Review: Instructions for the Working Day by Joanna Campbell

Kerry Mead reviews Instructions for the Working Day by Joan Campbell

‘You go too far, my friend. You are near dangerous ground.’

Good literary fiction often delves deep into the human psyche and the myriad of ways the intricacies of human interaction can take form. Some literary fiction, for example, Anne Michael’s Fugitive Pieces, Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance, or Sebastian Faulk’s Birdsong, act as proof that literary fiction set against a historical backdrop can also teach the reader something about our shared histories. These novels make use of the human to flesh out historical events and make them more relatable; also using creative narrative to conjure up the atmosphere of that time, connecting us to the felt, emotional landscape of a particular place, something a history book can never do.

Joanna Campbell’s second novel Instructions for the Working Day, published by Fairlight Books and available in hardback from August 31st, is one of these books. Set in present-day East Germany, Instructions for the Working Day not only weaves an uncomfortable, gripping story of foreboding but also leads the reader to a better understanding of the deeply felt ramifications of the post-war era of the German Democratic Republic for a whole country and its residents, the echoes of which can still be felt today.

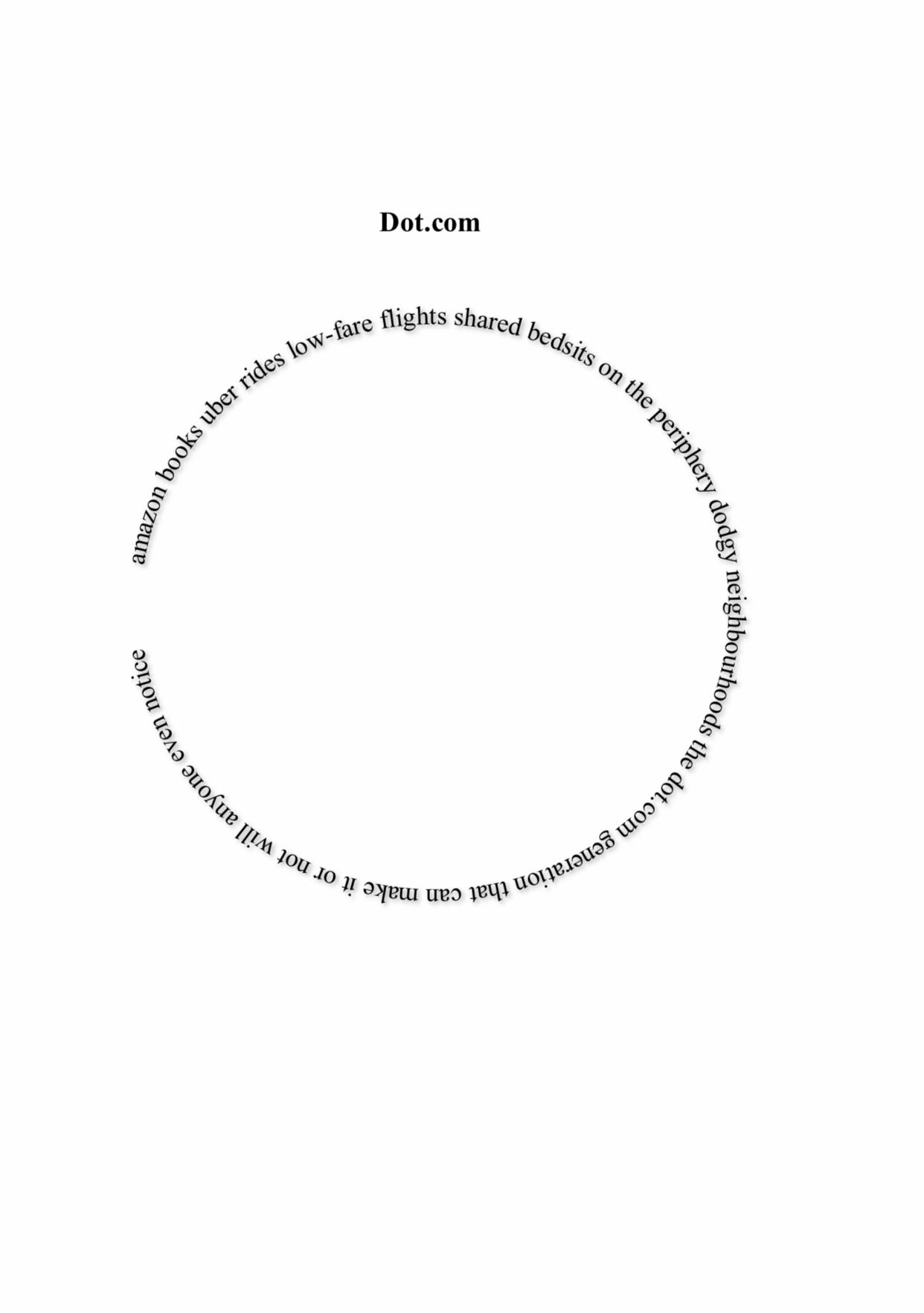

The blurb tells us that ‘Neil Fischer is travelling from the UK to a decayed, forgotten village outside of Berlin that he has unexpectedly inherited – his father’s former hometown of Marschwald’. The village has slipped into decline since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990 and Neil has visions of restoring it to its former glory. As Neil makes his way to East Germany and arrives at the village to a frosty welcome and a general sense of unease it becomes increasingly clear it may be a more difficult task than he anticipated.

Neil strikes up a friendship with Silke, who lives with her brother Thomas in the dilapidated house where Neil is a guest during his stay in Marschwald. Silke is the only resident of the village who welcomes his arrival; it is evident that, at least to start with, Silke sees Neil as a living emblem of a better life available beyond the swampy, bleak landscape that surrounds the village. As the story unfolds we revisit Neil’s childhood and more recent life back in the UK living in the shadow of his controlling and abusive father. During his time in Germany, whilst trying to make inroads into shoring up the village’s rapid decline, Neil begins finding the missing puzzle pieces that help him put together a clearer picture of what made his father the man he was. At the same time, the buried secrets of Thomas and Silke’s lives from before the fall of the Berlin wall are also coming to light. The poisoned legacy Neil’s father has passed on to his son reveals how Neil’s life and flawed, disturbed character are just as contorted by East Germany’s dark past as those around him who lived directly through the Stasi regime, and how difficult it is for any of them to be free of its lingering shadow.

Instructions for the Working Day illustrates Campbell’s strong knowledge of the craft of prose writing. She creates a distinct sense of foreboding throughout with her use of clean, stark language and sentence structure, a certain flatness which hints at the banality of evil, as well as deftly conjuring up an atmosphere of deep rot and decay through her descriptions of the physical landscape of Marschwald and its surroundings. Part of the narrative’s beauty is how the very fabric of place and experience described in the novel manages to demonstrate how living under Stasi rule must have felt for most East Germans between 1950 and 1990. The very ground of the landscape and the story’s atmosphere shift and stifle, leaving the reader with a sense of unsteadiness underfoot, of not knowing whether to trust anything that appears solid. At the same time there is a sense of something being held back or concealed from full view that both unsettles the reader and propels you forward to want to uncover the truth.

This is a story of trust, mistrust, shifting loyalties, and the traps we fall into when we are tempted into a false sense of security. Questions are raised about who and what we should and should not rely on, trusting the wrong people, putting blind faith in strangers, and how those who we trust the most are best positioned to cause us the most damage. Narrative truth becomes harder to pick apart from illusion as the book progresses; a building sense of the boundaries blurring between what is hallucinatory and what is a ‘real’ occurrence in the story is hinted at right from the opening chapters. Neil’s increasingly tenuous grip on reality bleeds through the pages with rapid intensity as the book progresses; there is a tangible sense of being increasingly unsure of your innate ability to work out what is real and what isn’t by the time the novel reaches its conclusion.

This is a novel that does not shy away from presenting the stark reality of the horrors we human beings are capable of inflicting upon each other, and cuts open the dark, insidious underbelly of the human psyche we often avoid acknowledging, presenting it to us in such a way that we are forced to examine it closely. Campbell fully understands that it is in these hidden corners of the human character that the answer to questions about how the Stasi regime and other cruel societal constructs are created and upheld are found. But, without falling into the trap of providing a happy ending, Campbell also provides a glimmer of hope in the closing pages of Instructions for the Working Day. It is hard fought for, but there is a redemptive arc present in one of the character’s storylines which illustrates that we also have the innate ability not to be forever scarred by the cruelties enacted upon us in the past and succumb to the fate it would seem life has presented us with. Sometimes, if we are astute and strong enough, we can claw out of the quicksand and make a grab for an opportunity to change our own endings.

Instructions for the Working Day by Joanna Campbell is currently available in hardback from Fairlight Books.