A Marathon of Russian Roulette, a documentary play by Kateryna Penkova

In the morning the planes started flying.

How can that be?

Well, I thought, they’ll fly around a bit and that’ll be it. We’ve got school in two hours, work.

The first strike came at half past four in the morning, nearby.

We legged it to the school to hide.

I looked at the building’s panels – they’d crumble quick as a flash and we’d be crushed.

We went back home.

Nightmarish shelling. A sea of soldiers setting up equipment. They were already asking some people to leave their homes.

But for some reason I was certain that they’d shell for a bit then stop. This was Mariupol, after all. We’d seen it all back in 2014.

I left Donetsk when it started there. Escaped with my two children. My ex-husband’s on the other side.

I was just very afraid. He’s so domineering. He’s so high up in Donetsk that he could have killed me and got off scot-free. All the guns were pointing at me. He used to threaten me and kick me out and keep me in the cellar.

So, there we sat. Waiting for it all to end. Planes were flying. So low they were right above your head. The building was shaking. Terrifying. We had no more electricity, water or gas. Bitterly cold. We all slept in the corridor in puffer jackets.

My friend rang – ‘Come over and charge your phones, we have electricity’.

So we went.

Everything was screeching, booming, flashing, exploding.

We shouted to each other but couldn’t hear a thing.

My friend’s street was much quieter. Like a whole different world.

There was water and electricity. We charged everything: power banks, phones.

She put us up – ‘Stay the night’. We put the kids in a room, a closet with no windows.

A small one, the walls are thick there.

I breathed a sigh of relief. The little one fell asleep at last.

We calmed down almost immediately – water, light, warmth – we could relax.

Everyone had bedded down and I was lying there on my phone.

They say that if you hear a whistle the shell isn’t coming for you, it’ll pass by.

But there was silence.

I looked up and like in The Matrix…

A shell burst straight into the flat… through the window.

Slowly, for me it happened slowly.

Shards of glass, chunks of plaster, so much dust, so much everything.

It seemed to me that the building swelled up then deflated again.

The shell flew in and I thought that I could stop it, grab it, catch it with my bare hands. Because it was flying towards… Towards the room where my child was.

I jumped up and ran.

I looked, she was whimpering, concrete on her head, you couldn’t see shit, there was a cloud of dust. I had only one thought – please let her head be intact. At home she used to sleep with her pillow over her ear. And that saved her. I looked – phew, seems it’s in one piece. Then my elder daughter said, ‘Mum, her legs’.

What do I remember about bleeding?

There are two types: venous and arterial.

Venous is a stream of dark blood.

Arterial is a fountain and bright red.

For venous bleeding you need to use a compression bandage and raise the limb.

For arterial you need a tourniquet a bit higher up, and then what? Then you pray.

Because while you’re figuring out how to apply the damn tourniquet, the fountain will… run dry.

I bandaged her legs as best I could.

No signal. Shock. What to do?

We got dressed quickly, got ready as best we could.

We ran to another building. Somehow found internet connection. I messaged all the group chats.

I messaged Typical Mariupol, gave them the address – a child is wounded.

The police came, giving each other the jitters. They nearly shot us because it was dark, who knows who could have been there.

‘A child is wounded,’ I shouted.

Then they came closer, looked at us – ‘We’ll take her.’

‘She’s eight years old. Where will you take her? My elder daughter’s still in the basement.’

‘Either stay with the elder one or come with the younger one.’

I went with the little one, of course. And my eldest stayed put. We dashed through horrific shelling. We got to one hospital – they didn’t open the door. Either no-one was there or they didn’t hear us. One of the policemen shouted into a loudspeaker. The door stayed shut. We went to the emergency hospital. They took her. What’s going on? I just don’t understand. Soldiers were hugging me. They surrounded me:

‘Oh no, it’s a child.’

‘Stay strong, Mama.’

I don’t understand, I don’t understand anything.

Out came a doctor. I was shaking, my hands trembling. It was agony to look at him. I was so afraid of his face…

And he said, ‘People don’t survive wounds like that. At least they don’t walk away with both legs intact. We removed this. It was a millimetre away from an artery. A little curved cone. It’s not shrapnel. It’s the tip of an artillery shell. Maybe a ricochet. I don’t know. It went through one leg and got lodged in the other. Here in the soft tissue. I don’t know how that’s possible. We just got very lucky.’

After the operation they took us to Hospital No. 3, to the trauma unit. And we slept soundly until morning.

That was 8 March. When it all started.

Sound of an aerial bomb falling.

The shockwave was just… It knocked me off my feet, even though we were quite a way from where it landed. But the shockwave got us.

The drywall shook, the windows were blown out. I grabbed the little one, twisting round so she wouldn’t get hit. She had stitches, tubes, all of that.

I dropped to the ground, turned over, shielded her. A man was running, shouting, ‘My child’s on the first floor!’

Soldiers, doctors… everyone was shouting.

‘Everybody to the bunker!’

It wasn’t far. You could see it from the window. But I went to pick her up and had no strength to lift her. And I needed to take the bags and her bed-pan. Because how else could we stay in that bunker? It was cold and dark. Such fear, such adrenaline. A soldier dashed up, grabbed her and ran. I snatched the bags and followed.

I looked and saw wounded pregnant women running. A sea of crying children.

We ended up there. The hospital was destroyed. But they set up an emergency unit. And people were arriving amid the shelling.

They simply threw some people out on the street, because they knew that they would die. There was absolutely no way to help. If there was nothing left. Barely a head left. No arms or legs. Nothing left at all. Just a stump lying there. I didn’t think people could walk or live with those kinds of wounds. They were crying, begging, ‘Please don’t abandon us.’ They crawled out of that hospital. It was just a horror film.

It turned out that the only doctors with us were two trauma surgeons. And that was it.

There was one 15 year-old boy called Sashka.

The doctor shouted to me,

‘Hold the torch! Shine it into the wound!’

I couldn’t watch them cutting into a person… a child.

I knew that I had to help. But I couldn’t. The smell, the blood, the flesh.

They gave the torch to a guy and – bam – he fainted.

I watched and thought, Jesus, he’s only 15. Same as my eldest.

He was looking at me, going,

‘Will I survive? Will I survive?’

I grabbed the torch, my hands were shaking but I held it and said,

‘Of course. Of course you’ll survive. Don’t go anywhere.’

We couldn’t even count the holes in him. They were poking around for four hours.

We turned him over, he was a mess. You could have stuck two fingers into his neck. My whole hand would have fitted into his leg. And he was still going,

‘Will I survive? Will I survive?’

He so wanted to live. They got everything out, bandaged him up.

There was one woman with two children, Anya. ‘I don’t know where my third child is, a newborn,’ she said. ‘He got left behind somewhere in the hospital.’

The doctors conferred privately. There’s no-one in the hospital. The hospital’s gone. All the children died. Should we tell her, not tell her?

‘We’re searching,’ they said. They were covered in burns. She and the children. ‘We’re searching.’ She kept hoping.

I believe in God. There were no non-believers left in the bunker. I don’t know how to pray, so I just talked,

‘Lord, you saved my life. I’m in a bunker. Why did my elder daughter… where is she? Huh?! Why did this happen? How can I understand it?’

God said nothing. He was probably offended that I’d never come to him before.

We were on the Right Bank and she was on the Left Bank. Separated by Azovstal. Not a chance you could get there.

We started treating people, somehow I pulled myself together.

I got used to that smell. I began to recognise what was clean, what was infected, what needed to be done.

If I didn’t know, I’d shout, ‘What should I do?’ The doctors would reply.

We divided up the wounded – you take those ones, I’ll take these. And we worked like that.

There was a different sensation in the bunker. It would sink into the ground after a blast. The sensation that it was right there, striking the bunker head-on. I just cannot believe that I’m still alive after blasts like that. Before the war it was used for storage. And we were very lucky, because we found surgical lights there. We found operating tables, surgical film. We marked out an area, made it as sterile as possible.

One night someone came and banged on the iron door.

People were screaming involuntarily in pain. Children. You can’t explain to a child that they need to be quiet because someone’s at the door.

They tried to break it down.

Sound of machine gun fire.

It was terrifying.

It was as if the Transformers were on the move. I couldn’t make out any other sounds. As if everything made of metal was shaking, screeching, clanking, trying to get you, hunt you down.

We consulted with each other. Decided that we needed to make our presence known.

We drew red crosses on pieces of film with felt-tip pens.

But how to hang them up? We’d have to go out there. And you realise that out there are bullets and grenades and grenade launchers, equipment.

It was a genuine feat going out there. Because we had to fasten the signs. And that takes time. We rushed out in short bursts and attached them.

Then it seemed to subside. We decided to see if it would last or not.

We crawled out of the bunker. And there was the blackened city. Smoke as thick as fog, only black. It was as if the bunker had been dug out of the ground. Masses of crows all around. Our crosses riddled with machine gun bullets.

That’s when it dawned on us that we were there for the long run. We had to do something.

Our food was running out. We had no drinking water. We’d been collecting snow and rainwater, but it was dirty.

We needed everything. Food, water, clothing, medicine, a generator.

So we walked through the ruined hospital. Battered down the doors. We couldn’t find any food, but there was medicine. I grabbed everything I could see.

The doctor said, ‘That’s for chemotherapy. What use is it to us?’

‘Let’s take it. Who knows? Maybe we can exchange it. Maybe someone will need it. We need everything, because people… From plaster casts to simple aspirin.’

So I crammed everything into my pockets, into my trousers, just to take as much as possible.

I wasn’t a looter. I was a medical professional.

Sound of shelling.

Jesus, it was a kids’ hospital. Not just a trauma unit – a kids’ trauma unit, a maternity hospital, a cancer ward. No military targets in sight.

What do you bastards want here?

We have no water, the kids have fuck all to eat! Kill us already, go on. Grad missiles, mortar bombs, shells, tanks… What else have you got there? Bring it all! Kill us! Go on! Just do it now. And kill us all. Anything but a slow death. From starvation or dehydration. Seeing my child dying in agony… It’s more than I can bear.

And then… we found a large barrel. A huge tank of water, about 400 litres.

Something thuds.

It was March and -12 in Mariupol. So it was 400 kilograms of pure ice inside an iron barrel.

We had to roll it towards the bunker. But how? There were mines, you know.

We stood like Repin’s Barge Haulers on the Volga. The self-appointed de-miners went ahead. The others rolled. We managed to find some humour in the midst of all this, because it was so unbelievably absurd. We cracked jokes, because otherwise we couldn’t have carried on. What else could we do?

We left the barrel to thaw – we’d keep it as sterile water.

We had to dash outside to cook food and light the campfire.

One person would dash out and throw salt in the pot. The next would run out and throw in the food. The next would run out with a spoon to stir it. A marathon of Russian roulette.

We had to cook something at least. Just something hot to eat. That’s how frozen stiff we were. We warmed each other up, took off our coats and huddled together. Because there was nothing. Nothing to warm us up.

And I searched for my elder daughter. I drove everyone up the wall. I went into every basement, every alleyway I could. I met people, described my child, showed them pictures. I couldn’t find her anywhere. I hoped against hope. She knew we were at the hospital. I hoped she would somehow start moving towards us. Because I couldn’t. The little one couldn’t walk.

We went to a bombed-out military base. We found duvets, there was food there, thank God. We brought back bread for the kids – they sniffed it. We didn’t give them the whole thing. We cut it into morsels. Gave them the morsels. The little one only ate the soft part. Then she slept. It was awful to watch. I used to cook up all kinds of things for them. They were fussy eaters at home. Soups pureed in the blender. And here, you see, my child was eating everything. Porridge, vermicelli. A spoon could stand up vertically in that vermicelli made with dirty water. We cut it off in chunks.

And she ate a little bit of that bread. Put the rest in a plastic bag in her pocket.

The kids constantly needed new dressings. Complications, haematomas. The wounds seemed to be healing but they were covered with huge lumps.

We had to operate on Sashka with no anaesthetic, awake. We looked for some but at that point there was none.

‘It’s fine, I can bear it,’ he said.

And that doctor of ours. He just loved rummaging around. Apparently he had to. ‘Stop, that’s enough,’ I said. ‘No, wait a second, he can bear it a bit longer. I’m nearly done, nearly done.’ There were scissors, he did everything, dissecting, squeezing, opening him up. Then there were the dressings. The dressings had to be opened up constantly too and antibiotics slipped inside. Every day, every day.

But Sashka did so well – he stayed strong.

Then somehow I heard about a well near the Drama Theatre.

Anya and I set off. We always needed more water. Then came the shell. We fell to the ground. Tried to stand up. And she said, ‘I can’t walk. I can’t look, I’m afraid. Please can you look and see what’s there?’ I looked – and there was no heel, no knee, it had just been blown off. I don’t know what it was clinging onto – skin, flesh, muscle…

‘Don’t look,’ I said. ‘Let’s go back’. ‘No,’ she said, ‘let’s get the water, for the kids.’ And she used me as a support. We went there. Got those bloody 10 litres. Dragged them back.

Ran into the bunker. I dragged her in. We ran so fast down those stairs together. My legs turned to rubber from fear. The others even gave us surgical spirit to drink.

We had no clothing. I fashioned a pair of leggings from a jumper for my child.

There was a kids’ shop next door. But I couldn’t go in. I knew that I had to clothe my child. People were taking, taking everything. But I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I thought everything would calm down very soon and get back to normal. We’d all go home.

Oi! Why, people? What do you need that for? What even is it? A cot with a changing table, a digital baby monitor, balance bikes, scooters, mini electric cars. Where are you dragging all of that? Is this what it’s come to? What’s going on?

Things got blacker and blacker. Nothing at all was left standing in our district.

Dogs came to us for shelter. We took them in and fed them. I took in a yard dog. You could talk to her, she understood.

‘What is it, doggie? Where are your owners? Did they leave? It’s a good thing if they left. Don’t be angry at them. You’re such a clever thing. Clever girl. You understand me, don’t you? You should be happy if they’ve left. They say some buses are leaving from the cash and carry.’

Then something else started happening. People started coming. A constant stream of people. People were dying standing in line.

Some people brought others in their own cars.

‘Please take at least one person, take him.’

‘Who is he?’ I asked.

‘I don’t know. I threw him in the boot and drove him here. He has no documents, nothing.’

We went to look in one car and it was just… Are they even alive?

One had no shoulder left. The doctor with us said, ‘There’s nothing I can do.’

‘But look, he’s talking, asking for help…’

‘It’s possible, would be possible to save him, but not with what we’ve got.’

And every day, every day it carried on like that. They just kept on bringing people. ‘It’s too late for an injection. We’ll have to operate.’ And people endured it, watched, wanted to live.

‘I went out to drink some tea and a shell hit. Everyone died. I was standing alone in that kitchen and only my leg was injured. That’s it. My son, his fiancée, my grandson, my wife. They were sitting there smiling just a minute ago. And now there’s no-one left. They’re all dead.’

‘My husband and I lived on the fifth floor. The middle floor. We have a daughter and a one-year-old son. My husband grabbed our daughter and I grabbed our son. We pressed ourselves against the wall. I turned around, and only my husband’s head was left on my shoulder. My son survived, he’s got a broken hip.’

‘I tried to dig my sister out of the rubble at the Drama Theatre. For several hours. She was sitting almost directly under the chandelier. The chandelier fell. There were so many people there when we arrived. With kids, babies. And when I came out, it was just… We couldn’t reach them. The walls had collapsed. From the whole section where there were 200 people, let’s say, we dug out three alive. And that’s it.’

We went out every so often to see who was there. If someone was more seriously injured we took them. I saw a guy standing there in a T-shirt in the freezing cold. With both hands bandaged.

‘What’s wrong with your hands?’ I asked.

‘I can wait a bit longer. I’ll queue.’

There were women and children. So he stood and waited.

Forty minutes passed. He was still queuing.

I asked again, ‘What’s wrong with your hands?’

‘A shell exploded. I fell to the ground,’ he said.

What do people usually do? Cover their heads. But in panic he’d splayed out his fingers like a rooster’s comb.

‘Look,’ he said, ‘I bandaged them up. I don’t even know what’s underneath.’

When he opened it up and we took a look – Jesus. We had to amputate. But with what? You can’t just saw off seven fingers with a knife.

We found something, knew there were some secateurs. We cleaned him up. Got to work, one finger at a time. They gave me the secateurs and said, ‘Do it like this, so the skin gets pinched together afterwards. Make sure the bones don’t stick out sharply.’ And I sat there as if I was using nail clippers.

‘It’s fine,’ he said. ‘I can bear it, it’s fine.’ But he was shaking. He did really well. He had shrapnel in his back and those fingers. He came back again to change his dressings. Then they decided to flee as a family, they didn’t stay with us.

There was a woman called Zhanna. A very beautiful woman. Her husband brought her, said their child had died – 4 years old. She had a wounded hand, something beneath her breast, a broken hip, a huge haematoma. Huge. She was so beautiful, we were in awe. She didn’t open her eyes, she had amazing eyelashes, beautiful skin. And we knew that she would die. Because she needed an operation on her head. And we couldn’t do it. We took such care of her. She came to. Told us her name and surname. And that was it. She didn’t regain consciousness, didn’t move.

She started breathing with her stomach. She changed, her breathing changed. Her sweat was sticky. It was clear that it was the end. She died the next morning.

It took us three days to take her outside. We couldn’t carry her under the shelling. We tried to carry her, attached a piece of film to her body saying who she was. We’d try to carry her, the shelling would start, we’d go back. But we couldn’t just leave her. We had to move her. There was a kitchen in the grounds. A separate building. The kitchen got hit by a shell too. But at least the walls stayed standing. The roof was gone. We carried the bodies there. Because there were so many corpses.

Amputated arms went there too.

When it quietened down again, we went outside and there were just masses of corpses. Small children. I looked and saw a child with no head. I got fixated on it. I really wanted to find the head. But I couldn’t. So we wrapped her up. A stranger. Because of course we didn’t know who she was. There were so many like that.

We couldn’t figure out what was wrong with Anya’s knee. It just wasn’t healing. A decent amount of time had passed and it wouldn’t heal. In the end it turned out a piece of shrapnel was stuck in there. When it came to the surface and we got it out, the wound more or less started to heal. She’d given up hope of finding her child, it seemed. I guess she’d come to terms with it. But we’d hoarded so many nappies, so much formula.

‘Why the hell do we need formula?’

‘It’ll come in useful, everything will,’ I said. People came and took it with them.

In the end – can you believe it? ¬– some people came for formula. And told us that there was a newborn without a mother in another basement. They brought the child – ‘Is he yours?’ ‘Yes, he’s mine’. ‘Damn,’ I said, ‘how is that possible? How?’ Not knowing whose child it was, someone had simply grabbed him. A newborn. Miracles do happen… But rarely.

After that it was so good. People came to have their dressings changed and brought things with them. A guy came and brought a fish. Ohhh, he’d only just caught it. ‘I’ll go and clean it,’ I said. We lit a big campfire and had a feast. Fried fish, fish soup. Everyone was so happy.

We worked like triage in A&E. Recorded everyone’s details. Asked where they’d been injured, under which circumstances, their home address, surname, first name. When they’d arrived and when they’d need their dressings changed.

Young Sashka started getting better. I helped him through. If he needed an injection, he’d go, ‘Hold my hand, please’.

His collarbone was shattered and he was covered in holes, the poor thing. But he so wanted to live. He started sitting up. He started eating.

His dad came and said, ‘I’m taking him.’

‘Don’t, don’t go. There’ll be shelling in a minute.’

We already knew what time it started.

The shelling started around half past five and ended around half past three. It was constant. Only a short break for lunch. So you could travel around lunchtime, at least for two hours. And we knew that they wouldn’t shell our side then. I mean, you could catch a stray bullet anytime. But it wasn’t like when there was shelling.

Sashka’s dad took him. Put him in a wheelchair. They walked about 60 metres from the bunker…. Then the shelling started. Shrapnel slashed through Sashka. Black smoke and white stuffing from his puffer jacket.

Sound of a dog howling. Scrabbling.

Our yard dog howled for a really long time. Then she left us. For good. The most horrifying thing was that we couldn’t go out there. We couldn’t go and get him. He sat there in that wheelchair for a week. His father ran away. There was nobody at all with Sashka.

Then it quietened down. People stopped coming. Nobody thought there was anyone left in our district. The soldiers wouldn’t let them through. People would say, ‘They’re there, they’re treating people.’ ‘No.’ And that was it. Well, power had changed hands. We realised that we needed to make contact with them somehow. We needed to send people away, evacuate them. Get them treatment.

And I needed to find my daughter. I hadn’t had any contact with her for those one and a half months. None at all. The things that went through my head.

‘Why would they bring her in wounded?’ the doctors asked.

‘What am I supposed to think when all this is going on?’

Just imagine – they brought in a girl. And she was covered up, curls like my daughter’s, the same colour hair. I looked at her in the half-light: her legs, they looked like mine. Her head rolled to the side and I saw – the child had no face, it was gone. She wasn’t even bleeding. Nothing in a horror film could compare. Just white flesh. I could see everything: teeth, muscles. I nearly lost my mind.

The doctors said, ‘Don’t worry, it’s not her. Her mother’s with her.’ But I didn’t believe them. Maybe they just don’t want to tell me, they’re trying to calm me down. Maybe this woman just said she was the mother so they would take her. I walked up to her and sat down. Asked her daughter’s name.

‘Karina.’

My hair nearly turned white. She’s mine, my child’s called Karina.

‘Are you really her mum?’

She didn’t even seem to hear the question.

‘I was sitting next to her. Why did nothing happen to me but my child has no face?’

Then I went to see those Russian soldiers. I planned to ask them. Because I’d heard there were some kind of lists. Of the living and the dead.

They pointed me towards the man with the lists. He was imposing, obviously there for a reason. One of the high-ups.

Well, what could I do? I went up to him. Asked about my daughter – nothing. She was nowhere to be found. Not among the living, not among the dead.

I wondered whether I should mention my ex-husband or not. I just knew that he’d kill me. I needed to find my child. He had connections, he could find her. I threw caution to the wind. I said his name.

And it turned out I had stumbled upon someone who knew my ex-husband.

Can you imagine? Just like that.

And he said, ‘They’re looking for you. At the morgues, everywhere. Let’s go.’

‘I’m not going anywhere without my elder daughter,’ I said. ‘Until I know that she’s alive.’

‘At least let us know where to find you. Write a note so he’ll believe that you’re alive.’

I wrote the note.

He came by in the evening. I knew that he was coming for me and that it was definitely about my daughter. Once again I was afraid to look at his face. I was terrified. I stood up so tentatively and thought, I can’t even go up to him. I’ll run away. I went outside and he said, ‘Your daughter’s alive.’

‘Is she in one piece? Where is she?’

‘In Donetsk. It’s safe there. She’s okay.’

It turned out that my elder daughter had escaped after a month. They’d seen that there were kids there, five of them. And crammed them into a car. They waited there for 13 days. In a field. The road, the field, the shelling. The fields were mined. The sole of her foot was burnt in her trainers.

I was so happy. I can’t express it in words. It was a miracle. Just a miracle. For some reason I had got very lucky once again.

‘I’ll go to hell and back now, I don’t care,’ I said.

They evacuated a lot of people. Because there was no time to lose – they needed medical attention. The only ones who stayed were the families of the two doctors and people who didn’t want to leave. The two possible destinations were Donetsk or Russia. There were no other routes. People tried to leave on foot. Can you imagine? Going to Zaporizhzhia on foot – that’s 200 kilometres. We only found out when they crossed the border and made it alive.

Well, I left too. They took me to Donetsk. My ex-husband met me.

They say that people don’t change. Now I think that it depends on the circumstances.

It turned out he didn’t know we were in Mariupol. He thought we were with my brother in Lviv. He suddenly realised when he lost contact. With all of us. ‘It’s like I could sense it,’ he said. He saw a video of an eight-year-old girl dying. They were driving her to the hospital. He got so obsessed, kept saying, ‘That’s my younger daughter. I can see her. That’s my daughter.’ He searched everywhere. At the morgues, everywhere. He found the doctor from the video. And the nurse. Tracked them all down. Turned everything upside down. Not a trace. Mentally he buried his children.

He was a shadow of his former self. I even managed to raise my voice at him. I said that we would not under any circumstances stay in Donetsk. And he agreed. ‘Go,’ he said.

When I was praying in the bunker… well, talking, not praying, I wondered, why did we get separated? And then it hit me – if there’d been three of us, one of us would have died. Because it’s Russian roulette.

According to official data, 87,000 people died in Mariupol. But how many more are still unidentified, disappeared without a trace, buried under the rubble of apartment blocks?

Before 24 February, 430,000 lived in the city. Which means that approximately every fifth person died.

September 2022, Warsaw

Kateryna Penkova is a Ukrainian playwright from Donetsk. She is a graduate of the Kyiv State Academy of Performance and Circus Arts with a degree in acting. Her texts explore the topics of Russia’s war in Ukraine, the occupation of Crimea, violence and sexual harassment, postcolonialism, gender and politics. Her plays have frequently been shortlisted for the Drama.UA festival in Lviv and the Week of Contemporary Plays festival in Kyiv.

Her play ‘Pork’ was among the winners of the 2020 ‘Transmission.UA: Drama on the Move’ playwriting competition organized by the Ukrainian Institute (Kyiv). Kateryna is a co-founder of Ukraine’s Theatre and Playwrights and is currently based in Warsaw.

The two documentary plays, ‘Narrating the War‘ by Anastasiia Kosodii, and ‘A Marathon of Russian Roulette‘ by Kateryna Penkova were first presented on stage at the Camden People’s Theatre, London, on the 4th December 2022.

Both texts were translated by Helena Kernan.

The readings were followed by an in-person discussion with the playwrights, together with project curator Molly Flynn and writer/historian Olesya Khromeychuk. The plays were commissioned by BiGS (Birkbeck Gender & Sexuality), in conjunction with the Ukrainian Institute London and the Experimental Humanities Collaborative Network.

In the eight years between the start of Russia’s war in eastern Ukraine in 2014 and the full-scale invasion in 2022, Ukraine witnessed an impressive boom in socially engaged theatre and political playwriting. These recent documentary plays by Anastasiia Kosodii and Kateryna Penkova exemplify the remarkable culture of defiance and resistance in Ukrainian political playwriting and demonstrate how theatre-makers are using their craft to speak out against the atrocities of Russia’s ongoing war.

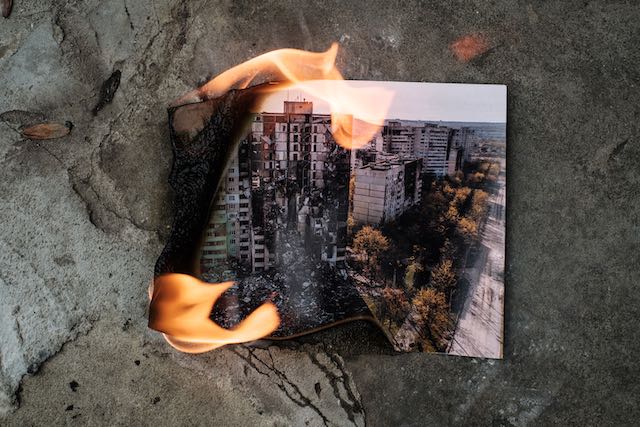

Image: Ola Rondiak, ‘Everybody Knows’ Acrylic collage on canvas.