The Intentionality Behind the Work: An Interview with Christopher Paolini

By Akshay Gajria

Eragon, the first book in the Inheritance Cycle, which established the World of Eragon as we know it now, holds a special place in my heart and my bookshelf. It is the second book I’d ever read in its entirety and where my love for books and stories started. I was around 7-years-old and it left a mark. Fantasy remains my preferred genre of exploration and I’m forever grateful to Christopher Paolini for penning the entire Eragon series.

In 2023, Christopher returned to the World of Eragon with his latest book Murtagh. After reading that, and having attempted writing fantasy of my own, I had several questions about the book, magic systems and his writing process. So, of course, when I got a chance to interview him, I jumped at it.

Christopher Poalini is the author of the Inheritance Cycle (Eragon, Eldest, Brisingr, Inheritance) and creator of the World of Eragon and Fractalverse (To Sleep in a Sea of Stars and Fractal Noise). He holds a Guinness World Record for youngest author of a bestselling series.

This interview is divided into four sections:

Writing Process

A Little Bit of Magic

Book Lore

Book/Film Recommendations

Writing Process

AG: Can you walk us through your typical writing process, from idea conception to finished manuscript?

CP: I could talk about this for a couple hours, if I were really delving into the nitty-gritty, but a sort of a broad overview would be: I get an idea. The idea could come from anywhere. Most of my story ideas tend to involve an image or a scene associated with a strong emotion and it is usually either the beginning of the story or the end of one.

Often it’s the end, which is helpful because it’s difficult to write a book if you don’t know where you’re going. In fact, I refuse to write a book if I don’t know what I’m shooting for for the final scene because if I know what that final scene is or at least what the culmination of the story is, then I can tailor everything leading up to that moment to serve that moment. Whatever that idea is.

Assuming the idea is something that engages my passion and interest, I start developing the characters and the story. This happens concurrently. In the past, this involved a lot of worldbuilding for the World of Eragon or the Fractalverse but now that I’ve created both of those settings, I don’t have to do as much worldbuilding, if much at all. If I’m creating a new setting then I would concentrate first and foremost on how this new setting differs from the real world, specifically with physics, whether that means magic which involves physics or science technology. That will determine what is and isn’t possible in the story from travel times to warfare to politics.

This process could be anywhere from two weeks to two months to longer. But assuming it’s a setting I’m relatively familiar with, like in Murtagh I had the story nailed down in about two weeks fairly solidly. So once I have a good idea of the plot and the characters then I’m ready to write. At that point, it’s just a matter of consistency, patience, persistence. Putting in the hours — assuming I have a good solid outline. Then the writing usually goes fairly quickly. I’ll average about one to three thousand words a day, give or take. At that rate, the first draft of Murtagh took me about three and a half months and that was with Christmas and New Year and a couple of birthdays thrown in there. Not too bad. And that’s pretty much how I tackle it.

Those that would be sort of the broad overview of how I would go about writing a book. The older I’ve gotten the more of these I’ve done the more willing I’ve become to put in a lot more prep work in each book just because it saves me a bunch of time down the road.

AG: Is there any book in the Inheritance Cycle that you did not have an outline for and you just wrote?

CP: No, because I had tried writing stories without outlines before Eragon and I never got past the first five or ten pages because all I had was the inciting incident. Before writing Eragon, I actually plotted out an entire fantasy book and created an entire world for it just as an exercise to see if I could plot out a story. I never wrote that book or story. I just shelved it. (Maybe I should go back to it someday.)

When I decided I was gonna plot out an entire trilogy, I wrote the first book as a practice novel. Just to see if I could and that ended up being the Inheritance Cycle. So even before I wrote Eragon, I had the broad framework of the entire series and I can prove that: If you go back and reread Eragon after he drags his uncle to Carvahall, he has a night of bad fever dreams after that and one of those dreams directly describes the very last scene in inheritance.

Now, the novel that I did attempt to write without a really strong outline was To Sleep in a Sea of Stars. And that’s the reason it took me so many years to write and revise it. I personally cannot plot and write at the same time.

AG: That gives me a very good idea of what your writing process looks like and I’m so glad you touched on To Sleep in a Sea of Stars because in the acknowledgments you state how your sister who read the first draft said that you need to rewrite a bunch of it. I always wondered if the success of Inheritance Cycle changed your writing process or did that make you a lot more conscious about what you are about to write?

CP: Ultimately, it made me more conscious knowing that I have an audience. Knowing that it’s my career and not just a hobby. And also just wanting to be good at it.

AG: Has your writing process evolved because of how well received Inheritance is or do you still stick to the same bones?

CP: Well, it become more structured. The way I approach each story is a lot more organised and I try to be a lot more organised with my thoughts, my intentions. I suppose that’s a good word. Intention. There’s a lot more intentionality behind everything I do because this is my life. This is my career and that’s important to me and I want to write good books. So you’re never gonna go wrong by putting more thought into a book.

AG: That’s a good way of putting it. Intentionality. All of your books since To Sleep in a Sea of Stars are a lot more structured and I noticed this vividly when I was reading Murtagh and also Fractal Noise. I wondered why the initial four books of Inheritance Cycle were not as heavily structured or maybe this was an indication of your growth as a writer?

CP: Now it’s funny, you mentioned that because the first draft of Eragon, or one of the couple of the first drafts actually, had no chapters. I wrote the entire book without a chapter, without chapter breaks because I wanted to provide readers with no excuse to stop. But of course the flip side is that short exciting chapters with little cliffhangers do a wonderful job of pulling people through a story. Thriller writers have known this for ages.

The Inheritance Cycle is very classically formatted. I won’t say structured just formatted, with chapter titles and book titles. There is sometimes a little section breaks when you switch point of views, although later on, I rarely switched point of view within the same chapter, usually one chapter for Eragon, one for Roran.

With To Sleep in a Sea of Stars, I wanted to shake things up. I had read The Dark Tower series by Stephen King and he uses a lot of the formatting tricks that I used in To Sleep in the Sea of Stars, which I liked. Now, with Murtagh, I dialled it back a little from the science fiction. It’s not as heavily formatted. It has has a lot more section breaks though, which I didn’t do in The Inheritance Cycle. Part of that was to just give me an opportunity to do some more maps but also to give the readers a little bit of a break and help the book stand apart from The Inheritance Cycle. But I wouldn’t want to do the full formatted style that I did for the Fractalverse in the World of Eragon. It just doesn’t feel appropriate.

I think for my next book, I’m gonna go with much shorter chapters. I want to experiment with that.

AG: What does your research process look like? Does it change when you’re working with fantasy and when you’re working with sci-fi?

CP: I’ve probably done a lot more research for the science fiction because with fantasy, at least the type of fantasy I write, involves things that we are fairly familiar with in the real world, you know. Horses and trees and mountains and castles and politics and people. Whenever I feel that I’m not familiar with something, I’ll always go spend some time reading up on it to make sure I’ve got some idea of what I’m talking about and I’m not perfect with this. There’s plenty of things I should have done more research on and I only realised after the fact. It’s a balancing act between research and writing time so I just try to make sure I’ve got a good feel for the subject material and then just attempt to be internally consistent with it.

AG: In Murtagh, the dragon and rider relationship was easily comparable to Eragon and Saphira. But at the same time while I was reading it, it felt unique. Was there anything on the craft level that you did to make it feel unique or was it just subconsciously those were the characters?

CP: I made conscious effort to write them differently than Eragon and Saphira and to have their relationship be different than Eragon and Saphira and I got about 80% there on the first draft and then did a lot more tweaking on the second draft to get it even further. I can give you a couple of small examples: Eragon and Saphira will often speak to each other with their minds and Saphira rarely will speak to other people with her mind. She’ll usually speak to Eragon first. And you know, it’s a big thing if she decides to touch someone else’s mind. With Murtagh and Thorn, Murtagh usually speaks to Thorn with his voice. Because he’s always guarding his thoughts even sometimes from Thorn. And Thorn is a little more open to just speaking to anyone who’s around him. Their interaction in general is as I say in the book, it’s more thorny, a little more prickly than Eragon and Saphira and I think Murtagh is a little more protective of Thorn. The relationships are different and that was important for me to try to capture.

A Little Bit of Magic

AG: So I want to switch topics to a little bit to magic. There’s a lot of conversation specifically about hard and soft magic systems. Before I ask you about those I wanted to ask your opinion on what do you think is the purpose of magic in fantasy or any other genre? Why does magic exist in them and why are we so very intrigued by it?

CP: That’s an interesting question. No one’s asked me that before. My gut reaction is that there are many different reasons for having magic in a story. You know, someone could approach magic in a very scientific manner. Brandon Sanderson does it in a very mechanistic manner so to speak. Then there’s magic that’s used like Tolkien’s, which is much more in the mythic vein of things and one could argue that it’s emotional magic, you know, it occurs when it needs to occur. You can’t really logic it. Or maybe you can logic it on a really deep level but that level isn’t shared with the reader explicitly.

Gandalf’s powers come from, essentially God or gods and he’s an avatar and a representative of that power on Earth or Middle Earth. There are limits to it but we don’t know what those exact limits are and that’s always the problem. That old style of magic can be incredibly powerful in a story because it works on the level of emotion. It’s almost like dream logic.

But without the constraints of logic, or mechanics, it’s very easy for it to get away from the writer or the storyteller and it ends up feeling like a crutch. Also if magic existed, then you have to ask does it come from a deity or is it like a naturally occurring thing? And that’s a big division because if it’s from a deity, then you have to think about it differently, but if magic existed then I think that people would want to understand it and they would want to exploit it and they would want to wield it. Then you’re essentially moving into the scientific method.

I always talk about it like exploits in a video game. [Magic is] doing something that is normally forbidden by the rules of the universe and in video games, you see how many people will use exploits and glitches once they discover them. I think people would do the same in the real world if magic allowed for that. You could argue that science and technology is our version of that.

So why do we use magic? Well, it serves a lot of different storytelling purposes. Also a lot of people — I am rambling here, but it’s an interesting topic — a lot of people think about the world in a magical way. It makes sense to include that in a story. But why do we keep coming back for it? I don’t know, I think because it makes the world interesting. To be able to do things that are normally forbidden. Perhaps it also satisfies that emotional logic within us. You’re out walking and a thunderbolt strikes something in a field and you think well, there must be a reason that thunderbolt struck there and boy wouldn’t it be cool if I could use the thunderbolt and the lightning bolt and strike there.

So, I think ultimately it appeals to our emotions.

AG: That that’s a great way of looking at it. I sometimes think of the physics that we have as a hard magic systems that we are just bound by these rules. But we are very keen to try and break them.

CP: I think we lose appreciation for what we have gained through technology sometimes because we get so used to it. I mean we are currently speaking to each other via magic mirrors.

And computers! We took some rocks and we put lightning in the them and made the rocks think.

Right on my desk. I have a light bulb that suspends itself over a magnet. It hangs in the air and rotates and if I were to go if I were to go back a thousand years and show people they would go, that’s magic. They would think our computers are magic and they’re not entirely wrong.

AG: If you’ve ever read The Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan there’s one scene where the character lights his candle with the use of his magic and he just thinks that it’s these small little conveniences that he loves most about the power. Now we have the same thing in smart devices where we can just switch off the light with the tap of a button. Is convenience then, what we look for — through magic or science?

CP: Well, we get so separated because of our technology. We get so separated from the things that actually allow us to survive. Food production, commodity production, resource production, and energy production. There are no rich countries with low amounts of power consumption. Or production. If you look at the graphs of the rich countries, they produce and consume a huge amount of electricity and energy and there is no way around energy. The Industrial Revolution is harnessing the energy of steam and coal and electricity. Without that we don’t have modern society.

I’m going on a tangent here but if we were really truly serious about climate change and about kickstarting our progress as a species, we would embrace nuclear energy left right and centre and until we do I don’t take anyone seriously about saying we got to fix it. We got to fix it, yes but they’re not willing to go that route because that would allow us to advance enormously and especially if in the long term if we’re going to be jetting around in the solar system.

We’re going to be doing it with nuclear rockets because chemical rockets just don’t have enough room. Thank Delta-v for that.

AG: Speaking of energy — in Eragon, you showcase a hard magic system where Eragon has to have enough energy to cast any kind of spell. How did you craft this entire system of magic within the world of Eragon? While you were crafting it, did you have to sort of change any of the story beats because the magic could have just solved the problem?

CP: In retrospect, I would have put more restrictions on the magic system because I find restrictions interesting. They lead to interesting and complicated situations, which are wonderful for dramatic storytelling. I started with the assumption that conscious living creatures and even some non-conscious creatures but living creatures in the World of Eragon can directly control energy with their minds or with their will. Not all of them but you know good chunk of them can do this.

To do anything with that energy requires the same amount of effort as it would to do it via any other means whether it was steam power or your muscles or electricity, whatever. Of course, there is no such thing as energy. It’s electricity. It’s momentum. It’s heat. There’s always a form. There’s not some abstract thing that’s energy. So that was my initial assumption and then everything after that came from those two assumptions. Living creatures can control manipulate energy with their minds and it takes the same amount of energy to do things via any other means. What come after has just been a natural extension of those assumptions. There have been some artificial constraints such as postulating that one of my species bound Language to Magic/Energy in an attempt to avoid the negative consequences of casting a spell and having a wandering thought pop in your brain that alters the intended spell and causes an explosion or something else.

But everything else came from those two initial assumptions and I just tried to follow the logical consequences.

AG: I really enjoyed the extension of the magic system in Murtagh which felt like a coding language. If this happens then that happens. It felt like a natural extension of the magic system and it was great to see that evolution.

CP: Thank you.

Book Lore

AG: In the acknowledgment of Fractal Noise, you wrote about how you don’t want to write anything dark and nihilistic. The first draft of Fractal Noise was dark but you turned it, I wouldn’t say into a happy ending, but you gave it a positive spin. How did you form that philosophy and why do you not want to write a story which ends in a dark place?

CP: Well, I think my philosophy, not my philosophy necessarily, comes from my experience with myself and those I love and watching others. Life is often extremely hard for people. Even those who seem to be living a charmed life often have struggles that are not immediately apparent. I don’t want to make that worse for anyone over the years. I have heard from hundreds and hundreds of readers who have told me that they’ve been touched by Inheritance Cycle, that it helped them in the difficult times of their lives.

Whether that was with depression or grief or any number of other issues. It’s made me think that if a book can help you when you’re in those dark places, then it could just as easily hurt you. I don’t want to be responsible for that. You know, I’m not saying that every book has to be sunshine and roses. Fractal Noise certainly is not sunshine and roses. It is a dark book, but I tried to say something worthwhile and tried to ultimately, if not on sunny note, at least leave it in a place where the main character is starting to move in a better direction. Because I feel like the great challenge of adulthood in many ways is figuring out how to deal with the adversities that life presents us. Given the societies have become increasingly secular over the years, I actually joked with my editor that Fractal Noise is not a book that would necessarily exist in anything resembling the current form in a more religious society. The question that the main character is wondering would be if it’s God’s will, trust in God, the faith which he could wrestle with. Those questions have a long tradition in literature, but it would be a very different type of book. But if the answer is not one’s faith, then it goes in a different direction. Regardless of how one chooses to ask that question, the real question is how to deal with adversity in life? I still think that question is perhaps the defining question of adulthood in many ways.

AG: Obviously, it is beautifully written. That thud. It has a rhythm of its own which I absolutely enjoyed reading.

CP: Thank you! The funny thing is on Goodreads people are either giving it like one star reviews or four or five stars. People are very very split on the book. And I totally understand. I mean if I didn’t if I weren’t in the right mindset for it, I would hate it, absolutely hate it and also I could see how it could come across as thuddingly obvious to some readers. All of which I think would be fair criticisms. But at the same time, it was one of those things I had to write to get out of my brain. And that was the only way I could write it so…

AG: I’m glad you did. Oh, are there any other one off books that you’re planning?

CP: Many and that’s one of the big reasons for creating the Fractalverse. I want to write books that are not explicitly World of Eragon, so those can go into the Fractalverse. But I also have some big series books in that world that I need to write first, so people have a better idea of what I’m actually doing in the Fractalverse.

AG: When you were writing the the Battle of the Burning Planes (in Eldest), you tweeted that you were listening to Woodkid. Is there any music that you’ve been listening to that inspired scenes in To Sleep or Fractal Noise or even Murtagh?

CP: Nothing that inspired it. But while I was writing To Sleep in a Sea of Stars, I listened to a lot of the Tron Legacy soundtrack. Also, especially the latter part of working on the book, I listened to the soundtrack to the video game anthem, which I know wasn’t a particularly successful game, but the soundtrack is gorgeous, especially like the first half of it. I absolutely loved it, it’s great for writing science fiction.

For Murtagh, I actually went back to stuff I was listening to while writing The Inheritance Cycle. So I was listening to the Lord of the Rings soundtrack. I was listening to Andean folk music which reminds me of the elves. Although there were a few places, I listened to the soundtrack for Aliens, which felt appropriate.

AG: In Murtagh, there were a lot more maps and in The Fork and The Witch and The Worm there was the extension of Alagaesia which revealed a lot more on the east of the continent. Are there more maps?

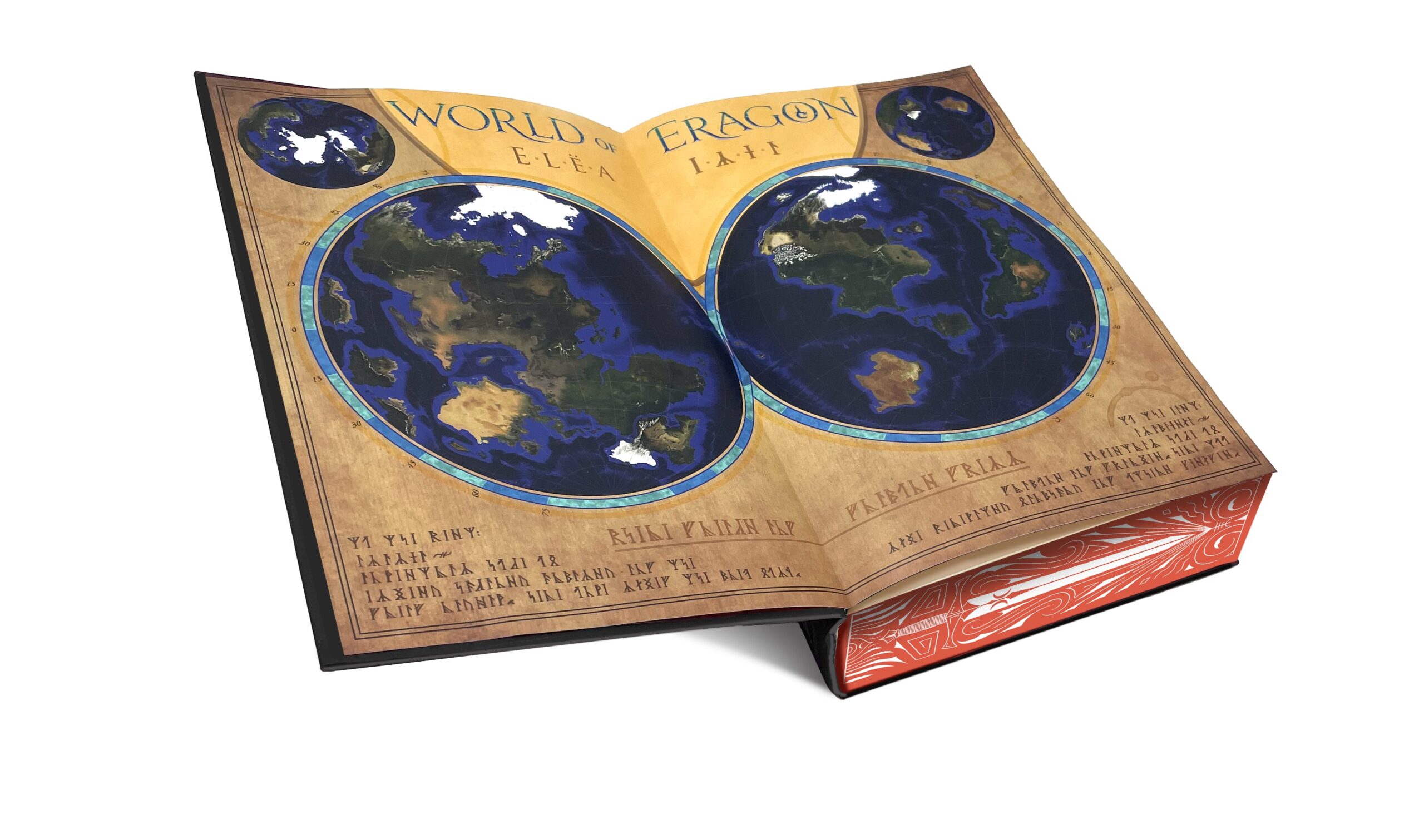

CP: Well, I literally finished this weekend revisions on a global map for the World of Eragon in full colour like a NASA satellite rectilinear equidistant projection. There’s a NASA program that lets you take a rectilinear projection and apply any other projection like this or that and so we’re getting that fixed up and all fancied up for a release later on.

So yes, that’s the big one that hasn’t been released.

AG: Amazing. I look forward to that! Will that be launched as a standalone map or will that be with a book?

CP: It’ll be released as part of one of the additions of the book. I can’t tell you exactly but I’ll share it once it’s actually out in public. I’ll release the map itself, so people can access it. The fandom can have their hands on it.*

AG: I won’t ask you what the next book in the World of Eragon will be but is there sort of a rough estimate when you would want the book to come out?

CP: I would like at least one book to come out next year but I have two television shows in development right now and I am contractually obliged to participate in both the shows. Of course, film and television tends to be all consuming. So I just don’t know how much writing time I’m gonna have for books this year. And that’s just the reality of it, but I would love to have something out next year.

AG: You don’t have to answer this but I wonder will you be writing from Arya’s perspective whenever you write the next book, maybe?

CP: No, not in the next book, but I have a book plan. That’s about 50% her point of view. So I just got to get there.

AG: I’m excited and rooting for you. Aside from the books you’ve planned, there’s this growing genre of fantasy fiction right now which is like cozy fantasy where you have a fantasy world, but the characters are just sitting around in the coffee shop drinking coffee and talking about life. Would you consider writing something in either the World of Eragon or Fractalverse which has a similar cozy vibe to it?

CP: Maybe… but I tend to like stories about exceptional events, epic stories. Fractal Noise is kind of the biggest divergence from what I normally write. When I do Tales from Alagaesia vol. 2, there might be some more of the type of story you’re talking about but the stories that have always appealed to me as an audience has always been, you know epic stories, big stories. And that’s what I’m drawn to writing.

AG: Would you be open to ever in the future opening up the World of Eragon or Fractalverse for other writers to come in and write?

CP: I’ve considered it. I did look at it one point, especially when I was trying to figure out if I could get Murtagh out the door when I wanted to get it out. The problem is I, for good or for ill, have a specific writing style which doesn’t necessarily read like any other author at the moment. It may be something I do down the road, but at the moment I’m still at a stage in my career where I’m just continuing to build the world and building the story of both the Fractalverse and the World of Eragon. That’s something I want to maintain control over.

* The book is the Deluxe edition of Murtagh. See here: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/753245/murtagh-deluxe-edition-by-christopher-paolini/

BOOK/Film Recommendations

AG: Are there any fantasy books you read in the last few years that have stayed with you or you wish you’d have written it?

CP: No, I have been horribly deficient in my reading in the past few years because of the writing deadlines and having two kids in two years. So I read Fourth Wing** recently. In the past few years, Kings of the Wyld*** was fun.

I really haven’t read any fantasy that’s really stuck with me recently. Probably the book that I read that stuck with me was Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy, which kind of reads like fantasy in places? Aside from that I’m reading a book called Traitor. And it’s fantasy. It’s kind of all about trade wars and imperialism. I can’t remember the author’s name unfortunately.

But I read so much fantasy growing up and in teens and 20s and I really would love to read more but I find as I’ve gotten older it’s harder and harder to get into books. And that’s a failing of my own. Perhaps it’s just having read so much and I spend every day writing, sometimes the last thing I want to do is look at more words at the end of the day.

AG: Do you ever listen to audiobooks?

CP: No, no, I hate it. It’s too slow for me. I don’t absorb the language well listening to it for whatever reason.

AG: Fair enough. When you were learning the craft of writing stories, were there any books that helped you understand how to tell a compelling story?

CP: Oh, yeah. I could not have written Eragon without a book called Story by Robert McKee, which is a classic screenwriting book and goes deep into the mechanics of storytelling. And that was incredibly helpful for me because up until that point in my life. I hadn’t really considered the fact that there was a mechanical aspect of story and that one could study it and attempt to master it. That was really responsible for my success to start with.

Since then books that have been helpful are Shakespeare’s Metrical Art by George T. Wright that really helped me with incorporating various poetic techniques into my prose. Other books that I’d read on poetry just failed to answer certain questions. I’d had very technical questions and that book answered them. So I’m a big fan of it.

Then there’s a book called Style by F. L Lucas which to my mind is the best book on prose style that I’ve ever read. [Elements of Style by] Strunk and White have some various inconsistencies and Style is much more organised, much more useful and does a great job of explaining why different eras have different prose styles like the victorians versus other eras. I’ve also read Into the Woods by Thom Yorke and examination of a 5 act story structure. I’ve really enjoyed that because it talks about the 5x story structure which was used by Shakespeare and quite a few others. A lot of playwrights use that. That’s what I did in To Sleep in a Sea of Stars. I used a five act story structure, which is why some readers have felt like it has one beat too many. I did it on purpose to specifically create the feeling that it was almost like a series within one book. It was a longer story than you would normally get with a 3 act structure. A lot of Bollywood films also use the 5 act structure, which is interesting. So I’m I really enjoyed that book.

Also Anatomy of a Story by John Truby. I think the fun thing about Into the Woods is he starts his book by criticising Anatomy of a Story. So there is no one way to write a story but it helps to read all of these books. They have all been enormously helpful and it does help to read about how other people approach that art and craft of writing and storytelling.

AG: Makes sense. I’m Indian and I’ve grown up on Bollywood movies. And is there any Bollywood movie that you’ve enjoyed?

CP: Well, let’s see: DDLJ, Jodha Akbar, Lagaan. I know it’s Tamil, but Bahubali One and Two, Main Hu Na — that’s such a funny film. I’ve seen a lot of Bollywood films. Oh all the Krish films. I mean those are better superhero films than most anything coming out of Hollywood and I love the colours.

I started with Lagaan because it was nominated for the Oscars the year it came out and then after that it was like this cricket match was as epic as any of the fights in Lord of the Rings. I need to see more Bollywood and I am going back to a bunch of the films by Guru Dutt. Boy, those like Pyasa — those are powerful films. If you’re a storyteller, it is helpful to see stories told from different cultures and different parts of the world.

In Western culture, there’s essentially no reason now why two people can’t be together. You’re black you’re white. You can be together. Oh, you’re Jewish. You’re Catholic Oh, you can be together. Oh you’re poor. You’re rich. You can be together. But in Bollywood, well, mommy and daddy don’t approve of this match. Guess what? You’re not getting married. Or you’re different castes or religions and it’s a big deal. It creates such a great conflict for a romance.

Western stories just don’t have that at the moment. We also don’t do romance for men anymore. I’ve watched an enormous amount of Hollywood films. Western films going back to the silent era with classic Hollywood romance movies for men. They used to be: a young man leaves home from the farm and goes to the big city and gets a job. There he meets a nice young woman who’s a sales lady at the store where he’s working. He has to prove himself to her and win her hand and impress her doing something. But it’s from the man’s point of view instead of the woman’s. When was the last romance movie for guys made?

I remember when I showed my wife Bahubali and she was like, oh, it’s a really long film. It’s kind of late in the day. I said let’s just watch a little bit and see what you think. I think that might have actually been the first Bollywood, no, Tamil film that I showed her. We got about 15 minutes in and I look over at her and she’s just locked in. We watched the whole first film. Then she looked at me and said we have to watch the next one. We watch both of them back to back. They are so epic. It’s amazing.

** Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros

*** Kings of the Wyld by Nicholas Eames

Akshay Gajria is a London-based storyteller, writer, and writing coach. He holds an MA in Creative Writing from Birkbeck, University of London and completed his Computer Engineering from NMIMS, Mumbai. He has ghostwritten two books and his writing has appeared in Skulls, The Writing Cooperative, The Written Circle, Bluegraph Press, The Coffeelicious, Your Story Club, Futura Magazine, The Book Mechanic, Poets Unlimited, StoryMaker, Whiplash and more. He usually struggles to finish his sentences… but gets to them eventually.

The Fall Of Troy by William Doreski

A false dawn awakens us.

The right time, when the cloud-facts

explain us to each other

and absorb the spilled light.

An era of rhetorical skies

precedes another great war

with all its pomp and circumstance.

Where will we pitch a tent when

ghost armies occupy our basement

with feint and struggle all night?

You want the sentiments to pile

like rugs from the Middle East.

You want the bass clef to dominate.

I’d rather lie on the sofa

and act as a cat trampoline

while the political class sheds

the last ethical gesture and stands

naked and shameless in the snow.

Christmas may or may not

arrive soon enough to save us

from bellowing little villages

armed with naïve ambitions.

We’ll drive through these places the way

Einstein drove through time and space.

Can we simper ourselves to sleep

for another hour while the clouds

argue among themselves? The fact

of the fall of Troy still lingers.

William Doreski lives in Peterborough, New Hampshire (USA). He has taught at several colleges and universities. His most recent book of poetry is Venus, Jupiter (2023). His essays, poetry, fiction, and reviews have appeared in various journals.

Little Thieves by Susan Gordon Byron

Dali’s clocks were sincere. They slipped over things, slid past and took nothing with them.

They changed. Or I changed them.

Pickpockets.

In the library, while I was staring into space – I had given myself up to laziness, swung in a hammock of not doing – a little gang of clocks slipped down a staircase of books and off the desk. They smothered my words and ran off with a deadline.

I declared Dickens boring. Shakespeare just impassable. With too many princes. I thought nasty things about the librarians, planned for a life without a degree.

I had got quite far into this new fiction when I saw them laughing in the courtyard. They’re not Dali’s clocks, I realised. They’re mine. And I gave chase.

Susan Gordon Byron is a non-fiction editor and podcaster in London. Her poetry has appeared in Dust and tiny wren lit. After a NCTJ postgraduate diploma in newspaper journalism, she worked at the Catholic Herald for two years. She hosts The Culture Boar Podcast.

Breaking Kayfabe: An Interview with Wes Brown

It takes awareness, intelligence and creativity to compete professionally at sport. Its exponents have to process multiple sources of ever-changing information in real-time and react accordingly, trusting their body to back their decisions. It’s arguable sportspeople are not given enough credit for how good they have to be to compete at the highest level; they are judged on post-match interviews and PR-filtered press conferences, and only their counterparts and opponents truly know what it takes to survive and thrive in any given sporting arena.

Some sports are given more licence than others. No one is surprised when a cricketer speaks eloquently about landscape painting, nor when a loosehead prop quotes Greek, but these are sports most readily associated with expensive educations. The wider world expresses amazement when a Rugby League player has Grade 8 piano, or a footballer is studying GCSE Maths. There’s snobbery involved.

Professional wrestling might be the sport we expect least of. For many people, wrestling is Mick McManus fighting Kendo Nagasaki of a Saturday teatime, or a mulleted loud-mouth from Idaho smashing a tea-tray across an opponent’s head. We don’t imagine there are participants deconstructing the sport, examining its many layers of reality, and dreaming new ways to blend its combination of performance, athletics and theatre. There are people who don’t believe it hurts.

Wes Brown is a professional wrestler from Leeds, the son of wrestler Earl Black; he’s also a novelist and poet, and the Programme Director of the MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck. Wes grew up grappling with his brother in his dad’s front room, and piling through book after book at Leeds Modern, the alma mater of Alan Bennett and Bob Peck. His novel, Breaking Kayfabe, published by Bluemoose, is a retelling of his career as a wrestler and his growth as a writer, as he developed his strong style of wrestling and his ‘no style’ of writing.

Were you always a writer?

I began to get creative in my teenage years. I was in a short-lived band that didn’t go anywhere. Film was my main thing. We made a short film that was the only non-funded short film to be included in the Leeds Young Persons Film Festival.

But the bother of getting a location, getting equipment, working with people: it was a logistical nightmare every time I wanted to create something new. It got too much. You could have a vision for a piece but it might require a CGI budget of $700 million, or something ridiculous, yet if you write ‘thunderstorm’ in a story, there it is, a thunderstorm. I realised I didn’t need all those other people.

So that’s how I started writing. I wrote poetry to begin with, and weird genre stuff. I saw an advert for an Arts Council-run writing programme called the Writing Squad, that was open to writers in the North. I got on as a wildcard entry. They’re still going today. It’s become a bit of an institution; all sorts of writers have come through it. There’s an analogy to football, to a youth academy, the idea that you can take people’s skills to another level if you create an intensive environment to support them. Otherwise, they’re left to their own devices.

From the age of 16, I had some poems published through the online version of Sheath magazine, which was connected to Sheffield Uni.

Was that run by Ian McMillan at the time?

It was, yeah. I also had poems published in Aesthetica, and one or two other places. When I was 18, I sold a short story as part of an anthology for Route publishing, who were a Pontefract-based fiction publisher who switched to publishing music books. I did an internship with them. I was quite young – eighteen, the same age as Wayne Rooney. I’d sold a story for 50 quid. I was the Wayne Rooney of the writing world, both breaking through. Nothing could stop me.

And then there was a period in the wilderness where I was experimenting, writing nonsense. When I was 24, I published a novel with a small press. And it was just bad: the novel wasn’t fully finished, I didn’t like the production, there were proofing issues. It just felt fake.

Round that point, there were other things going on in my life. I had a massive identity crisis for a few years, which lasted till I was offered the opportunity to train as a pro wrestler. The Writing Squad offered to pay my training fees, so long as I wrote something about it. And I thought ‘I’ve got nothing better to do. I’m pretty depressed. I’ll go be a wrestler’.

I got into wrestling training and literally became another person, Or at least, I pretended to be.

Were you still writing?

I went to Birkbeck at the back end of that. Doing my MA got me back on track with fact-based fiction, blending fact and fiction, as I felt that’s where I needed to be. The novelly novels and the fiction I had written felt cartoonish and fake. Birkbeck got me into a space where I felt my writing was a lot better. And that became the book, Breaking Kayfabe.

What was the benefit of the MA for you?

I spent a long time not being able to control my writing. Some good stuff would come out, and some bad stuff would come out, too. And people would be into the bad stuff or pretend to be. I thought people were Kayfabing me. I was thinking, ‘Do you really think this is good? Or are you just being nice?’ I had that doubt.

I was doing what a lot of new writers do, where they want to show that they can write. They don’t write normal sentences, because everything has to be about dazzle. And nobody is impressed. ‘That’s all very well, but tell us a story.’

And it wasn’t until I went through the workshop process on the MA that I realised what people really thought, and found I knew what I wanted to do.

Describe the connection between strong style wrestling and no style writing.

Sometimes I’ve wanted to write in a high literary style, and people have gone, ‘but that’s not you’. It suggests that if you’re southern middle class, you can write like that but, if you’re from the north, you can’t, and I thought, ‘Well, what if I want to have a literary style?’ But on the other hand, there is a kind of truth to it.

And through the MA, when dazzle didn’t work, I developed this new style that I call the ‘no style’ style. I wanted to write invisibly. I didn’t want my fiction to feel laborious. I wanted it to be a rush that I got into, that didn’t feel like writing. Weirdly, people reacted better to ‘no style’. I have a no nonsense, direct, colloquial way of speaking that I’ve grown up with, which I bring to my style of literature. It’s that flatness that makes the style different and literary in a way.

So I wanted to be strong style in the ring. And I wanted to be strong style on the page as well. In wrestling, there’s a phrase that no one’s going to believe it’s real but you want to make people forget that it’s fake. I wanted an MMA vernacular that would be plausible, that would be realistic and would look like it might hurt somebody, something you may use in a fight, to create that reality effect.

And so that’s what the ‘no style’ was. I wanted it to seem spontaneous, to deliberately not write well. And that was a risk because if you want to purposefully write with a little bit less gloss and a little bit less polish, it could come off like you just can’t write. But I wanted it to be a bit rugged, you know.

William Regal is a British wrestler who trained people in a WWE Performance Centre. For him, the aesthetics of good wrestling should be a little ugly. It shouldn’t look too choreographed. It shouldn’t look too clean, because it should still look like a proper fight. That’s what I wanted in the book. I wanted it to be a bit ugly. I wanted it to be a bit sort of rough and rugged. It wouldn’t be too pristine.

There was a macho man match in WrestleMania 92, or something like that, where they choreographed every single movement in the match. That was largely unheard of at the time, but it went over really well. Over time, that has become the template. Everything’s highly choreographed.

The alternative is to do it spontaneously. You call it on the fly. You feel the crowd. You feel the story of a match and just run with it. And I wanted some of that spontaneity in the book because I love calling it on the fly. In the ring, it adds a sense of unrehearsedness. There’s the thrill of the real.

And with the book, I wanted that flow. I wanted it to flow out of me. And it wasn’t always possible because it’s a difficult state to get into, but I didn’t want to do it in too cogent a way. So for the most part, Breaking Kayfabe doesn’t have chapters, but it’s got collections of scenes that constitute chapters, and I wrote each in one go. I did everything in one sitting. And if it didn’t work, I did it again the next day. I just did it again until I got it. So almost all of it is written spontaneously. I tweaked it a little bit, and the editors added stuff, but by and large, that’s how it came out.

If you’re blending fact and fiction, does that affect the reader’s assumptions about you?

There’s a Nabokov quote: ‘You can always count on a murderer for fancy prose’. And you can always count on a pro wrestler to be an unreliable narrator. They’re slippery and you never know when a pro wrestler is working you or not. That’s one of the joys of the book for me, because people don’t know. I like to see how much have I worked you. This could be a work, it could pretty much all be fiction. It could be a shoot – this is a wrestling term where it’s legit – or it could be a worked shoot, where I make it look like it’s a shoot, but it’s actually a work. Or it could be just a shoot, that I’m pretending is a work. Or it could be elements of all those things.

And people will want to know how much of it is true or not. One reviewer said I was greedy because I was trying to have this pro-wrestling character protagonist, who is also literary, making literary allusions. And I’m like, I am Dr. Wes Brown, literary critic, novelist, programme director of a Birkbeck MA: it would be unusual if I weren’t to think of literature. What am I to do, self-censor, just because he wanted some sort of wrestler who doesn’t think about these things?

Pro wrestling likes to introduce real-life elements, or sometimes real life intrudes into it as well, when people start fighting for real or real feuds come to the fore.

I want that slippery slope of how much of this is real, and never really give a conclusive answer.

At the time I was writing that section, I realised it was about my dad. So, the current protagonist in the story feels like it should be my dad, but actually that’s me. And the bear is my dad. And I let go of the bear, foreshadowing what’s to come. But also at the time, that was a very fictionalised way of dealing with some of these same things.

The whole story is a search for approval – as a writer, from the narrator’s father, from his girlfriend. It’s that about validation and acceptance.

It’s to do with status, and family as a micro society. You’ve got your own status in there: I’m now really important to those people. I’ve got people who depend on me, who I need to take responsibility for. I’ve got people I need to, in the best possible manner, be a dad for. I need to be a husband. I need to be a more whole person. Status is huge.

And I think, coming from a lower social status, and having difficulties in your upbringing – it’s not directly coming from my parents, but from circumstances as well, that you weren’t really wanted. Nobody really thought anything of you. It was all polite and there’s nobody really actively discriminating against you, it’s just nobody thought you were special. You were nobody’s favourite.

And you wanted to be the man you want to be. You wanted to be the champion. And then growing up in the big shadow of somebody like my dad: when you’re the son of a wrestler, that’s all you are.

What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a true crime book about Shannon Matthews, who was kidnapped by her mother. This happened in Dewsbury, not far from where I grew up.

The book started out as faction, as a David Peace-style story, which had the same themes as Shannon Matthews’ story, but which was not specifically about her. But I could never make it work.

And then I tried to make it an oral history, like Norman Mailer’s Executioner’s Song, but I found nobody in the community would talk to me.

I ended up doing it as some sort of true crime thing. I was worried it would be artless, merely a document of what happened, but actually, what I’m finding is, in writing this way, even though it’s nonfiction, all my skills as a novelist are coming to the fore. I’m trying to let the story come through the characters as the events happen, so the tension builds and any reflection or knowledge is revealed naturally. I’m not necessarily going into the heads of the characters because obviously I don’t have access, but you can safely assume that say, this person finds out this given fact at this given point. And I’m gradually pulling the story out, like a string, and not just bombing everything with exposition and knowledge and opinion.

I moved to this format because I wanted it to be as real as possible. I wanted nothing to be fictionalised.

That’s why it’s taken me 13 years to write it.

Breaking Kayfabe is published by Bluemoose Books

CRAIG SMITH IS A POET AND NOVELIST FROM HUDDERSFIELD. HIS WRITING HAS APPEARED ON WRITERS REBEL, ATRIUM, IAMBAPOET AND THE MECHANICS’ INSTITUTE REVIEW, AS WELL BEING A WINNER OF THE POETRY ARCHIVE NOW! WORDVIEW 2022.

CRAIG HAS THREE BOOKS TO HIS NAME: POETRY COLLECTIONS, L.O.V.E. LOVE (SMITH/DOORSTOP) AND A QUICK WORD WITH A ROCK AND ROLL LATE STARTER, (RUE BELLA); AND A NOVEL, SUPER-8 (BOYD JOHNSON).

HE recently received an MA IN CREATIVE WRITING AT BIRKBECK, UNIVERSITY of london.

TWITTER: @CLATTERMONGER

I Have Nothing New To Say by Sinéad MacInnes

On your whistle-stop tour of the Highlands

and Islands our whispers are said

to be heard by native ears

O Dhia

dè rinn iad?

Oh God

what have

they done?

Aon.

One.

The Barabhas moor on Lewis is empty.

Leòdhas – far an do rugadh mo sheanair

Lewis – where my

grandpa was born

I have nothing new to say. And yet

perhaps I echo the emptiness they pronounce

as they roll in brazen on bulldozer. As if it is a tank.

Nothing to see here! No sign of life.

The shaft of ephemeral light hits the same spot

on Donald-John’s rowing boat at the same time of day,

each day this season, as we continue to live

in the shape of our shadows, lapping against low tides.

Dhà.

Two.

Uibhist a’ Tuath – far an do rugadh mo shinn-seanmhair

North Uist – where

my great-

grandmother

was born

My grandpa sits atop a rock on the Cnocaire at number 10, Bàgh a’ Chàise/highest hill point above the croft/I am small enough then to still be sat atop his knee.

His walking stick props up the rock next door to our stone throne

its head gracefully carved by Duncan Mathieson of Kintail

into the face of a bird

whose wife force feeds me biscuits and strokes my cheeks

(Duncan Mathieson’s wife does, not the graceful bird walking stick),

twice a year when visiting on our way home to croft from city,

Duncan Mathieson being distant cousin on my grandpa’s father’s side

this delicate web of sloinneadh they trace

through every ceilidh as we sit in their tiny dwelling

set into mountain face of a cleared valley of

broken and uninhabited homes and

listen to the last of our tradition-bearers spitball stories that

mix with tinkling laughter,

peat and cigarette smoke and reverberate round the room.

We drive away. A sad echo

follows us through the Glen.

Now, back on the Cnocaire we survey our Kingdom,

mo sheanair and I, the sea on three sides.

Nothing between here and Canada, a Shinéad, dìreach ocean.

I imagine I am falling off the edge of the world right into its centre.

Gusts of wind blow my hair across my face

grandpa hums the Addams Family theme tune,

we giggle. He squeezes me tighter against the breeze, points,

seall air an sùlaire. Dreamily we watch gannets dive for fish that way they do,

high up at our hilltop-eye-level, they circle,

we watch in wait – and then

– a sudden plunge! Turning like a whisk as they plummet down

into quiet splash, we yelp in delight spotting squirming fat fish in its beak

I ask, small chin tilting up to his,

how can they see under the water from all the way up here?

Survival, he replies.

With a slight shake of his head.

Trì.

Three..

I have never seen anything more unpropitious

– said Sir Walter Scott of the Harris skyline (from his boat)

Beàrnaraigh na Hearadh – cò às a thàinig mo sheanmhair

Berneray, Harris –

where my granny

came from

They made maps with no place names

numbers instead, to demolish

our townships, already poor in soil

now drifting nameless through their cache

In this desolate land

Eyes flash cash, hand grips stick, miss what sits

in front of them/hold on to your breaches boys and away we go!

Screech into hearth holding hearts encased in stone

bleed out into rich purple heather staining it brown

Sinéad, come on, time to move on – I – flinch/gut/choke on my own knowing/freeze in disappearing/shout or run/shout or run/shout or run/I –

swallow. Hundreds of years stick fast in a throat taught to sever our speaking,

to dance carefully round drunken hopelessness. All in the past.

Sit quiet/feel the weight on my chest/moors burn/flames lick hot on our backs

And you do not exist.

Ceithir.

Four.

O Dhia/Ar n-Athair a tha air nèamh

Oh God/Our Father

who art in Heaven

Cataibh

Sutherland

where great grandfather, the minister,

and great grandmother, the healer, are buried,

far from home, dead amongst the ghosts

of 7,000, never to return.

Run over our bones until they turn to dust and you can say – See?

It’s empty here.

Hear the psalms swell we call and we respond

wrapped in shrouds of bitter judgement

pray our resistance away/arrive starving from Barra

shock the city/draped in the famine they made.

Coig.

Five.

Cò as a tha thu?

Where are you from?

Literal translation

who are you from?

The land springs forth the people

not the other way round

so remote, how wild,

so rugged, how free

freedom is in the eye of the beholder when

they proclaim the people of a place are pretend.

Sia.

Six.

My mamaidh, mo mhathair, text me yesterday,

Six eagles circling over Bagh a Chaise this morning with a golden moon

going down in the shell pink Western sky

Eagle emoji eagle emoji

Shell emoji

Love heart

Tha gaol agam ort

I love you

Literal translation/I have love at me on you

sits between us/as eternal offering.

all the men in my story are dead now.

land was never meant to be a possession

and I have nothing new to say

nothing I could translate into this tongue, anyway.

**

For all erased and dispossessed people and lands.

Many thanks to Catrìona MacInnes for the photos and to Fiona MacIsaac and Yvonne Irving for checking over the Gaelic

Sinead MacInnes is a writer, facilitator, actor and performance poet based at Birkbeck, University of London, where she is studying for an MA in Creative and Critical Writing. Her work straddles the creative-critical seam, exploring shame, trans generational trauma, colonial legacy and the Gaelic world

‘A defining message of education and acceptance’ : Dale Booton in conversation with Matt Bates on his debut poetry pamphlet, Walking Contagions.

MB: Walking Contagions strikes me as being not just a beautiful suite of poems, but also a political act through its – to quote the blurb – ‘defining message of education and acceptance.’ How did you begin to conceptualise the collection and where did your research take you?

DB: When I accepted my own queerness in my late teens, I went on an research expedition into queer history. Obviously, a huge part of recent history has been the AIDS epidemic. It has been a medical, emotional, social, economic, and political topic for so many including those we have lost, and those living with HIV/AIDS who are still stigmatised today. I read everything I could on the subject and watched as many documentaries and films as I could. I just wanted to know everything, nerd that I am! There was a whole history that had been kept from me in education, so I had to find it.

When I sat down to plan the pamphlet, I made so many notes, little scribbles of oh, what about this… or this? I accumulated quite a stack of random pieces of paper, and then, after a couple of my previous poems about HIV/AIDS had been published, I decided to write Walking Contagions. I wanted to mark a journey from the 80s to present day, drawing on the experience of the past to investigate how the medical, emotional, social, economic, and political segments of the epidemic might have changed – or not – over the last few decades. Because I had already written a few poems about HIV/AIDS I didn’t want to just repeat the same content. I had an idea of what I wanted to include: aspects of sexual health, of pain, trauma, a family scene, loss; but I also wanted to have some poems in there that explored queerness in society today as well as the educational side of HIV treatment.

Finding a publisher like Polari has been amazing. Peter Collins, who runs Polari Press, was so wonderful and kind with my work, and Polari have created an amazing cover for the pamphlet. Polari is a queer publisher run by a queer person publishing queer things – what more could a queer writer wish for? The pamphlet I originally sent was very different to begin with, and whilst editing I destroyed some poems completely and wrote new ones because I didn’t like what I had created. Then I sat back down and started to write again, looking at the gaps I thought I had missed, or where I thought I had strayed too far from my concept. My final editing was done over one weekend. I locked myself away in my flat and rewatched AIDS: The Unheard Tapes, then re-read the poems. It took a lot out of me until I was eventually pulled out by some friends and taken out for the night. I just sat in a local club crying, thinking about all those who were lost because society was too ignorant to care and too unaccepting to help.

I wanted to write in a way that was bold, brash and blunt. I didn’t want to overuse metaphor but to say what I really thought on the matter. If my pamphlet expresses an element of the ‘defining message of education and acceptance’, then I have succeeded in what I wanted to do.

MB: A number of the poems are in dialogue with other poets’ works. I really enjoyed the way you use a line from another poet to “push off” into your own poems, offering a multitude of new possibilities by evolving a line. Can you tell us more about this method and how it helped you shape the collection?

DB: I think poets are at their best when they consume other poets’ work, internalise what they appreciate about the poetry, and, – because not everything fits everyone – what they might have done differently if the poem were their own. This is something I have done with various poems and poets’ work, whether that be a specific poem idea or a form, or even just the poem itself. For example, my poem ‘Blood’ is after the poem ‘Blood’ by the wonderful Andrew McMillan, who was such an inspiration when I first started out as a queer poet. Previously, I just rambled on about society and randomness and avoided all ideas of my own queer identity. Reading Andrew’s Physical really helped me to come out of my poetry closet, so to speak. I had moved back to Birmingham for university, I was trying to take my own poetry more seriously, and Andrew’s poetry really helped with that.

So, when I decided that I was going to try and work on more poems in relation to AIDS. The first, ‘Journal Fragments ’82 -’86’, had been published in the We’ve Done Nothing Wrong. We’ve Got Nothing to Hide (2020) Diversity anthology by Verve so I was inspired to keep with the theme. Lockdown had just hit, and I was suddenly very aware of the time that I had to write. I had been re-reading Playtime by Andrew McMillan, which discusses sexual identity, and there is a poem in the collection called ‘Blood’ that I just adored. It explores sex, sexual health, and AIDS history in such a contemporary way. At the time, it had been announced that the twelve-month deferral ban on donating blood for gay and bi-sexual men would be decreased to three months of celibacy, and it really made my blood boil. There was still so much stigma around queer sex and HIV/AIDS, so, I wanted to try educating people about HIV/AIDS through poetry.

I have many friends who are HIV+ and there is still such a lack of education for those that may know little about it. And, sadly, there is still a lot of ignorance within the queer community too. If anything, you should feel safe within your own community, but unfortunately that isn’t always the case. The poems are also for those: the ignorant amongst us who perhaps need some education and reflection of their own. Stigma is dangerous; knowledge and education can help eradicate that. Education is the key, but unfortunately there are people that fight the kind of education that can help save lives, whether that be about HIV/AIDS or about the queer community in general.

I read Arthur Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell in lockdown, which is about love, loss, and the destroyed possibility of happiness as being interconnected with another person. As soon as I read it, I thought of Grindr. I wondered how I might merge the two together in some form; and I ended up keeping the title and stealing the first two lines from Rimbaud’s poem.

I did a similar thing with ‘Exposure, Part II’, taking the last lines of Wilfred Owen’s stanzas and using them in a reconstructed effort to show model the “fighting a war but losing the battle” adage, exploring the onset of the AIDS epidemic with activism and an ignorant government. The poem plays on Owen’s ideals of being neglected by those who you once thought might help you, until you are just sat around waiting for death.

‘Wounded I Stand’ is after زخمستان (wounded-i-stan) by Suhrab Sirat. I fell in love with this broken idea of society and efforts within war that Sirat discussed within his poem. It was for a Young Poets competition – as was ‘Exposure, Part II’, actually – and I started working with the ideas of queerness being broken throughout history by those who want to oppress and eradicate, but still we carry on, we fight on, we love on…because we must.

As for ‘Epilogue’…well, that began in a workshop with the magnificent Joelle Taylor, whom the opening line belongs to – from the poem ‘Got a Light, Jack?’ in C+nto & Othered Poems – and it is one where I left the workshop thinking ooh, I’ve really got something here. It didn’t have a title at first, but as I started editing the poem, I knew it would be about passing on from life, in an oddly sweet and sensationalist manner, rather than some negative damnation of misery. The poem rather encapsulates how I would like to go, looking back at life, love and intimacy, rather than in fear of what is beyond the eternal darkness. Quite a few of the poems throughout the pamphlet are rather morbid, but I wanted to end on a note that was looking back with joy and gratefulness for all the men one has known, rather than regret.

MB: ‘Another Season in Hell’ and ‘Epilogue’ seem to express an acute disappointment with the instantaneous sex-based apps of today (such as Grindr), whilst also feeling simultaneously resigned to them. Do you see there being a tension between digital spaces and the (lack of) physical spaces today such as the bar, club or cruising spaces?

DB: I think that a lot of social activity is now done online – there is no denying it, whether that is merely communication (like Twitter, etc.) or for other forms of gratification (such as Grindr, etc.). We are in a technological age, and that often forces us to struggle with the reality of what is right in front of us. In particular, with recent global events, such as COVID-19 and lockdowns, we have been forced to find new ways to stay in contact with those we care about. Coming out of lockdown and going back into bars and nightclubs, I think there was a bit of shift in how life is approached. I mean, I have seen gay men messaging each other on Grindr while being a metre or so away from one another on the dancefloor and I just think, why don’t you go talk to each other and dance? Then again, I wouldn’t be the person to go up to someone in a club really, either, so, I’m a bit of a hypocrite like that!

I don’t know… perhaps it is a safety net, that idea of possible rejection: it isn’t so bad when it is conveyed in a message rather than to your face. These poems sort of fall into the modern idea of intimacy through anonymity. There is always a risk that comes with social media and dating apps, and sometimes that risk is isolation or mental health issues, but we still use them, delete them from our phones, reinstall them, use them again. It is like a little cycle of hope and despair at finding something in a place that perhaps we know might not be good for us. Like the Rihanna song ‘We Found Love’, we move with the times, and sometimes that means putting yourself out there in ways you never though you might, just as one does with poetry.

MB: Following on from the previous question, I was very moved by the narration in ‘Encounter’ which connects sexual joy to sexual terror under the shadow of HIV. In a state of fever, the narrator sits ‘like The Thinker recounting the faces | of the men I have loved and have been loved by for a night’. There seems to be a further tension on display here between promiscuity and the search for love…can you expand?

DB: Promiscuity is believed to be a very modern idea, and it is also very much connected with the queer community. There is this idea in heterosexual society to find a partner and settle down – but that is utter garbage. Promiscuity has been witnessed throughout history for all sexualities. There is no gene coding for promiscuity. Levels of promiscuity change through a person’s life and emotional states. Some people may have sexual intercourse with one person in their life, others may have sexual intercourse with thirty, seventy, three hundred. Neither is a problem – so long as you are knowledgeable.

By this, I mean, safe sex, regular sexual health screenings, communication with the partner. Promiscuity may have been scarier during the onset of the AIDS epidemic due to the risk that was associated with it, as well as the stigma that wasn’t only caused because of AIDS, but because of the sexuality it was most closely aligned with. However, I do believe that fear has led to queer people being more educated on sexual health than perhaps a lot of heterosexual people. Often, as I have discussed with numerous university friends and secondary students, because a lot of heterosexual people believe that sexual health isn’t something for them to worry about. There are times when students have said to me: “Only gay people get sex diseases.”

Education is a tool, but often it is not being used correctly. Relationship and Sex Education (RSE) has come a long way, but it still has so much further to go, and poetry can help with that. I wrote ‘U = U’ after a conversation with a HIV+ friend of mind, and they described the virus as being trapped in a rosebud that doesn’t open, which I then took, used, and developed. I did an assembly for World AIDS Day last year at my school, and I was deeply shocked by the minimal information at hand, lack of understanding, and, indeed, tolerance around HIV/AIDS from staff alone. Undetectable means Untransmittable, and that is a message RSE and Biology lessons need to reiterate.

As for love – I wouldn’t say I am very successful with that topic. My poems – although they do have romance throughout them – often fail to attribute anything to anything as definitive as ‘love’. But maybe that is what love is – as it is very different to everyone – an undefinable abstract that is woven throughout what we do, rather than projected and instilled in one person or poem. Within ‘Encounter’, perhaps it is that desperation for love that defines the speaker: I am fully aware of my longing for love in my youth, of the desire to fall head-over-heels for a guy, to feel a connection…but, it doesn’t always work out that way. The poem holds that anticipation and fear of what comes next? especially for the poem’s setting in the AIDS epidemic.

MB: I love how this collection of poems is in dialogue with the past, present and future. Focusing on the past, for a moment, I was reminded of Heather Love’s (in Feeling Backward: Loss & the Politics of Queer History) argument that narrations of queer suffering are an embodiment of queerness itself. For Love, texts that narrate queer suffering and ‘insist on social negativity’ can be useful because they ‘underline the gap between aspiration and the actual.’ How do you feel your collection both memorialises the past and articulates a hopeful future?

DB: For me, history in words is a current we have captured, contained, and given a new home. My pamphlet is a little home – it houses change as well as lack of change. To me, queer history is an essential part of growing up as a queer person, no matter when you are born. Perhaps I’m just a nerd but I think that you need to know the history of your own community.

At school, you are taught history – often flawed and Eurocentric – but history, nonetheless. Why then, when you discover who you are, do you not want to know that history, too? There are many young queers oblivious to the history that our queer ancestors have fought through and for us in order for the freedoms we have today, and that fight still goes on. I can’t understand how you wouldn’t want to know about all that. It should be taught in schools as a part of history. I know that in the school I taught at, there wasn’t even an LGBTQ+ History Month until I developed a scheme for it; and that was in English, not History. Queer history is a part of history, so it must be taught.

While my pamphlet mostly deals with HIV/AIDS, there is a current of development and change within society. For example, the development of treatments has meant people living with HIV can live long, prosperous lives…something that those in the 80s didn’t have. Education and activism are the couple that can end the stigmatisation of HIV/AIDS around the world, which is exactly what we need. As I said before: Undetectable means Untransmittable. Education is the key.

MB: More generally, which poets do you particular admire and draw inspiration from?

DB: As I said earlier, a huge inspiration for me has been Andrew McMillan and to whom I am very grateful to for blurbing my pamphlet. He has been very kind about my work, and he is someone I always go back and read. Andrew also introduced me to the work of Thom Gunn and Mark Doty, both of whom have been inspiring. Their exploration of the onset of the AIDS epidemic, of loss, but also of love, is actually really chilling. Their poems aren’t poems that are quick to leave you.

I mentioned Joelle Taylor, whom I adore. Jemima Hughes. James McDermott. Caleb Parkin. Mary Jean Chan. Ocean Vuong. Jericho Brown. Danez Smith. Fiona Benson. Raymond Antrobus. These are all poets I constantly go back to, are constantly re-reading and they aren’t all queer. They each have a different purpose to me, if that makes sense. For example, if I am writing about mental health, I return to Jemima Hughes; if I am writing about family, I re-read Mary Jean Chan or Fiona Benson; queerness…I have a whole deck of poets to keep going back to and re-reading. I always try to think: What have they written? What haven’t they written? What can I write?

I also have some poetry friends and acquaintances that I draw inspiration from such as Piero Toto, Simon Maddrell, Stanley Iyanu, Juliano Zaffino Ashish Kumar Singh, Luís Costa, JP Seabright. These are people I talk to about poetry: their own, my own… or some that I just read the poetry of and adore.

MB: Finally, what’s next for you Dale, writing-wise?

DB: I am currently editing a second poetry pamphlet, which will be published with Fourteen Poems early next year, exploring queer friendship and nightlife. It is kind of based around some of the events in the past two years of my life, moving away from a relationship and falling into a safe queer space. I haven’t really written any poetry in a while, so it is good to push myself back towards it through some editing.

I also have an idea for a novel, but that is something that will need fleshing out before I start writing it. Hopefully, in the near future, it will become a little clearer in my mind…

Dale Booton (he/him) is a queer poet from Birmingham. His poetry has been published in various places, such as Verve, Young Poets Network, Queerlings, The North, Muswell Press, and Magma. His debut pamphlet Walking Contagions is out with Polari Press; his second pamphlet is forthcoming with Fourteen Poems in 2024.

Twitter: @BootsPoetry

Matt Bates is the Poetry Editor of MIR.

Neptune’s Projects: An Interview with Rishi Dastidar

Neptune’s Project is the third collection of poems by the poet and editor, Rishi Dastidar. It looks at climate breakdown from the point of view of Neptune, the Roman god of fresh water and the sea. It is published by Nine Arches Press.

What’s your background as a writer?

Briefly, as I have been at this lark for a while: lots and lots of student journalism, then a failed dabbling with actual journalism for a few years, before I discovered copywriting for advertising and brands. While that was (and continues) to pay the bills, I was trying and failing to write fiction, and trying and failing to write essays. And then when I was about 30, I discovered poetry. Still failing at that, but remarkably, readers appear to be prepared to join me as I do.

How did you get into the concept behind Neptune’s Projects? What were the stages in its development? How did you settle on the idea of using the voice of a God to explore the destruction of the planet?

There was no planning or forethought. About 2018 or so, a few poems emerged that had the sea at their centre, as an object to be ruminated on (not much like what I was writing at the time) – sea as confessor, sea as destination to bring lovers together. And then when ‘Neptune’s concrete crash helmet’ arrived, that was when a light bulb went on: is there something in adopting the voice of a god, but giving him very human qualities and frailties? It turned out that adopting a persona that revolved at once about both being powerful and powerless was a great parallel for exploring subjects like climate change.

I should stress: I didn’t set out to write eco-themed poems; they came from this voice, and diving into it. Clearly my subconscious was worrying away, but it wasn’t like my conscious brain was telling me: you must write this. The book is a result of some of my far more submerged fears rising without being bidden all that much.

What can poets hope to achieve in the fight against the destruction of the planet? Do artists have an obligation to contend with the issues of society?

On the latter question: no, they don’t at all, and I’m not going to go round telling other artists what to be concerned about. But for me, as someone living and working in a society that feels – is – fucked up in so many ways, but with so many wondrous things that would have baffled and delighted our ancestors, too – why would you not want to examine that? Bluntly, I don’t think me and my travails as an individual are all that interesting; I’m far more interested in turning my creative energies and insights on what’s around me, and asking: what’s going on? Are you seeing what I’m seeing? Does this thing make you feel what I feel?

On the former: short of retraining as wind turbine engineers and/or living off grid? Practically – not much. But then: no one ever turned to poetry for policy-driven solutions for anything. We’re here to do what we always have been here to do: to tell stories about who we are as humans, what it means to be humans, to be in the world around us, the one we’ve inherited, the ones we’re making and destroying; and to make some noise about and around all of that. Confirm a few priors, shatter a few prejudices; make people think, look again. Expand the imaginative possibilities for all of us, about how we might live, and not destroy our civilization in the process. All of that helps at the margins of change, I hope. But I’m pessimistic as to how much that actually does to avert the wars and societal collapses that I think we all know are coming. All of us need to pull our fingers out to make a dent in that challenge.

There’s a palpable anger in this collection, but also playfulness and humour. How do you balance the two? Is one a function of the other?

I think so. The balance between the anger and the humour was a happy accident, but the striving for humour was not. It was a very conscious decision I took as Neptune’s voice was emerging. I felt that, through being sarcastic, world weary, through exaggeration, overclaiming and declaiming, maybe even the odd one liner or two, I could access and approach subjects and ideas in ways that I hadn’t see done before in poetry that looked at the environment.

A parallel: from my work in advertising, I well know that humour is a tool, an approach that can be deployed with some success when it comes to raising awareness, attempting to persuade. If we agree that the climate crisis is the most important challenge facing us as a species, why wouldn’t we use every potential tone or shade on the communicative register, to try and reach people? Maybe, just maybe, a black, gallows humour might change a mind or two. I appreciate that might be as useful as giggling into the apocalypse, but I felt – still feel – it’s worth a try.

Are there particular ecologists you look to to help you understand what’s going on in the world?

As hinted at in the book’s subtitle, ‘Now That’s What I call Hyperobject Ballads’, it wouldn’t exist without the work of Timothy Morton, and especially his Being Ecological. I think one of his successes is to show us that we are not separate or unconnected from what is around us. We might think – act – as if we are destined to forever bend the world to our species’ desires. But we’re not. And we’re starting to be able to see that, through the fact that we’re realising that some of what we have created – the hydrocarbon industry for example – is both bigger than we can grasp, and has more ramifications than we realised – emergent, unintended consequences.

I’ve found his way of foregrounding the fact that what we are thinking about is so big that it can’t be looked at in a straight-ahead fashion actually liberating. To me it means that we have to take – and accept – a kaleidoscope of views, approaches, beliefs that we’ll need to save us: which, when you think about how diverse humanity is, isn’t actually all that surprising. Yet it still can feel that way.

What is your attitude to form?