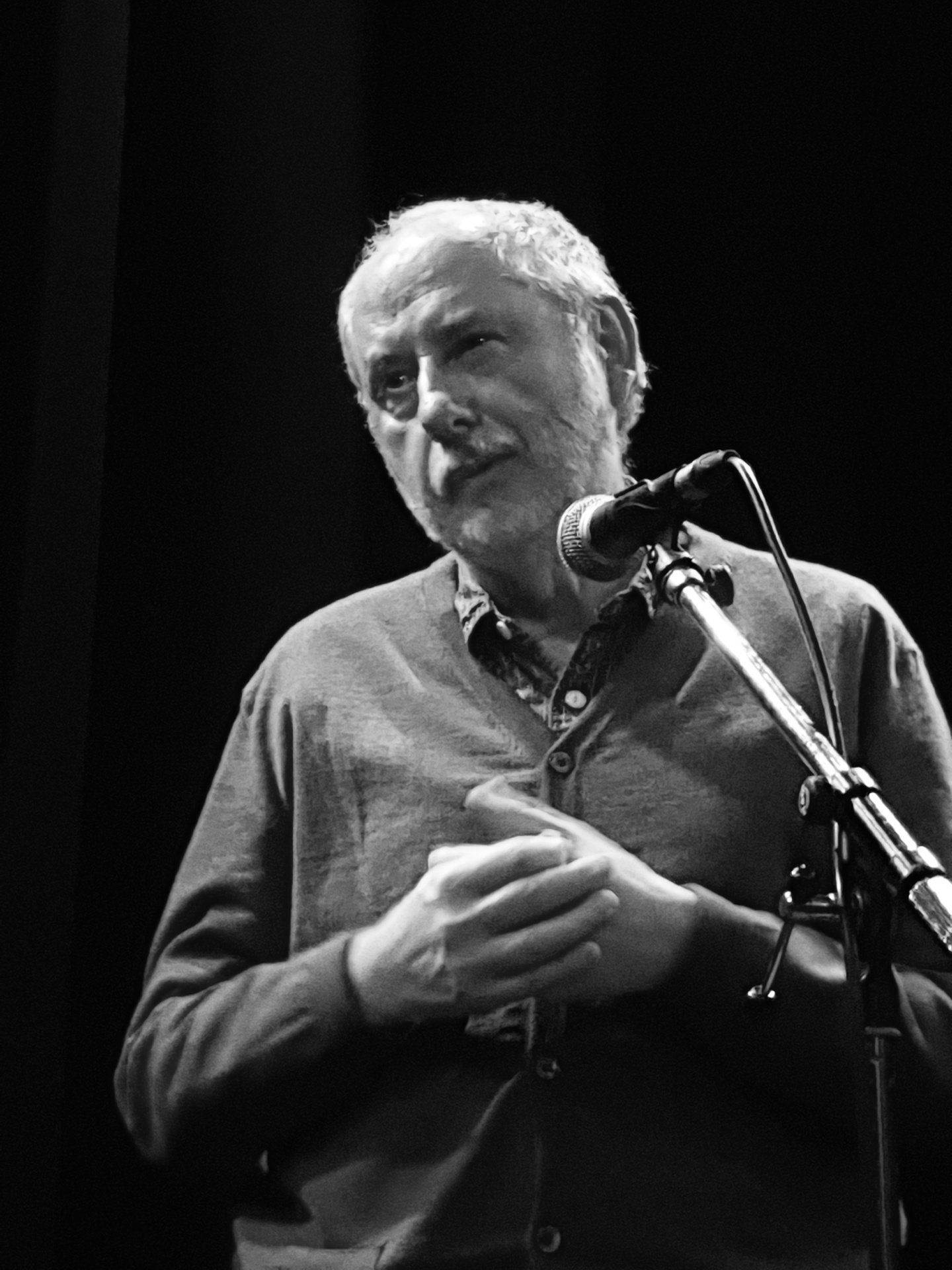

Interview: John Harvey

I first met John Harvey in the 1980’s when we appeared on the same poetry bill at Huddersfield Art Gallery. He was already a legend in the Northern and Midlands poetry circles as an author and publisher. Among other achievements, he co-founded the poetry journal, Slow Dancer, which published two pamphlets by Simon Armitage, The Walking Horses and Around Robinson, before Simon’s career took off.

John evolved into a world-renowned crime writer. His signature detective, Charlie Resnick, walked the streets of Nottingham, where Harvey was living at the time; the first Resnick book, Lonely Hearts, was described by The Times as one of the 100 most notable crime novels of the 20th century. John received the CWA Cartier Diamond Dagger for Sustained Excellence in Crime Writing, and Resnick spun off into two BBC TV series and a stage play.

John officially retired from writing in 2021, though that didn’t stop him publishing poetry in The North and London Grip, and creating Summer Notebook, a collection of short poems largely inspired by his regular walks on Hampstead Heath.

We met in his home in Tufnell Park, where we ran through his astonishing career and discussed the life of a commercial writer.

Craig Smith: How did you become a writer?

John Harvey: Writing, in my case, had almost nothing to do with wanting to be a writer and practically nothing to do with having something to write about. After twelve years at the chalk face, I was looking for an alternative to teaching.

A friend, Laurence James, had been working as an editor, and later as an author, for the New English Library, who published pulp fiction. Lawrence was writing a series about Hells Angels but was busy on another project, so said, ‘Why don’t you have a go?’ After I’d submitted, with Laurence’s help, an outline and a sample chapter, New English Library contracted me to write 50,000 words for £200 plus royalties. Then, when I delivered the manuscript, they said ‘Give us another one,’ and offered £250. So I resigned as a teacher, thinking I could always go back if it didn’t work out.

I co-wrote several series of Westerns with Laurence and Angus Wells. We talked about the basic storyline and main characters, then we wrote alternate books. Over a period of five or six years, I wrote 12 or 13 books a year. You didn’t get paid a whole lot, so you needed to write a good number of books to get by.

I found, to my surprise, that if you sat at 10 in the morning and stayed until 3:30, you had a lot of words. In four weeks, I had 50,000 words, which was a 128-page paperback. As a beginning writer, which I still was, it was like being paid to practice, to learn how to tell a story, to keep the readers’ interest, to balance action against dialogue.

Eventually, I got a little bit restless, and the market for Westerns dried up.

It was remarkable that your first writing was paid.

If I hadn’t been paid for it, I wouldn’t have done it. I’ve always seen myself as a commercial writer. I write to make a living, except for poetry, of course.

CS: What did you know about cowboys or bikers?

JH: Cowboys were easy because the readers wanted a regurgitation of the myth you get in John Ford or John Wayne movies, rather than any serious attempt to write about what it would actually have been like. Biker books were Westerns on Harley Davidson.

CS: What did you do next?

JH: I went from pulp fiction into writing for television and radio. The first major thing I did was a television adaptation of Arnold Bennett’s Anna of the Five Towns for the BBC, which led, a few years later, to Hard Cases, a six-part series for Central Television about a group of probation officers and their clients. This was filmed on location in Nottingham, which gave me the idea of writing a police procedural in the same setting – hence Resnick.

CS: What did you know about police work back then?

JH: I wrote to the public relations department of Nottinghamshire police and said ‘I’m planning to write a novel about a Nottingham-based detective, could I talk to someone about it?’ I didn’t want to drive the streets in a police car at 1am, I wanted to know what the routines were. How many people were on duty, who came in in the morning, who made the tea?

Later, I worked with a serving police inspector in the Nottingham force, right through until Darkness, Darkness. He’d been involved in the policing of the miners’ strike, and had very ambivalent feelings about the way it was policed. Later still, I got to know a senior officer in the Met. At his suggestion, we did some joint sessions in London libraries, where he talked about crime and I talked about my books. After that, I would run stuff past him, as well as my Midlands contact. I’ve always had somebody that I could run my stuff by to make sure I got the procedures and the acronyms right.

CS: Were there writers you tried to emulate?

JH: I was influenced by a Scottish writer, William McIlvanney, who wrote three novels about a Glasgow-based policeman called Laidlaw, as well as the Martin Beck novels by the Swedish writers, Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö.

There was a move towards what I hoped was a greater authenticity. It was social realism plus crime. Crime gives you the story, but the background is social realism. I was working toward a picture of Nottingham that was as accurate as possible, where the characters were as accurate as possible, and the storyline opened up things about living in that place, while providing a narrative to follow.

Instead of writing 12 books a year, I wrote one book, so I could expand those parts which I couldn’t linger over in the shorter stuff. I could spend more time on character, on describing place. I could have some kind of political attitude, if it fitted with the story. I could be more careful about language. I could do a lot more rewriting. There was no rewriting on the early stuff because there wasn’t time.

I had plenty of time to write the first Resnick novel, Lonely Hearts. I had time to revise it. I had a proper editor who went through it and told me ways in which it could be improved. I had an agent. I was operating on a wholly different level.

CS: Did you know it was going to be a series at the beginning?

I didn’t. But I had been working in series with the pulp stuff so it was no great surprise when the publisher suggested it.

My agent sent out the first 50 pages of Lonely Hearts, plus an outline, to the major mainstream publishers. They all turned it down except for Tony Lacy at Penguin, who asked to read more. It’s always amused me that, when he read the full manuscript, his comment was to the effect, ‘This is better than I’d anticipated!’ It was Tony who first asked if I saw it as part of a series. And, I said, ‘Oh, yes.’ Obviously, the idea appealed to me.

CS: When you wrote the second Resnick novel, what could you presume about its readership? Did you assume they carried over from the first novel, or was it was an entirely different audience?

JH: I’m not sure if, at that stage, I was too clear about it. It wasn’t until the third book that I realised that what readers responded to was Resnick’s character. Initially, I thought it might be an ensemble piece. But it became clear from readers’ and publishers’ responses that what drew them to the book was Resnick, rather than the subsidiary characters.

I gave Charlie one or two characteristics of my own. He loves listening to jazz so I could write about jazz. I gave him hobbies that suggested a rich inner life to stand against the grim work he does. I didn’t want him to be a grim man, living on his own, dealing with awful things. I thought, ‘Who’s gonna care? I’m not gonna care.’ There needed to be aspects of him that people could respond to in a positive way.

I gave him a Polish upbringing. I wanted him to be of the city of Nottingham but somehow not of it. I assumed his parents moved to Nottingham as refugees during the Second World War, and that he’d been brought up there but saw himself as an outsider. I wanted this insider/outsider thing. I tried to signal that by having him buy Polish gherkins from the deli stall in the market and making strange and ornate sandwiches.

It became evident that readers took those elements of the books to heart. That’s why they’re buying the books, and it’s why those books sell in series.

CS: Were you aware of the passage of time in Resnick’s life as the series went on?

JH: I regret not keeping 6”x4” cards with dates and names. It would’ve been a great help, instead of going back to the earlier books and trying to work out, ‘What was so and so’s name and when did such and such happen?’

I was constantly fudging it. ‘It was Resnick’s birthday, but he wouldn’t say which one.’ He was always older than the people he worked with, but not so old that he should retire. I think by the time of Darkness, Darkness, he was probably in his early 60’s. I should’ve been clear about that stuff but, having fudged it from the beginning, I carried on fudging.

CS: How did Resnick end up on TV?

JH: An independent company got a contract from the BBC to film the first two books, which we did on location in Nottingham. Each one appeared in three parts. It was Resnick: Lonely Hearts; Resnick: Rough Treatment.

CS: How did it feel to break a year’s work into three parts?

JH: I loved it. I’ve always loved adapting other peoples’ books for radio and television drama. Back at grammar school, we did something called parsing, which means you read an article say, in the Times, then created a 50-word summary in readable prose that picked out the salient points. That stood me in good stead when it came to adapting work from one format to another.

CS: And how did Resnick become a play?

JH: Giles Croft commissioned me to dramatise one of the Resnick novels for the stage and I chose Darkness, Darkness, which I thought would be the most interesting because of the way it dealt with the miners’ strike. Giles suggested Jack McNamara as a potential director. Jack worked with me from an early stage, workshopping the script with mostly local actors before the main casting. It was really hard listening to my scenes for the first time, realising very quickly which bits did not working. Jack was basically saying to them ‘What’s wrong with this scene, what are the weaknesses?’ And I was saying ‘There aren’t any fucking weaknesses, talk about the strengths, for God’s Sake.’ We argued quite heatedly at times but, in the end, I was only too happy to accept his ideas. Well, most of them.

One thing I realised I’d been missing as a writer was being in an audience with several hundred people, most of whom responded in a positive way, not just to stuff I’d written but to stuff the director and I went through in rehearsal to figure out how to make work. If I had to choose one single favourite thing from all the writing I’ve done, working on Darkness, Darkness and seeing it evolve for the theatre would be it.

CS: How did Slow Dancer come about?

JH: I met an American called Alan Brooks on an Arvon Foundation poetry course. We had similar ideas about poetry. He was living in North London, quite close to me. Our work was getting turned down elsewhere or was being published in badly mimeographed magazines, so we thought ‘Bugger this, we’ll start a magazine of our own’.

We created a nicely produced magazine containing our work and the work of other people we liked. Alan had a friend, David Kresh, who ran the small press poetry section of the Library of Congress, who suggested American writers to publish in our little English magazine that few people in the States would have heard of. And, although I applied for grants, my writing subsidised the poetry.

CS: So this was while you were writing pulp fiction?

JH: It began when I was writing pulp fiction, then continued into Resnick.

CS: When you write fiction, do you have a pen and paper at your side, ready for the next poem?

JH: I wouldn’t say one thing fed off the other. Poems occurred to me when I wasn’t thinking about writing, late at night or listening to music or out walking.

CS: Did your prose benefit from your poetry?

JH: I thought more about my choice of words. What poetry teaches you is to be selective and precise. It encouraged me to use only one adjective instead of three.

CS: How did you spot Simon Armitage so early in his career?

JH: What impressed me, as much as the actual writing, was Simon’s commitment and self-assurance. There I was, thinking I was doing him a favour by asking if we could publish one of his poems in Slow Dancer, and he’d already had it accepted by the Times Literary Supplement.

CS: What does success look like for you?

JH: Early on, it was ‘Are they going to commission three books in the series? Can we get another series going?’ I was working on four or five Western series at a time for different publishers, because working on one Western series with another writer didn’t pay enough to live on. So success, initially, was placing books with a publisher, getting them written, seeing the artwork: the same thing that goes on with any book, the excitement of seeing the finished book. Those books never got reviewed so it was a matter of self-indulgent enjoyment. The fact that publishers wanted them was how we made our living.

When I started writing for radio and television, I got more concerned about what people said and what people thought, about what the reviews said.

With television and radio, the enjoyment was watching or listening to the finished thing. Being in the studio when a radio play was being recorded was especially enjoyable, because it’s you, the producer, about three technicians and the actors. They want you there because inevitably time becomes a crucial issue. The producer’s assistant will be clocking the time and working out how much you’ve got to lose, so you’re rewriting all the way through.

CRAIG SMITH IS A POET AND NOVELIST FROM HUDDERSFIELD. HIS WRITING HAS APPEARED IN THE NORTH, BLIZZARD, AND THE INTERPRETERS’ HOUSE, AMONG OTHERS. CRAIG’S THREE PUBLICATIONS SO FAR ARE: THE POETRY COLLECTIONS, L.O.V.E. LOVE (SMITH/DOORSTOP) AND A QUICK WORD WITH A ROCK AND ROLL LATE STARTER, (RUE BELLA); AND THE NOVEL, SUPER-8 (BOYD JOHNSON). HE IS CURRENTLY WORKING TOWARD AN MA IN CREATIVE WRITING AT BIRKBECK UNIVERSITY. HE TWEETS AT @CLATTERMONGER

IMAGE: Molly Ernestine