleeves. His hair was unkempt dreck drapery. He lifted previously chewed fingernails to his mouth and continued to masticate, a big grin creeping around the nomnomnom motion of his mouth.

‘Hello Karl,’ smiled Ignatz, ‘come and join us.’

Garry thoughtfully pulled up an extra chair.

Karin wore a white jumpsuit that had greyed with age and perpetual wear. Her hands and face were clean. Her curls were reined in by numerous clips. She walked carefully, and on surveying the meeting she stepped down the last few stairs rapidly and pulled herself a chair toward the circle. She laughed. Ignatz said it was good to hear her laugh and asked what it was that made her so happy.

‘We have not celebrated a rendezvous of this magnitude for many a moon.’

‘Many a moon,’ whispered Geraldine.

‘Ah!’ gasped Ignatz. ‘A celebration, yes!’ she clapped in a manner not to be ignored. ‘Hot chocolate please!’ And quick as you please the person who served in the kitchen hatch appeared with a trolley and on the trolley a jug of frothy hot chocolate and a wildly mismatched collection of mugs. Another cudgel blow: the occupants quietly sipped hot chocolate, and by this sugar and warmth more force fell; the shape of their world beaten and reformed beneath sweet, delicious jolts. Geraldine managed to shift around the seating to be alongside Karin. She gently allowed her knee to touch the new person’s knee. Yes, she was real.

Journo Jim was knocking.

Karl heard the thuds and, slopping chocolate on the carpet, got up and moved out the room as if to answer it. But he does not have a key Genie pointed out. And Ignatz replied that the door was not locked. This was too much for Govind. The mug he clutched, of Santa and reindeer in Bermuda shorts, sunbathing beneath the legend: Have a break. He dropped the mug. It did not break. Remnants of brown liquid spiralled out over the grey nylon expanse. Gorgeous Govind rocked back in chair, scowling. He pulled his legs up, foetal position, arms hugging his lower limbs. Ignatz took in the growing number of stains on the carpet and carefully replaced her cup back on the trolley.

‘What might it be, Govind?’

‘Doors.’

Karl came back thereabouts, large brown paper bag in his hand, stains oozing around the bottom of the bag. He dropped it on the trolley and announced he had Cut off the bastard’s head. Then he began laughing.

‘Why would you do that, Karl?’ Ignatz checked.

‘Journo, asking questions,’ spluttered Karl, immensely amused. ‘Nosey. Knew it was your birthday Doc.’

‘Did he? How lovely!’

‘And you chopped his head, for knowing that?’ checked Genie, shuffling closer to the bag but trying to keep away at the same time.

‘Yeh, yeh… Fruity fellow. Smooth white head… I did not count how many candles.’

‘That might be impolite,’ suggested Ignatz.

‘Would all the candles fit?’

‘Now you are being impolite, Karl.’ Ignatz began giggling. ‘Well, let’s share it out.’

‘Slice each,’ nodded Karin. ‘Although has anyone got a knife?’

‘YOU SEE!’ screeched Govind. ‘Doors! All evil happens at doors.

‘It looks delicious,’ Genie admitted, having overcome her dread and stood and closely looked at the contents of the bag.

Ignatz went to the kitchen hatch and returned with a bread knife and some plates. She ripped the brown paper bag apart and there was an open cardboard cakebox splodged with jam and chocolate, and in the box a cake. The white icing bore in red the word Congratulations and seven candles.

‘Four and three,’ said Geraldine.

‘Oooh,’ Karin clasped Geraldine’s hand, ‘we could not possibly presume,’ Karin’s gesture making a joke, but her fingers twisting around Geraldine’s.

‘I am not saying,’ smiled the clinician, ‘but who wants a slice?’

Jim and Ignatz looked at each other across the table. Ignatz wearing a drab institutional tunic, mark of incarceration.

‘That moment should have been our happy ending. Maybe you and I should not be speaking…’

‘Harriet would not allow anything prejudicial out into the wild, I assure you, she is ferocious.’

‘You know; I am fairly sure our paths have crossed. In my university days I attended Happenings. Body painting and bubbles, inflatables and manifestoes, that sort of thing. Harriet was there. She was pretty much instrumental in this scene.’

‘I’m speechless.’

‘Well, speechless is good.’

‘Do I speak too much?’

‘Perhaps I do. You are obviously good at research. The cake was an excellent approach. Yes, so I am sure Harriet’s history in the Happenings is not hidden. You may not have thought to look, of course.’

‘Only, we are talking about The Villa.’

‘Yes…’

‘And that day.’

‘That filthy day…yes.’

‘I met Karl.’

‘They are saying I unleashed monsters, are they not? This is outrageous. The regime had these poor creatures bolted down, terrible. Truly terrible We were not set up to either enslave or imprison.’’

‘He has chopped off heads,’ Jim checked his notes. ‘Seven.’

‘But he did not chop off your head,’ Ignatz pointed out.

‘Ah, true; only according to these timings you had not yet introduced the knife into the room.’

‘All of which is beside the point. Karl is innocent in this. It was Govind who gutted Garry.’

‘Karl escaped that day.’

‘He went for a walk.’

‘And Karin?’

‘It was love at first sight, Geraldine and Karin.’

‘Was Geraldine aware of the, um, history.’

‘They held hands. They ate cake. It was cute.’

‘Cute.’

‘Oh…well, maybe I am getting sentimental in my old age.’

‘If Govind had been allowed to move away from Garry?’

‘It was voted down in favour of Garry taking a bath.’

‘But that night he was caught straining, mm, passing out, how shall we say? Waste matter in the corridor.’

‘And Gorgeous had borrowed the knife.’

‘He is insisting that the golden egg is his now.’

‘Yes, he does so like things. Look, I know it is all a bit of a mess. My Scribbling and Figurings keep coming around to this.’

‘Coming around…to?’

‘Mess! It was, well, how shall I put it? Harriet would have approved of my little anti-hierarchical experiment, once upon a time.’

‘Who was the experiment for?’

‘That is the question, is it not? I would ask that question, very good.’

‘Who was the experiment for?’

‘This had little to do with my poor cohort. Dear sweet things, they were doing fine. Karl, he of course has a permanent chemical imbalance. Everyone else was set to resolve and move on. Karin’s hunger had abated. But the mess on the carpets? Chocolate stains, and… Honestly, it was a challenge to allow that. One does get challenged by the smallest of details, and on such occasion, one must spend a good deal of time Figuring. Drinking chocolate on the carpet and normally, of course, one does not just forget about a knife. One might suggest that aged forty three I set out to deliberately undermine myself. But let me tell you about Harriet now.’

‘I’m not sure we have time.’

‘Only, I am remembering how the cake was brought in. You collaborated with Karl on that, did you not?’

‘Collaboration is hardly the term I would use.’

‘Knowing that a cake needs a knife to cut it.’

‘Well now. If it comes to this, I must say, I was presenting the cake to you.’

‘With Karl’s help.’

‘It was not for sharing.’

‘A cake that big! Was I to eat it all by myself? Surely, one shares a cake that big.’

‘Which must perforce be cut by a knife. Anyhow…’ Jim scratched his chin, scrubbed the hair behind his ear, made a quick calculation on how calculating his interviewee may or may not be. ‘Let me just rewind the tape,’ he said. ‘I think we might start a way back here.’

‘James you are a drim, a drim and a sweetheart. Such a diligent, clean-cut young man.’

Not The End Of The World, by Annabel Banks

Their fight will begin after dinner, once the plates are in the dishwasher, the surfaces wiped. This is unavoidable. Desperate to stall—her heating works, his flatmates don’t—he potters about in her kitchen, musing aloud on his cooking technique, the need for sugar and salt, and is just remarking upon how burnt onions leave their taste in the air—if a taste can be in the air—when it lands on the roof with a wall-shaking thwop.

He stops, looks up to the corner. A new crack has appeared on the paintwork, thin as a pencilled line. The things seem to be coming more often now, despite the official figures, and her flat is on the top floor—but a crack in the plaster doesn’t mean the bricks are failing. ‘These blocks are made to last, you know.’ A pan scraped, his teacup rinsed. ‘Much better than the flimsy new-builds.’

She comes in behind him, dumps their plates. Says nothing.

‘I was thinking of buying myself, once this is all over.’

Another rumble across the roof, prompting a shiver from the wall, but no response from her.

‘Perhaps by the canal.’ Spoon, forks, knives away, their arrangement backwards to his drawer at home. ‘Vijay says if it’s proved they’re attracted to water, all his clients will leave. I could end up with a penthouse.’ He smiles, inviting her into this obvious fantasy. She knows about his credit cards, the consolidation loan.

‘You told me that already.’

‘Oh. Sorry.’

The seconds stretch out, and he realises that she doesn’t intend to speak again—not unprompted, anyway—and searches his mind for a new topic, one that will lead them away from this conversational quagmire, but draws a blank.

‘Would you like a hot chocolate?’

She makes a face. ‘God, no. I’m fine with the wine.’

‘Okay.’ He reaches for the kettle anyway, because she’s bound to change her mind if she sees him making one.

‘Actually, there’s not much milk left now. I’ll need it in the morning.’ She crouches, head hidden in one of the cupboards as she matches plastic boxes to their lids, so he can afford to send a scowl her way, double-affronted by the suggestion that he’d wasted her supplies by helping himself to two teas while she showered, plus the implication that she solely deserves whatever is left, leaving him no option but to have black coffee before work, which she knows gives him the shits.

He drops his hand, frowns again at her back. The walls shake once more, misting the air between them with plaster dust, and it occurs to him that this sort of conflict might work as foreplay for some couples, but that doesn’t work for him: he’s never been attracted to the kind of woman who relished misery, preferring a sense of emotional alignment—in bed and out—and had honestly thought that she was the same. And yet earlier, when he’d talked about wanting to strangle his landlord, whose coughing bike had woken him again at six, her reply had been a murmured, ‘but then you’d go to prison’, and he’d felt flattened by this, suspecting that, by deliberately failing to recognise a joke, she was making a statement along the lines of I misunderstood you because you are too tiresome to pay proper attention to, but you are also foolish, so I must point out the obvious flaws in your thinking.

He frowns over the sink, rinsing away the bubbles. She slams the cupboard door. Through the window he sees the darkening sky, those thick purple clouds from the east come to push the sunset away. He draws the black-out blinds, then the curtains, and—once firm in the knowledge that no slice of light can escape—touches the base of the lamp.

‘Did you check the curtains?’ Even as she speaks, she’s examining his handiwork. Once, just once, he’d left a gap, and this is the result. He chooses not to reply, but the voice inside his head is strident: everyone makes mistakes, even you, darling and then his stomach squeezes—oh no—because he has said the words out loud. Not only that, but they’d emerged in that half-vocalised mutter that obliges the listener to choose between offering no response, a position of silence that either stems from absolute power—I magnanimously disregard—or total defeat—I must not engage for my own safety—or, if the type to challenge, will trigger a sharp what? or the so-much-worse I’m sorry?, which every schoolchild knows is not an apology, oh no, but an order to stop, think, rephrase or back down, because shit’s about to get real.

So now he’s caught, waiting for her challenge, the demand to repeat what he thought was important enough to say, but not important enough to say properly, maybe feigning interest in his thought process as she asks him to unpack the psychic balancing act between what is worth saying aloud and what he wants to be heard. She will put her head to one side like a curious bird, an affectation of interest which is actually a sign of imminent predation, for hasn’t he just proved himself a scuttling bug, to be skewered on the beak of her correctly clear communication?

‘What was that?’

‘Nothing,’ he says brightly. ‘Just chatting to myself.’

‘Hmm.’ The tone of this hmm is suspicious yet weary. He keeps his head down, helping her adjust the curtain’s folds, reseal the velcro, and for a moment it is quiet between them, and he thinks that maybe they can start the evening again with a friendliness that might lead to the reset buttons of orgasm and sleep, when she says, ‘Did you make any noise on your way here?’

Make any noise? She is being ridiculous, and so he tries to illustrate this. ‘Like what, exactly? Letting off fireworks? Banging a pot with a spoon?’

‘Don’t be dense.’

‘So, tell me what you mean.’

‘I mean that you don’t seem to be taking this seriously.’

‘How?’

‘By not doing what you are supposed to do. The curtain…’

That fucking curtain. Was she ever going to let it go? ‘I said I was sorry.’

‘But it’s not only that. You don’t listen.’

‘I do.’ He stares at her, to prove that he is doing just that, right now.

‘No, you don’t. And I think you deliberately refuse to listen to me or anyone else, because’ —and here she takes a breath, as if deciding whether she wants to actually say the words in her head— ‘you’re a selfish prick who does whatever he wants.’

She’s never called him a prick before, and he feels the word trying to pierce his sense of himself, forcing him to view their conversation from an external viewpoint. Whose side would an observer take, if someone were peeking through the ceiling cracks? His, surely. He hadn’t sworn at her.

‘That’s unfair.’

‘Is it?’ Using her wrist, she pushes back the strands of hair that have fallen into her eyes. ‘You don’t think you’re doing stuff to attract them? Playing music?’ Her eyes narrow. ‘Singing?’

Oh shit. ‘There is no evidence that—’

‘Yes, there is.’ Face purpling, she hisses her words. ‘The party on that balcony. That man with the phone.’

‘That’s not evidence.’ He turns to busy himself with the table, brushing loose grains of salt into the carpet. ‘Look, I get you’re upset, but I don’t feel like it’s my fault you swallow every crazy theory out there.’

She pauses, processing this, and he can tell the exact moment she allows herself to tip over into anger, because she gets so very still everywhere except her eyes, which, oddly enough, call to mind the crackle of burning twigs.

‘So, just to be clear,’ she says, ‘my complaints, my concerns, all the stuff we’ve been talking about these last three weeks, are down to a failure in my critical faculties?’

Oh shit, he thinks again. Out loud: ‘I never said that.’

She touches the tabletop, touches her glass, and when she speaks it’s with the air and intonation of someone offering him a coffee. ‘You think I’m stupid?’

‘I certainly never said that.’

They glare at each other, and for a second he feels them teetering on the edge of a different kind of fight—one that would break open this argument’s chrysalis to have it emerge new, unrecognisable—when another of the things lands on the building with a great thud and starts rolling around on the roof.

It must be a big one, and yet the clatter of tiles shifting under its rubbery skin is not the worst sound he can hear, oh no, for that is the flobble or blobble it makes as it moves, a glooping sound that brings to mind the water balloons of his childhood, only deeper, like they were filled not with water from the tap, but with paint or unrefined oil, and not like that anyway, but quite different, and yet this is the only way he can make sense of what he is hearing. He hears other sounds too, as they roll—an excited guinea-pig’s whoops and chuckles, a washing machine with an unbalanced load, rocking and banging as it spins.

They both stare up at the ceiling.

‘Will it hold?’ she says.

‘Of course,’ he replies. ‘Vijay told me that these post-war builds were made with proper materials. Not like Bristol.’

She closes her eyes, and he regrets bringing up those images.

Another thud. More rolling, bubbling sounds, louder now. It must be overhead, squidging itself as it moves around, the part of it that touches the slate slightly flattened, as though it has a slow puncture.

The roof seems to be taking the weight. ‘Soon be gone,’ he murmurs.

‘You don’t know that.’

‘There’s no reason for it to hang around. Someone will drive past soon, and it will bounce off after the headlights.’

She throws him a look of disgust. ‘And what about the people in the car?’

He could reply that these imaginary citizens would be fine as soon as they hit ten miles an hour, but she knows that, so instead he takes her hand, the fingers cold and stiff, and kneads and warms them with his own until she draws away.

‘Just go,’ she whispers. He’s not sure if she is addressing him or the grey intruder on the roof. ‘I can’t take any more.’

He opens his mouth to rebut this, then pauses. How would he be able to tell whether she was telling the truth, or merely being theatrical? Maybe she

take more, but he doesn’t want to be the one to test the weight of her emotional ceiling. Deciding that she needs a moment, he picks up their wine glasses and uses his elbow to switch on the kitchen light, planning a splash more for each, and is just deciding if maybe, as he hands her the glass, he should touch the top of her head in a tender cease-fire, when the window behind him explodes inwards, showering the floor with jagged shards of glass.

They both leap, her forwards, him back, and so come to rest side-by-side, as the thing bulbs its way inside the room. ‘Get the fuck out,’ she screams, catching up the scissors that hang from a magnetic hook on the fridge to poke at the grey, stretched-silk skin. ‘Get away from here!’ And as he moves behind her in an unseen gesture of support, the smell hits him, that hot-fat smell which always reminds him of the beer garden where they went on their second date, that had looked perfect in the pictures but—disaster—had been built next to the kitchen vents, and thus reeked of thrice-fried chips and oil-dunked bean burgers, and where they had both soldiered on, neither wanting to appear an unattractive fusspot, tiresome in demands for olfactory purity wherever they dine, until an older American couple on the table next to them had exited, loudly expressing their revulsion, and he’d met her gaze with amused agreement before following them out.

‘Get back,’ he shouts, trying to take the scissors from her. Spinning, she shifts her grip and attacks the thing over-armed with a frenzied stabbing that has no effect at all, a toothpick to a tyre, until eventually it withdraws from the window and rolls completely off the corner of the block, the both of them so still as they listen to the second of silence, the gravelly crunch, and the sound of it wobbling around the corner in the direction of the main road.

‘It’s gone,’ he says, and turns in time to witness the rolling of her eyes.

‘But why did it come in the first place? The window was blacked out.’

‘It wasn’t trying to hurt us, I think. Just passing over. The glass couldn’t take the weight.’

‘Well, aren’t I lucky.’ She waves the scissors towards the mess on the floor. ‘So now there’s this. On top of all this shit, I have to find the money for a new window.’

‘Don’t worry,’ he says. After a moment’s hesitation, he steps forward to take her by the shoulders, with a pause just before his hands come to rest, waiting for that shake of her head. ‘I can pay half.’

But she neither rejects him, nor softens under his touch. Instead, she stands there, teeth working her bottom lip, eyes on his. ‘You don’t need to do that,’ she murmurs, and he knows the it’s my flat, my private home, you are here on sufferance, and what money have you got anyway might be unspoken, but that doesn’t stop it being real, and anyway, he abruptly realises, the broken window might only be the start of the evening’s events—he’s seen the pictures from Glasgow, the flattened school in Milan—so volunteering to pay towards the cost of any damages before he knew their true extent would be unwise. There’s nothing to do but nod, drop his hands, and move back in an almost ceremonial fashion, like the measured step of a graduate or newly arisen knight. ‘We can talk about it later.’

She shrugs.

‘Do you have anything to cover the window?’

‘Nothing dark enough.’ Another shrug. ‘A blanket, I suppose.’

‘Great. I’ll hang it over the hole and we can wedge a pillow against the bottom of the door to make sure.’

She fetches the blanket—more a quilt, it turns out: steel-grey, slippery, difficult to wrangle—and helps him loop it over the curtain rail, securing the fold with wooden pegs from under the sink. They work in darkness, her face near his armpit, her breasts at his back, and the result is clumsy but serviceable. When they have retreated into the living room, he feels safe enough to bring the conversation back to better things, and is searching his mind for a topic when she speaks.

‘Do you think it will be back?’

‘Probably not.’ She’s upset, of course. The window. The smell. ‘It’s off the building now.’

‘Okay.’ Stooping, she adjusts the pillow by the closed kitchen door. ‘As long as you’ll be safe.’

‘Safe?’ he says, before he can stop himself.

‘On your way home.’ She stands and, without looking, puts a toe over a shard of window glass, shifts her weight and crunches it underfoot, and he knows that she means it, because otherwise she would have wanted to fight for longer, raise their voices and wring the misery from each other like water from a dishcloth, more, and again, until the cloth is dry, the palms of their hands sore, and then even more still, until there was nothing left but to collapse into each other and whisper words like sorry, forgive, try.

There was none of this now, and—as surely as the thing outside would be back—he knew they were done. The realisation made his stomach lurch, but at least it was a familiar sickness, one that he knows will end. Best to start the process right away. He’ll gather the few items left here over the last months, kiss her a firm goodbye and ramble back to his grubby room, singing songs from bands he’d liked when he was still at school.

MIRLive : Dec 8th 2023

MIR (The Mechanics Institute Review) will be holding its first live event of the academic year on Friday, December 8th (Keynes Library, Gordon Square 6pm). The event will include eight readings, including one from Wes Brown (Programme Director of the MA in Creative Writing and the author of Breaking Kayfabe) and six from current Birkbeck BA and MA creative writing students.

If you’re a current student interested in reading at the event, please send a piece of prose (up to 1,500 words) or two poems to mironlineeditor@gmail.com. Submissions should have ‘MIR Live Submission’ as the subject line of the email. Please include your name, the title(s) of your piece(s), and a contact email address at the top of the first page.

We look forward to reading your work!

The MIR Live team

Featured Speakers

Wes Brown

Wes Brown is the author of Breaking Kayfabe, an autofictional account of his time as a champion pro wrestler. He was awarded a CHASE Scholarship to research Narrative Non-Fiction at the University of Kent, founded the publishing press Dead Ink Books and his stories, reviews and essays have appeared in publications including New Humanist, The Critic, The Times Literary Supplement, The Real Story, Literary Review, Litro, the Mechanic’s Institute Review and 3:AM Magazine. He is the Programme Director of the MAs in Creative Writing and Creative Writing & Contemporary Studies at Birkbeck.

Elsa Court

Elsa Court is a writer and translator based in London. Her short stories have appeared in American Short Fiction, The Brixton Review of Books, The London Magazine, The Tangerine, and Worms, and she is the recipient of a 2023 International Literary Seminars + Fence Reader’s Choice Award in the short fiction category. Her essays on contemporary literature have featured in Granta, The White Review, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Times Literary Supplement, among others. She is an Associate Lecturer in Creative Writing at Birkbeck, and a Lecturer in French at the University of Oxford.

Elsa Court is a writer and translator based in London. Her short stories have appeared in American Short Fiction, The Brixton Review of Books, The London Magazine, The Tangerine, and Worms, and she is the recipient of a 2023 International Literary Seminars + Fence Reader’s Choice Award in the short fiction category. Her essays on contemporary literature have featured in Granta, The White Review, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Times Literary Supplement, among others. She is an Associate Lecturer in Creative Writing at Birkbeck, and a Lecturer in French at the University of Oxford.

Dead Mouse, by Charlotte Turnbull

When we finally found it in the corner of the downstairs loo – the dead mouse – the children covered their noses with their sleeves and refused to eat breakfast in the kitchen because of an alleged lingering smell. They leaned into the drama. What child doesn’t relish revulsion and swoon? They defined themselves against something – it, or us – and found a purpose, a unity, that morning.

There are maggots, my husband said, taking rubber gloves from below the sink: he was ready to get dirty, but not too dirty. How long has there been a smell?

A few months, maybe longer, I said, confident and complicit in our marital myth that my larger nose led to engorged nasal cavities, ergo a heightened olfactory sensitivity, along with all my other heightened sensitivities: lively digestion, easy fatigue, wet flushes.

A few months, maybe longer, he repeated, staring at my belly.

In the kitchen, the children began to mutter – that kind of bored mutter that builds to skirmish, then civil unrest – so I led them, their plates of toast stacked up one arm, into the living room, to the TV, and closed the door on it. The smell.

*

The children ate their breakfast but refused to leave the living room until I opened the window so they could climb straight into the garden.

The eldest went first, then climbed back into the house seeing my husband upend a plastic bag into the rhododendrons. Retreat, she shouted. The little one backed away, accommodating and grateful not to be in charge.

We are trapped, the eldest shouted from the window at her father, our home is a mortuary.

I was impressed with the eldest’s vocabulary, wondering if I had not spoken to her properly for a while, when the little one began to cry from a deeper sense than the rest of us about what was at stake.

On the lawn, my husband stuck his arms out and lurched about like a zombie, delivering the wrong punchline to the right joke, and I considered whether another coffee would kick me through the rest of the day into the familiar sleepless night.

I took the little one onto my lap and kissed her forehead, but she pulled away and fell to her knees, officiating the marriage of two Sylvanian animals in one smooth, quick movement instead of putting her arms around me: instead of pulling my t-shirt to palpitate my breast.

*

If we had pretended – if my husband and I had frowned at each other, turned the corners of our mouths down, looking from side-to-side, avoiding the hard truth of the eye, the grey frame of our faces – could we not have just left it? Could we not have ignored the smell?

I didn’t tell the children that a rotting mouse smells exactly like an old, used tampon. I didn’t want an old, used tampon to be their first experience of death.

Charlotte’s fiction made the Galley Beggars Story Prize long-list 2023 and the Caledonia Prize long-list 2022. She is also published in Litro, The McNeese Review, New England Review, Denver Quarterly and as a chapbook with Nightjar Press..

.

Review: Sea of Tranquility by Emily St. John Mandel

Dan Crute reviews Sea Of Tranquility by Emily St. John Mandel (Pan Macmillan)

Review: Singapore by Eva Aldea

Katy Severson reviews Singapore, by Eva Aldea, published by Holland House Books.

In Eva Aldea’s debut novel, Singapore is hot and humid, tense, sterile and slow. There are snakes and crabs, expat housewives with Filipina maids. At the centre of this, there is an unnamed female protagonist who vehemently resents her life abroad. She hates the humid heat, struggles to relate to the fellow expats in her circle, and finds solace, it seems, through violent fantasies of murdering the people around her.

At its core, ‘Singapore’ is an account of a woman trapped by her life as a housewife in a foreign country, and an exploration of the beastly depths of the human brain when left alone to stew. It’s also about the complicated socio-political landscape and dripping heat of Singapore itself. In the background of the protagonist’s personal story is an exploration of class tensions, privilege and colonialism. She is almost painfully aware of her privilege, and she both resents the class system in Singapore and enjoys the benefits it offers her. Singapore, a nation where ‘not all cultures are treated equal all the time’, is called into question—and we’re left meditating on the ethics of capitalism and the impact of British colonialism.

The writing itself is precisely detailed and cinematic, like a calculated screenplay in which every moment or object feels intentional and significant to the story. We see our protagonist taking coffee beans from the freezer, removing a clothes pin, replacing it. We watch her navigate the packaged rice aisle in a supermarket, picking up each variety and putting it back on the shelf. She moves something from a desk to another desk to the kitchen counter; she adjusts the temperature of the fridge. And we find ourselves wondering where these moments might lead, constantly kept on our toes. These details also have a way of stretching time and rendering an eerie, creeping slowness to the text that’s punctuated by consistent references to violence and death.

There are venomous snakes and fighting fish. There is the chopping and grinding of coffee beans, the slicing of liver and lungs. Our protagonist sees ‘corpses’ at a yoga class and realises that she likes chopping meat and scooping aubergine flesh, ‘fascinated by these things that once were alive’, interested in ‘the thrill of the hunt’—until it turns into elaborate fantasies of murder. At points, the descriptions are so detailed and elaborate that it’s hard to tell what’s real and what’s projected. Has she actually murdered the maid? Is she actually keeping a body in the boot of her car? Or are her fantasies simply that calculated, a deeply analysis of what she’d have to do in each instance to get away with it? I’m not convinced we’re meant to know. The book becomes a blurred reality and a manifestation of her manic thoughts.

There are times when the details feel over-explained, the scenes so mundane and so slow that it risks boring the reader. But that, I think, is the sheer brilliance of the writing. Aldea forces us to endure the boredom of her protagonist and the brutality of her thoughts as if we’re right there with her. These mundane details invite us into the confines of the protagonist’s brain in ways few fiction texts do. We see her question whether she should kill herself, watch her spill hot water on herself just for the drama of going to the doctor. And the result, somehow, is a likeable character: someone painfully self-aware and tortured by her day-to-day and someone worth rooting for, even despite her murderous fantasies. The reader is so intimately intertwined with the text that we can feel the muggy heat, the long and languid days spent alone, and we feel trapped right there with her. In a way, I too went mad as I read it.

This is a book is for anyone curious about exploring the absurdities of the human brain and the animalistic tendencies that exist within us all. It allows a rare look inside a character’s intrusive thoughts—the kinds of thoughts that few authors are bold enough to put on the page. In an article on Books By Women, Aldea credits ‘discomfort and boredom’ as the driving force behind her writing, recalling her own experience living abroad in Singapore and the complicated feelings that arose from it. I like the idea that this novel serves as a means of exploring the depths of one’s brain in ways we often don’t let ourselves. One’s anger and frustration taken to extremes. One’s beastly nature on full, unabashed display.

Katy Severson is a writer and chef based in London. Her work has appeared in Huffington Post, Cherry Bombe, Bon Appetit, Fifty Grande and others with a focus on social and environmental justice issues in food. She completed her MA in Creative Writing from Birkbeck University in 2023.

Moon, by Jo Stones

For the third time this morning Mary looks through all the spaces,

turns her head left, right, imperceptibly

alert

then tilts forward, bending herself in half,

walks, folded, with tiny, quick steps,

searching along the edge of skirting,

the floor,

under a wooden chair.

She pulls herself upright, stands,

sighs,

then bends herself around objects, feels pieces of furniture, cushions,

peers inside a dusty glass vase,

flicks books

shakes a bottle,

moves her hand along surface after surface.

Inch by inch, Mary scrutinises.

– There’s not enough time for this.

Her left ear whistles,

her head fills with a noise not unlike untuned radio stations, not calming.

No.

Mary looks at the coat-hooks, feels around the last jacket she wore, her fingers digging in the pockets.

Fluff, coin,

the keys aren’t there, she knew that.

Stand, very still, collect.

Mary closes her eyes, slowly breathes in

through her nose,

and out through the small opening of her lips.

The key to calm is breathing,

but the key to her flat is missing.

She opens her eyes, swallows then, turning around, with miniscule movements, steps forward, looks back, forward …

And again, through the flat.

‘Retrace every step,’

from the front door and into the kitchen.

Mary touches all the hooks that she recently screwed to the back of the door,

a place for storing keys.

She walks from the kitchen to the sitting room.

Mary drops her body softly to the floor and rolls over, lies on her back.

No.

Time.

Mary sits up, gets on to her knees and crawls across the room on all fours, her fingers widespread, star-like,

sweeping across the carpet,

windscreen wipers.

“You’d lose your head if it wasn’t screwed on so tight.”

Mary pulls herself back up to standing,

pushes away the image of a screw-on head,

deleted from her mind.

Not a time for an annoying turn of phrase,

… can I pick your brains?

Why do people say such things?

Worst of all is saying someone is ‘mad,’ as if they themselves are not …

who can measure madness versus not?

“Retrace your steps,”

it’s what she always says,

said …

to Ben.

He had loved her, or seemed to …

And then he also hated her.

Which is why he left, or she asked him to leave, somewhere in between that mutual partition,

Ben forever angered by suggestions such as tracing steps …

“But it really does work,” Mary would say …

and, if he wasn’t too enraged, she might carry on …

“… it’s an extra sense we have when our minds can’t remember. Inside us we do actually know where we have put things, it’s amazing, our bodies remember everything!”

Her own advice now.

It will work, it does work.

Retrace your steps.

Mary revisits herself arriving home yesterday, unlocking the door,

the pockets in the clothes she wore …

She lifts her arms out and up high, to widen her lung capacity,

to help her breathe.

She will remember.

She lies on her back, closes her eyes, and imagines …

walking,

a miniature Mary, walking through a map, a set design of the flat …

“Fuck.”

She can’t see the moment.

The moment she placed the keys …

Mary pulls herself up and stands, not able to see much, no proper focus,

the veins inside her temples pump,

a sense of nausea …

actual nausea,

dry throat, tongue, teeth.

This time she’s going to fall,

fail.

Moon will be waiting at the train station, cold.

Sweet as he is, hopeful at first …

searching the faces of disembarking people …

She lets him down.

She will not,

not today.

That isn’t who Mary wants to be.

You’re on your own Mary.

So was Moon. On his own.

There was a time when he had lived like a wild man, on the edges of roads, railway tracks, in prisons, shelters.

Moon would find his way back, like a cat, to Mary.

He would ask for money, tobacco, food …

and be off again, into the dark night.

Mary lowers herself back to her knees, eyes open, crawls like a predatory cat, across the living room carpet once more.

Persian.

Deepest indigo, artery red, clotted cream, a soft sky blue … touch of dusky pink on the petals of the central flower.

Dyed, thick, hand-woven.

Mary stretches herself out on the carpet, face down, smells the wool.

Kav and Patena gave her this carpet,

Iranian friends, she only knew them for a year or so.

They moved cities, lost touch.

Good, organised, generous people, they helped Mary out when she first moved into the flat.

“I have many rugs, you need a rug, please, take it,” said Patena.

It was a Saturday afternoon. Patena turned up, out of the blue, with her husband, Kav. They walked up the steps, one behind the other, straight through the door into Mary’s new flat, the huge rug, rolled up and over both their shoulders like a prize stag.

The rug unfolded across the bare wooden floor, magic.

If Patena had a brother like Moon, she would always be on time for him, and bring him rugs.

Keys.

They must be hiding in the carpet pattern,

They fell from her bag, yes, they are here.

Mary urges the carpet to surrender them.

Now’s not the time…

and

… nothing.

“Fuck.”

She’ll miss the train.

Bad sister, did she do this on purpose?

not caring.

Is that what Moon will think?

and his carers, they will think that.

Is that narcissism, to worry what they think?

Does she care enough about her brother?

or does she care what her brother’s carers will think?

A swelling sensation fills her ears, as if with too much air …

she can’t locate it,

not exactly.

Every part of her senses feels wrong …

breathe.

It happens, this.

Mary knows … and she can’t stop it,

and then she can.

She’s not mad.

No.

If Ben did ever love her, he didn’t love this.

He would grow angry. He would say she was mad.

Anyway, he’s gone now. So that’s that.

Mary sits up cross-legged in the middle of the rug.

That’s all over now,

like the shift of a scene in a film, wipe.

Mary pulls herself up,

lifts her bag from the chair where she’d placed it, all packed, ready to leave an hour ago

when she was calm

before she knew she didn’t have her keys.

Already checked; the keys are not in the bag.

Check again.

Mary tips the bag out on to the kitchen counter, willing the hard sound of brass Chubb on wood

… if only…

She puts everything back …

the navy tissue-wrapped gift; a new phone for Moon’s birthday.

Moon loves gadgets.

Her wallet; debit, credit, cash …

She checks the lid is properly on a pen, drops that back in the bag,

flicks open her notebook; the keys are not hidden inside that either…

hand sanitizer, hand cream …mask.

And her mobile and charger, that’s all.

Scrunching her eyes tight, nose wrinkled, like Dorothy wishing, heel-clicking,

she psychic messages her keys …

come on!

it’s an inanimate object.

That can work.

Mary’s done that before,

knows there’s a cosmic possibility the keys will appear.

Moon will be upset if she’s late, there’s only one train an hour.

He’ll think she didn’t want to come.

Did she?

Moon would never miss a train.

Moon is reset and now lives as perfect order personified,

always on time.

Mary feels hot, clammy, pale…

Moon used to tell her that her lateness could increase his psychosis.

“My stress levels go up…” he’d say.

Mary tries not to panic,

or cry.

That was before mobile phones and texts,

at least there is that now.

She pushes her bag across the table, lays her head on her hands.

Be there for him.

Be more. Be the rock,

Be …

normal.

A swollen sounds fills Mary’s ears again.

… there… it’s there, hovering in the space between her eardrums … temples, throat …

No.

Go away.

‘Breathe,’

Mary stands, paces around the small kitchen to …

kettle.

A cup of tea with sugar, help …

as it would a person who’s been in a car accident.

Breathe,

she can breathe

“Yes”

Mary fills the kettle, it boils,

she sits at the table,

stares at the brown, incomplete circular mark from a hot cup, no coasters.

Mary drinks the sweet tea, feels better

breathing settled,

inner ears clear.

No big breaths into brown paper bags, not for her.

Restoration: Mary is a rock

… in a forest, patterns spread across its body,

wiggly lines of whitish, Verdigris lichen,

fungi meeting moss, a beautiful harmonious marriage.

Stop

…riddles.

It’s time, come on, find the keys now.

He will have prepared,

impeccably dressed, he will check his watch often.

Mary should call, tell him she’s late.

Text, that’ll be easier…

– Hi Moon, slight delay, don’t worry, I’ll sort it.

He replies:

– Okay May

Moon started calling himself Moon and Mary ‘May’ when they were teenagers.

It stuck, just between them.

Outside chirrups from tits, blackbird, finches, a green parrot squeak, winter’s end.

Cars hum from the main road.

Mary is breathing, her inner ear, free, her head clear.

She walks into the middle of her living room, the plain tree swaying outside her window, the linen curtains flow back and forth from the window to the chalk white walls.

Mary closes the window, everything settles, all seems clear.

She hopes Moon won’t be sitting on the station platform,

Moon didn’t used to come and meet her from the train.

He’d be waiting, perhaps sitting on the wall, or standing, outside the door of his sheltered home. He’d know what time she was due to arrive, would be looking out for her as she came up the hill from the station.

Sometimes she’d see him stand in the middle of the road, waving his arms, huge waves, as if she was a plane that needed help landing in the fog.

Now he has his own flat. Independent living, home comforts.

A framed poster hangs on the living room wall:

“Life is what happens while you’re making other plans.”

“It’s a quote from John Lennon,” Moons says, almost every time she visits.

He loves that he knows this. He agrees with Lennon.

Nothing much happens for Moon except ‘life.’

Once a great deal happened.

Mary was still at school. He’d run away from home, or had he been thrown out?

He barely ever came back after that, or he wasn’t allowed.

If he did turn up it was most often at night. He’d call up to Mary’s bedroom window to ask for money and cigarettes, then he’d disappear. And he did that for over a year, then he was missing for a long time.

Even more stick-thin than before, and extremely leather-tanned and filthy, Moon was sat on the front steps one day when Mary got home from school.

Ping-pong eyes, a shock on his face with its hollow cheeks.

“Bath time,” Mary sang, joking nervously.

Moon followed Mary inside the house, around the kitchen, then to her room and back to the kitchen.

He stared at her continuously.

“You’ve got a purple aura,” he said.

His matted hair stood up; his scabbed, bare feet stank.

Maggie, their father’s girlfriend, got back from shopping. She took one look, laughed meanly at the state of him, waving the air regarding the smell.

“Your brother’s a nutter,” she said to Mary, barely suppressing a mean smirk then,

“I’m going out, your father can deal with this,” leaving them both in the kitchen.

“What happened?” Mary asked Moon.

Moon looked like he’d cry so Mary made tea.

Hearts broke.

Home from work, Dad was sad.

He turned, long enough to give Mary a strained, smile.

“Michael, son, let’s go in the front room and have a chat, eh?”

Only Mary called him Moon. Everyone else called him ‘Michael.’

Mary crawled to a place on the hall landing where she could just see through the jar of the door to the front room.

Moon, sitting on the couch beside their dad. Awkward, sweaty, mumbling,

and then Dad’s low voice,

“Have you taken any drugs, son?”

Moon’s head hanging.

Bless me father for I have sinned.

Silent, enormous teardrops falling,

Moon tears,

stunned,

silent as night.

Mary huddled on the landing as it grew dark, endlessly sobbed into her knees.

Keys.

Mary will find them.

She will leave, and get the next train, arrive, and smile.

What Mary really wants is not to be a rock, Mary wants a rock.

Dad found it hard to be a rock. He wanted to be a rock, then he died.

In Moon’s clockwork life, he has rocks, paid capable, caring, calm rocks.

Mary’s not his rock. Mary is chaos and causes psychosis.

…find the keys!

Mary was the well one … able,

expected not to lose things like keys, to arrive on time.

It was a secret. Moon’s breakdown.

Moon went to hospital. Mary went to school.

She hid in a dark cupboard.

There were damp mops standing with their soggy heads up, buckets, brooms and Mary, solitary confined, crying in isolation.

As if Moon had died. This one who looked a bit like him, is not him, where is he?

… Come on!

Keys, Keys.

stop going back over tracks,

awakening pain.

Moon’s rebuilt now,

sweet, peaceful, medicated, well.

Where are the keys?

Retracing, again, the steps she took the night before …this has become so boring.

Time – 9.20 am.

Too late for the 9.27

Mary texts Moon again:

– I’m running late, so sorry … Next train, promise!

– Okay May (thumbs up emoji)

That’s a good sign, the thumbs up.

Mary relaxes a little.

– Sorry Bro, just can’t find my keys.

– Don’t worry, May, life is what happens when you’re making other plans

– Ha, yes! So it is!

– I’ll be waiting for you, May (smiley face emoji)

– Thanks, don’t come to the station though.

– I’m already at the station May.

Shit!

-Okay, sorry! Mary replies.

– Don’t worry. I’m used to it by now, May. You’re always late. I’ve brought my book. I’m reading Lord of The Rings. It’s really good. I don’t mind waiting for you.

Moon speaks to her as if he’s her psychiatrist,

nods, says ‘mmm.’

And he uses her name, a lot.

Mary’s in the room, her kitchen. No more panic.

She leans against the tall fridge; its magnets fall from the door.

She kneels to pick them up.

Partly obscured by the bottom of the fridge, is the Lancashire red rose keyring that once belonged to their dad. He’d bought it on a pilgrimage of his childhood, back in the eighties, she’d kept it when he died; uses it for her keys now,

her door keys.

She picks them up.

“You heard me.”

Jo Stones was born and grew up in Sheffield, then New Zealand and then South London. Aside from ‘Moon’ her non-fiction story, ‘Lotus Instructions’ was published in Wasafiri magazine, 2016. She is a graduate from Birkbeck’s MACW, as well as University of Westminster’s BA in film, where she wrote short screenplays. Before that she was in three quite dreadful bands where she wrote the songs. She is currently working a novel, usually at the crack of dawn before starting work in her role as an archive producer for documentary films.

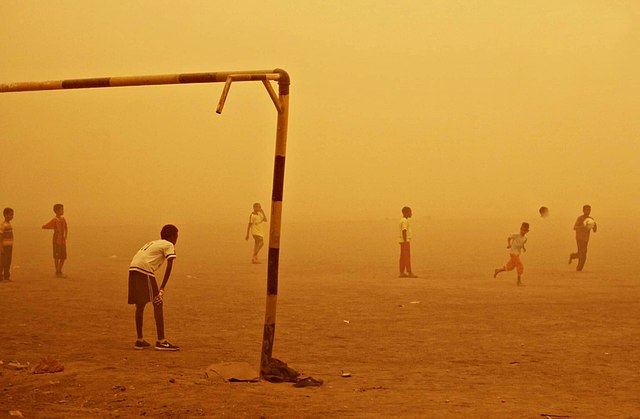

The Dead Good Footballer, by Tarina Marsac

The Dead Good Footballer: Audio

CAST:

Jack — Sacha Marsac

Claire, Jack’s Mum — Grace Robson

Sam, Jack’s Dad — Julian Jones

Tom, Jack’s Brother — Max Marsac

Lizzie, Jack’s Sister — Florence Marsac

Daphne Beauchamp — Alicia Marsac

Recorded by Christian Marsac at The Safe Room

Jack

30 October 2018

I love playing football. In a different life, I would have been a professional football player. In that life, I would have been good enough to be a professional football player. I would have played for Arsenal and England. However, football is not how I earn my living. I’m a delivery driver with Hermes—and let me tell you—I get a lot of abuse in my job. Customers get annoyed because they’ve waited in for hours. Don’t get me wrong; I get where they’re coming from, so I always give them a smile and a hello. But they can be bloody rude back. Still, none of that matters much because every weekend and one night a week, I get to play football. Mum and Dad are coming to watch tonight’s match. I’m going to tell them I’m getting back with Daphne Beauchamp.

I’m on fire tonight. I’ve scored two goals, one of which I’m incredibly proud of—even if I say so myself.

God, I feel a bit odd. My chest is running out of breath—which is not like me at all. I’m super fit. I eat well. I don’t over-indulge in alcohol and never do drugs. To tell the truth, I’m a bit of a body-temple kind of man. And I’ve watched some of my friends—Mark Wainwright and Robbie Higgleston in particular—their lives ruined with the stuff they’re smoking and snorting.

I carry on running. My breath will catch up with me. I just need to focus. The ball is heading my way. I run to intercept—the world has turned blurry. Everything is in slow motion.

I feel odd.

Weird.

Oddly weird.

Weirdly good.

I want to kick my leg high, and my right foot wants to point, to flick the ball toward Geoff Berkey on the left side. But I’m falling backwards. The ball passes over me. My ears are whooshing. My heart is banging in my chest.

Why am I on the ground?

I’m trying to stand up, but the weight on my belly won’t let me. I can’t open my eyes to see who is sitting on me—stopping me from playing. I wonder if it’s Brian Williamson, that six-foot-two-inch wing-back on the other team. He’s always had a beef with me.

Why can’t I open my eyes?

Something is pulling me up. I can feel breath on my face, hands on my body, pumping, and rhythmic pressure on my chest.

I feel light.

Other-worldly.

I don’t understand what’s happening.

I am not afraid.

I look down at the football pitch. People are crowding around me. I’m lying on the ground, yet I can see myself from up here. I’m shouting, but no one is listening. They can’t hear me.

I’m going up.

I can still see myself lying there. Several people are there, and someone has a defibrillator. I had training for that—along with a couple of team members—on what to do, how to use it, and when to use it—I never had to, thank goodness.

I can see it’s too late for me. Looking down there, I know I’m not going back. I can see Mum and Dad screaming. I call them to let them know I’m okay. They can’t hear me.

I can’t help them.

They’re on their own now.

I’m getting lighter.

I’m a marionette, and my puppet master is pulling my strings. Mum and Dad are disappearing, my teammates, the crowd—they are all going. I’m drifting but at speed—upwards, and everything feels good. I no longer mind that Daphne Beauchamp slept with Daniel Frost. I no longer care that Tom steals my football boots, thinking if he wears them, he’ll be as good a footballer as me. And my tooth that’s been giving me gyp for what seems like forever has stopped hurting.

I’m lighter.

I’m soaring upwards like the freest of birds.

This is amazing

I want to tell the world how amazing this feels—except I don’t care. I’m just enjoying the ride.

I am not afraid—not even a bit.

*

Claire, Jack’s Mum

30 October 2018

It’s freezing outside, and I want to stay home, change into my pyjamas, wrap up with a fleecy blanket and watch the final of the Bake-Off. But I promised Jack that his Dad and I would watch him play football tonight. After all those years of sitting on the sidelines every weekend winter morning, I feel I’ve done my bit. Still, I suppose it’s not that often he asks anything of us now. He’s almost thirty, left home a few years back, and is independent. I miss being part of his daily life.

I’m wearing layers of merino wool and cashmere blend. I’m glad I’ve still got Sally Markham’s Canada Goose coat—I must give that back to her soon. Sam is not as wrapped up as me. Why doesn’t he feel the cold?

Jack is playing his favourite position. He is good. I had forgotten just how good. Shame he didn’t make the grade as a professional. He tried so hard, trained so hard, and worked so hard. Still, at least he gets to play every week. It gives him a break from his day job—people can be rude to delivery drivers.

He scores. It’s a great goal. Even I can see that. The team gather around him, hugging him, cheering him. He looks taller. The game starts again, and he’s off like a rocket. No one can catch him, touch him. WOW! He’s only gone and scored again. I am so glad I didn’t bail out. My nose is icy and running, but I don’t care. This is so exciting. Everyone is watching Jack, including the other team. That big bugger, whats-his-name, Brian something-or-other? He’s very close to Jack—too close. The ball is flying through the air, and I can see Jack and Brian going for it.

What happened? Jack’s fallen.

I don’t think that Brian bloke pushed him, but maybe he did. The ball is still in play, but Jack is on the ground.

Why isn’t he getting up?

My heart is pounding.

Something is wrong.

I feel very hot in my layers. I undo the zip on my big coat. I throw my gloves off. My insides are shaking, not from the cold but something else, much scarier. I don’t know what it is.

Jack is still on the ground, and Coach is near him. People are pounding on Jack’s chest. I’m running. I need to get to my boy. Sam is running a few steps ahead of me, and I feel cross that he’ll get there before me. Somebody has brought a defibrillator.

Why?

There is not a sound except the roar in my ears. Only it isn’t in my ears. It’s coming from me—from deep inside me. I scream, and I scream. My knees are weak, and they stop supporting my weight. I fall next to my big, nearly thirty-year-old baby. Sam is next to me.

I’m trying to pick you up, Jack. You’re too heavy. Your Dad helps me. And we rock you, just like we did when you were a little boy and scared of the monsters hiding under your bed.

I remember pushing you out of my body Jack. Those hours of labour, how much it hurt. And the last push when you fell out of me and into the safe arms of the midwife.

I remember her placing you on my saggy belly, and you opened your eyes, looked at me, and everything in the world melted away except us. I remember your Dad crying. He was so pleased to have a son.

I remember knowing how perfect feels.

You’ve gone, Jack.

I can feel it.

I want to look up to see where you are, but I’m afraid in case I don’t see you. In case I do.

I am so afraid.

*

Sam, Jack’s Dad

30 October 2018

Jack is playing footy tonight, and the missus and I are going to watch him. It’s been a while since he wanted us on the sidelines. When I think of all the weekends we spent in the cold, it’s hard to believe where that time has gone. He’ll be 30 soon. I need to warm the car up for Claire. I’ve had a bit of trouble with the starter motor recently. It’s bloody cold tonight. I’m hoping we don’t break down. I can imagine what Claire would say, and she’s not that happy about going out tonight. The bloody Bake-Off final is on, and she’s been rooting for that Rahul bloke all along. Personally, I find him a bit sappy.

The car is running, warm enough for Claire. I wish she’d hurry up. I don’t want to be late. There is a real bite to the air tonight. I wonder if I should have worn a thicker jumper.

Oh my God! Claire looks like she’s going on an arctic expedition. Where on earth did she get that coat? Still, at least she’ll not complain about being cold!

I’m excited about tonight’s match. Jack has always been a good footballer. When he was a lad, he wanted to be a professional. He was nutty about Arsenal and England–of course. He was good too. A couple of scouts sniffed around. He trialled for various youth clubs and ended up at Crystal Palace, but he didn’t make the final cut. I’m pleased he hasn’t given up, though. It keeps him fit. And that day job of his must drive him mad, the traffic in London is awful, and some people can be very rude to Hermes drivers. What is that about? He does his job well; they get their parcels—’ get over yerselves.’

The match is going well. Jack scores the first goal. It’s a cracker of a goal, too. His teammates are proper all over him. There he goes again, flying down that field— he’s only gone and scored again! I reckon he’ll get ‘Man of the Match’.

Some of the players on the other side are big buggers, but they’re not playing too dirty. I’m glad about that. Bloody hell, the ball is flying through the air. Jack is going for it along with that 6’2 monster Brian whatever his name is. I hope he doesn’t knock ‘im down. Jack would feel that good and proper.

The ball is still in play, but Jack is on the ground.

What’s going on?

He wasn’t pushed—I’m sure of it.

Something feels off. I’m looking at Claire. Her face is off too. What is going on?

There’s a commotion all around Jack. Claire and I are running toward him. I need to get there first.

I need to protect him.

I need to protect Claire—I have to make this better.

Claire’s taken her coat off and gloves, running like the wind, but I get here first. There are loads of people here, and the Coach and someone are putting paddles on his chest. They’ve ripped his shirt. He is going to get so fucking cold.

What is the fucking matter with everyone?

Claire’s trying to pick him up, but he’s too heavy. I help her, and we hold him in our arms and rock him.

Claire is screaming, except it’s not a scream, more of a roar, like a wounded animal.

We’re here now, Jack. You’re safe now, Jack.

I remember your very first football match, Jack. Your eyes were worried when you looked at me, then you jutted out your chin, threw your shoulders back and gave me the thumbs up, and you ran toward Coach Brian. You were brave, Jack. I was so bloody proud of you, Jack.

I am so afraid.

People are pounding on your chest. I want them to stop. I know you’ve gone.

I know you’re not coming back.

I can feel you.

I close my eyes, and I see you.

I don’t want to open them. I don’t want you to go, Jack.

I am so afraid of you going.

*

Tom, Jack’s Brother

30 October 2018

Jack came around yesterday and asked if I would come to his match. I’m glad I can’t. When I watch him play, my whole insides get hot and wobbly. Don’t get me wrong; I love him and all that—I just hate knowing I’ll never be as good as him. I’d often nick his football boots when he still lived at home. I swear I played better when I wore them. He moved out quite a while ago, so I can’t ‘borrow’ them anymore.

Jack told me he’s going to ask Daphne Beauchamp out again after the match— even though she’s been shagging that Daniel Frost. I told him he was barking mad. Why would he want to go there again, especially after Daniel had? He clipped me around the ear—that hurt—and told me I didn’t know what I was talking about—Jack’s nearly 30. I am seventeen and a half. So what if he knows more than me? I still wouldn’t go there, and I’ve heard things about that Daniel Frost, not good things—if you know what I mean.

Anyway, forget Daphne, tonight I’m going to the school disco, and Sarah Freeman will be there. I’ve got to dance with her. She’s the fittest girl in Sixth Form and clever too. She wants to go to Oxford to study Astrophysics. I’m not sure I’m smart enough to get into Oxford, but I want to, especially if Sarah Freeman goes there.

Jack’s clever enough, but it was all about football for him. He worked hard when he was a kid and trained all the time. Mum and Dad took him to footy matches every weekend. Sometimes Mum would get so cold her nose would still be dripping two hours later—a bit gross. He got scouted for a youth team. But he didn’t make it to the professional club; by then, it was a bit late to worry about schoolwork. He did say that he might go to college to get his ‘A’ levels one day. He thinks his job is a bit shitty— he’s a delivery driver for Hermes. I’m not going to end up doing a job like that. But Jack plays football every week, and, what with that and thinking about Daphne Beauchamp. He’s okay.

I’m at the dance, and I feel a bit self-conscious, Jack says these jeans are a sure thing for pulling girls, but I don’t know. The music’s okay. Shame there are so many teachers here. I’m inching a bit closer to Sarah. She’s dancing with her friends, Cathy Stellar and Maisie Markham—we call her Measley Markham ‘cos she’s small and a little bit nothing. Sarah just looked at me, and I’ve gone all hot. I fiddle with my hair, trying to look casual, but I know my face has gone red. The music is getting louder.

The beat’s buzzing its way through everyone’s bodies. Sarah’s next to me now. Her eyes are closed as she is drinking the music. I fancy her so much it hurts.

My pocket is buzzing.

I ignore it.

My body feels alive, electric. Being close to Sarah Freeman has given me a semi, and I am very grateful my trousers are not so tight, and the room is dark enough that no one can see.

My damn phone again.

It’s Dad. What’s he doing phoning me? The game’s not finished yet.

My heart is pounding, and Dad’s crying. Something wrong with Jack. I can hear Mum moaning in the background. I can’t hear what Dad’s saying. I walk out of the disco hall into the bloody freezing outside—I wish I’d stopped to get my jacket.

The world is quiet except for the rushing blood in my ears and my throbbing chest. My knees buckle. The school railings stop me from falling.

I’m sorry I didn’t come and see you play tonight, Jack.

You can’t be dead, Jack. You’re my brother.

You know everything. And you said you would always look out for me.

I remember you telling me to work hard because hard work always pays off. I’m sorry I nicked your boots, Jack

Where are you, Jack?

I close my eyes.

You’re there.

Inside me.

I feel a thump in my guts.

That was you, Jack, wasn’t it?

I’m sitting on the steps. I’m cold, and Sarah Freeman’s sitting right next to me.

I didn’t see her arrive. Did I tell her you died? I don’t remember. Her arm is around me, but I don’t care. I just want your arms around me now. I want to feel you.

Why didn’t I come to watch you play tonight, Jack? I am so, so sorry.

*

Lizzie, Jack’s Sister

30 October 2018

Jack asked us all to go and watch him play football tonight. Huh, I’d rather stick pins in my eyes. Luckily, I have plans. It’s bloody freezing, and the thought of spending a couple of hours on the sidelines of a footy pitch is a ‘NO THANK YOU’. My friends Sally Walsh, Lucy Freeman, Tash Markham, Alice Bicknell, and I have the evening planned. The Prosecco is in the fridge, along with a bottle of Tanqueray and several cans of posh tonic. It’s the Bake-Off final, and it will be a fab night.

I can hear the pizzicato Bake-Off music winging its way through the kitchen. Noel is chatting with Sandi. I love Noel Fielding.

This is so much more fun—and warmer than watching my brother play football. The signature bake is doughnuts. Not that impressive (though, to be fair, I have never made a doughnut in my twenty-six years of life – why would I? Greggs have delicious doughnuts at six for a pound). The technical is outside in a fire pit—so ridiculous. That Paul Hollywood is an arrogant git.

A phone is ringing.

We ignore it. It rings again—and again. My guts feel weird.

Why is Dad phoning? The game hasn’t finished yet.

I feel the blood fall out of my face, through my body, and slump against the wall—dripping down into a crumpled heap. I pull my hair. I want to be sure that this is not a dream—some awful, horrific, bad joke of a dream.

I can hear Sandi and Noel laughing in the background. I wish they’d stop. Don’t they know what’s just happened?

Sally’s rushing around. My world’s stood still and my friends are on speed. They’re talking, but I can’t hear what they are saying. Tash, Lucy and Alice are on their phones, finding a taxi or something. I don’t know.

I don’t care.

Why didn’t I go and watch you play, Jack?

I remember watching you when we were little, and I wanted to be just like you. And that time, you wrapped your strong arms around me when Tommy Sittbung (you called him Tommy Shitbum—do you remember?) broke my heart. You told me I shouldn’t be with him because we could never marry and have children with a ‘shitbum’ name. And you smoothed my hair, and you wiped away my tears, and you told me that I was an amazing girl who would one day find the person who was good enough for me.

I remember believing you.

I remember crying with you when we discovered Daphne Beauchamp was sleeping with Daniel Frost.

Why didn’t I go to the match, Jack?

My eyes hurt. I close them, and there you are, resting on the inside of my eyelids.

I hold my breath.

I feel a thud in my heart like you’ve just swept through it. I love you, Jack.

Don’t go, Jack.

I’m afraid to open my eyes.

*

Daphne Beauchamp

30 October 2018

I am so excited. Jack called this morning. He wants to talk.

I fucked up. Monumentally. I never thought I would, and when I did, I never thought he’d get past it, but he has. I really think he has.

I’ve known Jack since, like, forever. We started dating when we were 15. I used to watch him play football. He was good—like, really good. He was gutted when he didn’t get into the senior team. It was a real shame, too. He could’ve been anything he wanted—except a professional footballer—and that was what he wanted more than anything else in the world. Or so I thought. I felt a bit sidelined myself— like football was more important than me—than us. Not just more important but like it was the only thing that mattered to him. That’s when Daniel Frost and I started getting close. One thing led to another, and wham bam, and he thanked this ma’am. I don’t know what got into me. Well, I do—Daniel Frost—but I don’t know why I did it. I loved Jack—I still do. I just felt so bloody lonely and neglected.

I look back now and think I was like a proper spoilt brat. I hurt him so badly. I hurt myself so badly. I hurt his family, especially my best friend, Lizzie. The only person who didn’t get hurt was Daniel Frost. He thought he was the bee’s knees. Well, that was a couple of years ago, I have tried so hard to win back Jack’s respect, and now it looks like we might even get more. He asked me to meet him in the pub after tonight’s game.

The Bake-Off final is on. I’m a big fan. Lizzie and I used to watch with the girls. I bet they’re watching it together tonight. I wish I were with them. I miss them.

I’m putting my make-up on, not too much—I don’t want to look tarty—but enough to show I’ve made an effort. It is fricking cold outside. I shall have to rethink the outfit I was planning on wearing. I dig out thick woollen tights with my almost too- short skirt and biker boots—that’ll do.

They’re making edible landscapes on the Bake-off—nom-nom. I still can’t call who’s going to win. To be honest, I don’t mind. I like them all.

My phone is ringing, but I don’t answer it. It’s too early for Jack to be calling. The game hasn’t finished yet. They’ll call back.

Now the landline. Mum’s shouting at me to pick up the phone. My heart misses a beat.

I feel a bit weird.

It’s Alice. She’s crying, saying something about Jack.

I don’t understand.

I do not understand.

Fear is seeping through my veins, but I can’t tell which direction.

Up, down, all around.

My head is spinning, my heart is racing, and the phone falls out of my hand. I can hear a wailing, I don’t know where it is coming from.

Oh my God—it’s me.

He’s dead.

They say you were running on the pitch. They say you just fell.

What do they mean—just?

I’ll never be able to make it right with us, Jack.

You will never know how sorry I am, Jack.

Oh my God! I will never feel your arms around me again. Jack, I love you, don’t be dead.

Please, please, please don’t be dead. DO NOT BE DEAD!

I close my eyes, and there you are.

I can feel your nose touch mine, tip to tip, like an Eskimo kiss. I feel your breath on my cheek, on my neck. My heart jolts.

I feel you pass through me—taking a piece of me with you.

I don’t yet know if you left a piece of you with me.

Have you, Jack? Have you?

Can you forgive me, Jack—can you?

How can I forgive myself?

I don’t want to open my eyes.

Don’t let this be real.

I don’t want to live without you.

Tarina Marsac is a British writer who lives in South-East London. She is studying for an MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck, University of London.

She is a wife, mother, daughter, sister and friend. Her biggest challenge has been to find space in her life and allow herself to take it. After years of writing from the dining table, the coffee table, a blanket-covered lap and her bed, she is now writing in a room that is sometimes her own.

The image, Sudanese kids playing Football is the work of Mohammed Abdelmoneim Hashim Mohammed and is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The Monster of Invidia, by M L Hufkie

“I’m very sorry sir. We did all we could.”