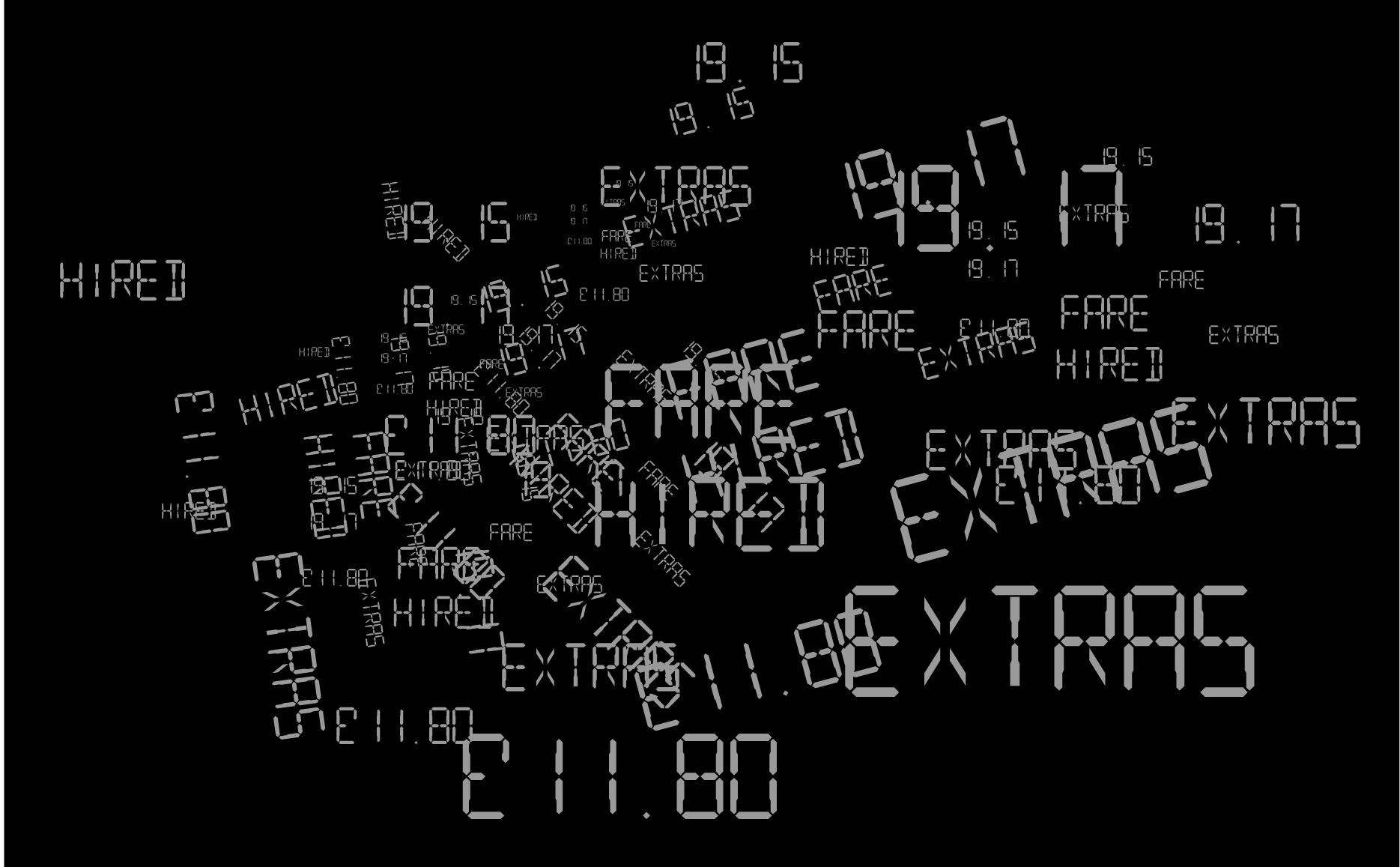

The dashboard clock ticks through to a new reading – 19:15. Still not here. He rings again, but there’s no answer. Slanted rain dances with Michael’s windscreen wipers, pushing new waves of droplets to the corners of the glass. The standing fare rises to £11.80 and he tenses his jaw.

If this guy doesn’t show up soon, Michael thinks, I’ll have wasted at least two good trips. It won’t go down well at the house.

“Come out with us, watch it from the college green with everybody else,” Fiona had urged earlier. The baby blinked at him from her arms, eyes wide-open and expectant. Not old enough to process her own disappointment, but old enough to feel Michael’s repeated absences and begin resigning him to secondary character status in her tiny life. The thought of his creeping irrelevance causes another bleep of alarm.

“No,” he’d answered anyway, ticking off the reasoning on his fingers:

1. He hadn’t yet paid off the cost of the car.

2. The cat’s flea treatment was costing too much.

3. It would feel strange to be there with just her friends and none of his own.

She’d just looked at him, disappointed.

He doesn’t remember ever feeling this deficient at their old place in the city. They’d been in the middle of things there, with friends posted every couple of miles to encourage the voicing and repackaging of any concerns.

19:17. The town hall chimes the quarter-hour. It’s always two minutes behind, which suits Eastbourne – a place where you can be minutes out of sync with the whole country, indefinitely, without repercussions. Next to Michael’s cab in the car park, there are around ten other taxis snaking in a fast-moving line from the station exit. A drip-feed of customers are emerging from the platform where a train pulled in minutes ago.

The white bodies of the cars are made alternately bloated and un-bloated by raindrop distortions on the windscreen. They chain like a river towards the sea of the open road, passengers ensconced, breaking away at the traffic lights to take separate routes.

Fuck it, Michael thinks, I’m joining the line.

He’s not meant to participate in the club of the taxi rank – his car is booked rides only – but it’s been almost twenty minutes and he can’t wait here all night. It’s the ninth of October, and the lights have been all over the news for the last 24 hours. Visible for the first time in the UK. Keep your eyes peeled at 21:00. He suspects that at least half of those queuing want a ride to the cliffs, and he estimates that he can make it there and back three times before the lights show themselves. That’s three x thirty-minute round trips, which might mean he can take the baby’s birthday off next week.

Michael starts the engine and intercepts at the side of the line. The queuing car behind him beeps in protest, and he can see in the wing-mirror that the driver is his neighbour from three doors down. Shit. Is he recognisable? Michael likes this one – can’t quite remember his name. So helpful with those boxes on the day of the move.

Breath suddenly rapid, Michael taps at his chest. The sting of his neighbour’s anger is intolerable today and he wants the feeling gone. He closes his eyes, looks for the switch to his heart, turns it off, and sends it gently through the passenger door.

This is a new skill of Michael’s. It first emerged last year, on the evening when Fiona went into labour while he was out on a job in Bexhill. He feels relieved to have the strategy in his back pocket, for these moments of overwhelm that are getting more common and less predictable. There is an order to how it happens:

The first phase is always a blitz. On the night of the birth, it sounded something like: Baby coming nearly a FATHER wife in pain alone not close no friends neighbours what was the way to the hospital? The thought crush occurs when there are too many immediate and consequential decisions to be made with no-one and nowhere to defer to.

Then, right at the point where the swarming, unresolved weight of this starts to constrict his chest and vision. Michael scrunches his eyes shut, looks into his centre, and removes his heart from between his ribs. Sometimes it floats above the vehicle with pulsing redness, tracking Michael’s journey like a drone. Other times it rolls off to the side of the road into the gutter while his body drives the car away.

With all the emotional urgency removed and the thoughts hazy, he can keep driving without pulling over, ticking his tasks off one-by-one. Remain useful by not feeling everything too closely. He hasn’t yet told Fiona about it. He’s worried that she’ll send him to the doctor.

Michael puffs spools of warm air into his hands, making a little prison of warmth to guard his extremities against the October night. He restarts his standing fare and turns off his phone. He’s soon at the front of the line. A man is waiting there.

Michael’s relieved to see a male frame. Since that article came out about the attacks from the taxi driver in Polegate he’s felt observed, untrusted, like he’s guilty by gender association.

Michael squints at the blurred outline of his new passenger as he moves towards the window. Short but top-heavy, with a torso carrying enough weight to give the impression of leaning slightly forwards even in neutral standing. A black-clad arm reaches out to grasp the passenger door handle.

As the back door cracks open, the sound from outside crashes around the vehicle. Other people’s tyres rolling through gravelly wet, a car horn sounding at the traffic lights, the broken-up noises of a couple conversing as they cross the road behind Michael’s car. Then another sound, in the foreground, from his passenger:

“Evening.”

Michael hears the thump of body-lowering-into-seat at the same time as the door shuts again, sealing the two men into their respective roles and positions – a new, temporary relationship.

“Where to?”

The man rubs his eyes with harshness, and Michael’s own retinas feel itchier from just observing him. His face is creased like weeks’ old linen in a way that makes him difficult to age. Forty? Fifty?

The new passenger coughs twice before confirming, “Up the Downs please, thanks.” There’s a warmth in his tone, but a sluggishness too, a blending together of words without distinction. Michael can’t tell whether he’s been drinking or if this is what his voice always delivers.

Up the Downs. When they’d moved to Eastbourne last year, Michael had quickly learned to adopt this way of describing the cliffs around Sussex. Driving up the Downs, he soon discovered, just meant up to the Downland. He likes the phrase. It collapses in on itself with a comforting anti-drama.

“Trying your luck with the lights as well tonight?” Michael ventures, without much expectation. He is calculating the boundaries of the interaction, wondering whether the clam shell of conversation will open or remain sealed after a couple of pokes.

Pulling out into the road, Michael’s heart pulses at him from his wing mirror view, reminding him to relax.

The passenger rubs his eyes again, yawns, before responding.

I’m tired too, Michael wants to say – exhausted.

“Yup,” he assents eventually. “I’ve got some friends already up there.”

Inefficient, thinks Michael, that they didn’t just meet down here. It was going to be a lot harder to find each other in the dark.

The two men are driving up and out of the town, soon to abandon their current view of houses for one of grassland and a flat, dark aspect of the Channel stretching out to France. As they motor forward into the night, Michael is travelling backwards at the same time, to his earlier argument with Fiona.

“We’ve never even been inside that new car,” she’d accused. “You’re in it all day long and you’ve never even taken us on a trip.”

She talked about the car like it represented secrecy or selfishness or something else about him that she didn’t like.

I didn’t buy it for you, he’d wanted to say, I bought it for work. Which means it’s for us. But it’s dishonest. In fact, the image he has of the whole family contained in the vehicle – baby, Fiona and him – isn’t incentivising. The two girls have a familiarity, an ease of co-existing. All that time in the house, all those journeys between home and the park and the supermarket, adding up to a shared week, a shared life. With them both in his car, he’djust be on the outside of their series of references – favourite characters from daytime television programmes, the specific grumbles, or repeated motions that, to Fiona, so seamlessly indicate his daughter’s fluctuating physical needs.

“That’s my old school.”

Michael looks to his right and sees that they are about halfway across the stretch of a broad, blunt building. The place has an impenetrable look, like some kind of facility.

“Looks intense,” It’s the best thing he can think to say. The rearview mirror finds his passenger looking down, the folds of his face even more pronounced. It’s hard to imagine him as a child in that building. The thought of him running across a playground or a hall doesn’t come easily.

Try again, Michael thinks, you can use this opening.

“I had a horrible time in school personally,” offers Michael, “Deputy head really had it in for me.”

There is nothing but the vibration of wheels on tarmac in response. Outside in the open, Michael’s heart coasts along on jets of air created by the car’s speed, being buffeted away to a continually safe distance.

“My daughter’s just started in reception,” he tries again. “You got any kids?”

For a while there’s more silence. Between the angle and the light of the rearview mirror, Michael can’t tell whether the man has his eyes closed.

“Yes, one,” he replies. “She lives with her mum.”

“Ah, complicated.”

This is something close to what he’s meant to say, but Michael would rather ask the stranger about his other suspicions. Namely, his niggle that living alone would actually feel expansive. How does it feel, he might ask, to go home and open the front door and not be greeted by years’ worth of resentments? It can’t be possible for him to be actively failing Fiona every day, but his presence seems to remind them both of a more structural disappointment. When had he stopped watching for this? How had their joint choices built up all this anger?

If Michael were to ask his guest any of this, there’d be a chance that the guy would relate. But, almost quickly as it’s arrived, the men are missing their turning for connection. Thinking about it, the near-touching, Michael’s breath begins to feel faster and less his own. His fingers tighten around the wheel and, to his left, sees that his heart is also on the move. He watches it outside, drawing closer to the car door.

The two men in the car are approaching the steep incline out of the town, eyes hungry for the same sight. They are getting closer to the edge of the country’s tile. Cresting the hill, flanked on either side of the vehicle by skeletal trees, they both crave the sea. There it is. Wide, black water with white tips. The ocean is so far below them now that any sense of rolling motion is lost. In the dark, barely illuminated, it looks more like a black abyss than something muscular and shifting. Whenever he comes up here in the daylight, Michael’s decision to move his young family to the town feels validated by the space that the ocean opens up in his brain. Looking out at the wide, wide dark, he rolls down a crack in the window. Salt-stiff breeze propels his heart back through the window and into his chest. He exhales.

The two men pass a sign, lit up by Michael’s headlights, that welcomes them to Beachy Head. A white glint of the chaplaincy building rushes past. It won’t be long to the nearest car park.

“If you could just drop me somewhere here,” coughs the passenger, “I’ll be fine on my own from here.”

Michael is thinking about Fiona again as he slows the vehicle. The monolith of blue-black makes him crave warm touch. They should come up here at the weekend, all three of them. That’d been the idea when they’d moved. Neither had wanted to accept that London rents were pushing them out, but the promise of nature in Sussex had done lots of heavy lifting in their conciliatory discussions about the future. This stretch of earth and water had represented positive things: the potential for refreshment, the time and opportunity for having serious conversations side-by-side whilst crunching across frost-tipped grass in the winter months. “Just ten minutes from all that space,” they’d said over and over again as they packed up the flat. And after all that, how often had they been up here together – twice?

Michael’s tyres bump over dirt, scrabble with the uneven ground. He’s surprised by this choice of stopping point. “Are they not in one of the car parks further along, your friends?”

“No, no. They’ll have found their own spot. They’ll be over there somewhere with a head torch. I’ll catch them.”

The left side of Michael’s car faces out to the cape. Even in the almost dark the headland is visibly flat all the way to the cliffs. There are no yellow streaks from a torch bulb. No recognisable imprints of bodies in the gloom.

The passenger undoes his seatbelt, pulls out a wallet, and pays with a £10 note. The whole journey has taken fifteen minutes.

“Thanks.”

“Thanks.”

As before, the man opens the left-hand door, popping the lid on sound from the outside. This time it’s the crackle of far-off waves that comes spilling in. In the foreground there’s an expulsion of air from the passenger as he pulls his weight off the seat and assumes control over his own movements again.

Michael angles the note so that it is readable in the moonlight – rare to get cash these days. He turns around to deliver a smile but is met with the stamp of a closing door. Looking at the now empty seat where his passenger was, the largeness of the cliffs presses in on Michael from all sides. He zooms out on himself, his car, set against the scale of the coastline. There is the fledgling sense that he has missed something important. Being up here at night, tasting your own smallness, provokes those uncertainties.

His acquaintance gets smaller as he walks towards unseen friends.

Michael rubs his chest, reaches into his pocket to turn on his phone. He hears wind more loudly than before and isn’t sure whether it’s the weather picking up or the blood in his ears. There’s a text from Fiona. It’s a nice one.

Made it to the green. Missing you.

Michael looks to his right, onto the road. Just a few minutes further along, he knows that lights from a dozen other vehicles are blinking expectantly in the car park. But they stopped here. Why? Through glass, the man can be seen rounding the dark outline of some weather-beaten brush on the headland.

Michael has been slow, but he’s nearly there now. Heat pricks in his chest as thoughts pull together, reconfiguring to acid weights in his stomach.

He throws open the car door and leaves it swinging. Running before he has thought to. Clodding and skidding on the earth. Sizing up distances only after he makes them. He is heading for the plants, the point of last sighting.

He is going to be too late. There are already so many moments to regret in the two, three minutes before this one. Examining the money, his phone. The seconds hadn’t seemed like anything to lose. Now he is dizzy with thoughts of their significance.

The mass of moonlit brush clarifies into recognisable prickles of hawthorn and gorse. Michael finds the path of least resistance around the plants and then his body is slowing him down – holding him back in anticipation of the cliff’s edge. He is only a couple of metres from freefall.

Left, right, left again.There’s nobody there. Nobody’sfucking there.

The dread is too heavy, and Michael’s heart is shot out of his chest like a stone in a sling. Just below him, he can hear curls of cold-wet breaking against the shore. He knows that he shouldn’t look down. Instead, Michael tracks the path of his heart with his eyes, towards the horizontal line where dark sky blends soundlessly into inky sea.

It is above this strip that the aurora bursts into view. Rich blue-purple, It’s arrived earlier than planned. It’s beautiful.

Author Bio

Martha Stutchbury (she/her) is an events producer living and working in London. She studies creative writing part-time at Birkbeck University and has worked as a researcher on creative non-fiction projects including Kate Summerscale’s ‘The Book of Phobias and Manias’ commissioned by the Wellcome Foundation.

Content warning: Reference to suicide