The Intentionality Behind the Work: An Interview with Christopher Paolini

By Akshay Gajria

Eragon, the first book in the Inheritance Cycle, which established the World of Eragon as we know it now, holds a special place in my heart and my bookshelf. It is the second book I’d ever read in its entirety and where my love for books and stories started. I was around 7-years-old and it left a mark. Fantasy remains my preferred genre of exploration and I’m forever grateful to Christopher Paolini for penning the entire Eragon series.

In 2023, Christopher returned to the World of Eragon with his latest book Murtagh. After reading that, and having attempted writing fantasy of my own, I had several questions about the book, magic systems and his writing process. So, of course, when I got a chance to interview him, I jumped at it.

Christopher Poalini is the author of the Inheritance Cycle (Eragon, Eldest, Brisingr, Inheritance) and creator of the World of Eragon and Fractalverse (To Sleep in a Sea of Stars and Fractal Noise). He holds a Guinness World Record for youngest author of a bestselling series.

This interview is divided into four sections:

Writing Process

A Little Bit of Magic

Book Lore

Book/Film Recommendations

Writing Process

AG: Can you walk us through your typical writing process, from idea conception to finished manuscript?

CP: I could talk about this for a couple hours, if I were really delving into the nitty-gritty, but a sort of a broad overview would be: I get an idea. The idea could come from anywhere. Most of my story ideas tend to involve an image or a scene associated with a strong emotion and it is usually either the beginning of the story or the end of one.

Often it’s the end, which is helpful because it’s difficult to write a book if you don’t know where you’re going. In fact, I refuse to write a book if I don’t know what I’m shooting for for the final scene because if I know what that final scene is or at least what the culmination of the story is, then I can tailor everything leading up to that moment to serve that moment. Whatever that idea is.

Assuming the idea is something that engages my passion and interest, I start developing the characters and the story. This happens concurrently. In the past, this involved a lot of worldbuilding for the World of Eragon or the Fractalverse but now that I’ve created both of those settings, I don’t have to do as much worldbuilding, if much at all. If I’m creating a new setting then I would concentrate first and foremost on how this new setting differs from the real world, specifically with physics, whether that means magic which involves physics or science technology. That will determine what is and isn’t possible in the story from travel times to warfare to politics.

This process could be anywhere from two weeks to two months to longer. But assuming it’s a setting I’m relatively familiar with, like in Murtagh I had the story nailed down in about two weeks fairly solidly. So once I have a good idea of the plot and the characters then I’m ready to write. At that point, it’s just a matter of consistency, patience, persistence. Putting in the hours — assuming I have a good solid outline. Then the writing usually goes fairly quickly. I’ll average about one to three thousand words a day, give or take. At that rate, the first draft of Murtagh took me about three and a half months and that was with Christmas and New Year and a couple of birthdays thrown in there. Not too bad. And that’s pretty much how I tackle it.

Those that would be sort of the broad overview of how I would go about writing a book. The older I’ve gotten the more of these I’ve done the more willing I’ve become to put in a lot more prep work in each book just because it saves me a bunch of time down the road.

AG: Is there any book in the Inheritance Cycle that you did not have an outline for and you just wrote?

CP: No, because I had tried writing stories without outlines before Eragon and I never got past the first five or ten pages because all I had was the inciting incident. Before writing Eragon, I actually plotted out an entire fantasy book and created an entire world for it just as an exercise to see if I could plot out a story. I never wrote that book or story. I just shelved it. (Maybe I should go back to it someday.)

When I decided I was gonna plot out an entire trilogy, I wrote the first book as a practice novel. Just to see if I could and that ended up being the Inheritance Cycle. So even before I wrote Eragon, I had the broad framework of the entire series and I can prove that: If you go back and reread Eragon after he drags his uncle to Carvahall, he has a night of bad fever dreams after that and one of those dreams directly describes the very last scene in inheritance.

Now, the novel that I did attempt to write without a really strong outline was To Sleep in a Sea of Stars. And that’s the reason it took me so many years to write and revise it. I personally cannot plot and write at the same time.

AG: That gives me a very good idea of what your writing process looks like and I’m so glad you touched on To Sleep in a Sea of Stars because in the acknowledgments you state how your sister who read the first draft said that you need to rewrite a bunch of it. I always wondered if the success of Inheritance Cycle changed your writing process or did that make you a lot more conscious about what you are about to write?

CP: Ultimately, it made me more conscious knowing that I have an audience. Knowing that it’s my career and not just a hobby. And also just wanting to be good at it.

AG: Has your writing process evolved because of how well received Inheritance is or do you still stick to the same bones?

CP: Well, it become more structured. The way I approach each story is a lot more organised and I try to be a lot more organised with my thoughts, my intentions. I suppose that’s a good word. Intention. There’s a lot more intentionality behind everything I do because this is my life. This is my career and that’s important to me and I want to write good books. So you’re never gonna go wrong by putting more thought into a book.

AG: That’s a good way of putting it. Intentionality. All of your books since To Sleep in a Sea of Stars are a lot more structured and I noticed this vividly when I was reading Murtagh and also Fractal Noise. I wondered why the initial four books of Inheritance Cycle were not as heavily structured or maybe this was an indication of your growth as a writer?

CP: Now it’s funny, you mentioned that because the first draft of Eragon, or one of the couple of the first drafts actually, had no chapters. I wrote the entire book without a chapter, without chapter breaks because I wanted to provide readers with no excuse to stop. But of course the flip side is that short exciting chapters with little cliffhangers do a wonderful job of pulling people through a story. Thriller writers have known this for ages.

The Inheritance Cycle is very classically formatted. I won’t say structured just formatted, with chapter titles and book titles. There is sometimes a little section breaks when you switch point of views, although later on, I rarely switched point of view within the same chapter, usually one chapter for Eragon, one for Roran.

With To Sleep in a Sea of Stars, I wanted to shake things up. I had read The Dark Tower series by Stephen King and he uses a lot of the formatting tricks that I used in To Sleep in the Sea of Stars, which I liked. Now, with Murtagh, I dialled it back a little from the science fiction. It’s not as heavily formatted. It has has a lot more section breaks though, which I didn’t do in The Inheritance Cycle. Part of that was to just give me an opportunity to do some more maps but also to give the readers a little bit of a break and help the book stand apart from The Inheritance Cycle. But I wouldn’t want to do the full formatted style that I did for the Fractalverse in the World of Eragon. It just doesn’t feel appropriate.

I think for my next book, I’m gonna go with much shorter chapters. I want to experiment with that.

AG: What does your research process look like? Does it change when you’re working with fantasy and when you’re working with sci-fi?

CP: I’ve probably done a lot more research for the science fiction because with fantasy, at least the type of fantasy I write, involves things that we are fairly familiar with in the real world, you know. Horses and trees and mountains and castles and politics and people. Whenever I feel that I’m not familiar with something, I’ll always go spend some time reading up on it to make sure I’ve got some idea of what I’m talking about and I’m not perfect with this. There’s plenty of things I should have done more research on and I only realised after the fact. It’s a balancing act between research and writing time so I just try to make sure I’ve got a good feel for the subject material and then just attempt to be internally consistent with it.

AG: In Murtagh, the dragon and rider relationship was easily comparable to Eragon and Saphira. But at the same time while I was reading it, it felt unique. Was there anything on the craft level that you did to make it feel unique or was it just subconsciously those were the characters?

CP: I made conscious effort to write them differently than Eragon and Saphira and to have their relationship be different than Eragon and Saphira and I got about 80% there on the first draft and then did a lot more tweaking on the second draft to get it even further. I can give you a couple of small examples: Eragon and Saphira will often speak to each other with their minds and Saphira rarely will speak to other people with her mind. She’ll usually speak to Eragon first. And you know, it’s a big thing if she decides to touch someone else’s mind. With Murtagh and Thorn, Murtagh usually speaks to Thorn with his voice. Because he’s always guarding his thoughts even sometimes from Thorn. And Thorn is a little more open to just speaking to anyone who’s around him. Their interaction in general is as I say in the book, it’s more thorny, a little more prickly than Eragon and Saphira and I think Murtagh is a little more protective of Thorn. The relationships are different and that was important for me to try to capture.

A Little Bit of Magic

AG: So I want to switch topics to a little bit to magic. There’s a lot of conversation specifically about hard and soft magic systems. Before I ask you about those I wanted to ask your opinion on what do you think is the purpose of magic in fantasy or any other genre? Why does magic exist in them and why are we so very intrigued by it?

CP: That’s an interesting question. No one’s asked me that before. My gut reaction is that there are many different reasons for having magic in a story. You know, someone could approach magic in a very scientific manner. Brandon Sanderson does it in a very mechanistic manner so to speak. Then there’s magic that’s used like Tolkien’s, which is much more in the mythic vein of things and one could argue that it’s emotional magic, you know, it occurs when it needs to occur. You can’t really logic it. Or maybe you can logic it on a really deep level but that level isn’t shared with the reader explicitly.

Gandalf’s powers come from, essentially God or gods and he’s an avatar and a representative of that power on Earth or Middle Earth. There are limits to it but we don’t know what those exact limits are and that’s always the problem. That old style of magic can be incredibly powerful in a story because it works on the level of emotion. It’s almost like dream logic.

But without the constraints of logic, or mechanics, it’s very easy for it to get away from the writer or the storyteller and it ends up feeling like a crutch. Also if magic existed, then you have to ask does it come from a deity or is it like a naturally occurring thing? And that’s a big division because if it’s from a deity, then you have to think about it differently, but if magic existed then I think that people would want to understand it and they would want to exploit it and they would want to wield it. Then you’re essentially moving into the scientific method.

I always talk about it like exploits in a video game. [Magic is] doing something that is normally forbidden by the rules of the universe and in video games, you see how many people will use exploits and glitches once they discover them. I think people would do the same in the real world if magic allowed for that. You could argue that science and technology is our version of that.

So why do we use magic? Well, it serves a lot of different storytelling purposes. Also a lot of people — I am rambling here, but it’s an interesting topic — a lot of people think about the world in a magical way. It makes sense to include that in a story. But why do we keep coming back for it? I don’t know, I think because it makes the world interesting. To be able to do things that are normally forbidden. Perhaps it also satisfies that emotional logic within us. You’re out walking and a thunderbolt strikes something in a field and you think well, there must be a reason that thunderbolt struck there and boy wouldn’t it be cool if I could use the thunderbolt and the lightning bolt and strike there.

So, I think ultimately it appeals to our emotions.

AG: That that’s a great way of looking at it. I sometimes think of the physics that we have as a hard magic systems that we are just bound by these rules. But we are very keen to try and break them.

CP: I think we lose appreciation for what we have gained through technology sometimes because we get so used to it. I mean we are currently speaking to each other via magic mirrors.

And computers! We took some rocks and we put lightning in the them and made the rocks think.

Right on my desk. I have a light bulb that suspends itself over a magnet. It hangs in the air and rotates and if I were to go if I were to go back a thousand years and show people they would go, that’s magic. They would think our computers are magic and they’re not entirely wrong.

AG: If you’ve ever read The Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan there’s one scene where the character lights his candle with the use of his magic and he just thinks that it’s these small little conveniences that he loves most about the power. Now we have the same thing in smart devices where we can just switch off the light with the tap of a button. Is convenience then, what we look for — through magic or science?

CP: Well, we get so separated because of our technology. We get so separated from the things that actually allow us to survive. Food production, commodity production, resource production, and energy production. There are no rich countries with low amounts of power consumption. Or production. If you look at the graphs of the rich countries, they produce and consume a huge amount of electricity and energy and there is no way around energy. The Industrial Revolution is harnessing the energy of steam and coal and electricity. Without that we don’t have modern society.

I’m going on a tangent here but if we were really truly serious about climate change and about kickstarting our progress as a species, we would embrace nuclear energy left right and centre and until we do I don’t take anyone seriously about saying we got to fix it. We got to fix it, yes but they’re not willing to go that route because that would allow us to advance enormously and especially if in the long term if we’re going to be jetting around in the solar system.

We’re going to be doing it with nuclear rockets because chemical rockets just don’t have enough room. Thank Delta-v for that.

AG: Speaking of energy — in Eragon, you showcase a hard magic system where Eragon has to have enough energy to cast any kind of spell. How did you craft this entire system of magic within the world of Eragon? While you were crafting it, did you have to sort of change any of the story beats because the magic could have just solved the problem?

CP: In retrospect, I would have put more restrictions on the magic system because I find restrictions interesting. They lead to interesting and complicated situations, which are wonderful for dramatic storytelling. I started with the assumption that conscious living creatures and even some non-conscious creatures but living creatures in the World of Eragon can directly control energy with their minds or with their will. Not all of them but you know good chunk of them can do this.

To do anything with that energy requires the same amount of effort as it would to do it via any other means whether it was steam power or your muscles or electricity, whatever. Of course, there is no such thing as energy. It’s electricity. It’s momentum. It’s heat. There’s always a form. There’s not some abstract thing that’s energy. So that was my initial assumption and then everything after that came from those two assumptions. Living creatures can control manipulate energy with their minds and it takes the same amount of energy to do things via any other means. What come after has just been a natural extension of those assumptions. There have been some artificial constraints such as postulating that one of my species bound Language to Magic/Energy in an attempt to avoid the negative consequences of casting a spell and having a wandering thought pop in your brain that alters the intended spell and causes an explosion or something else.

But everything else came from those two initial assumptions and I just tried to follow the logical consequences.

AG: I really enjoyed the extension of the magic system in Murtagh which felt like a coding language. If this happens then that happens. It felt like a natural extension of the magic system and it was great to see that evolution.

CP: Thank you.

Book Lore

AG: In the acknowledgment of Fractal Noise, you wrote about how you don’t want to write anything dark and nihilistic. The first draft of Fractal Noise was dark but you turned it, I wouldn’t say into a happy ending, but you gave it a positive spin. How did you form that philosophy and why do you not want to write a story which ends in a dark place?

CP: Well, I think my philosophy, not my philosophy necessarily, comes from my experience with myself and those I love and watching others. Life is often extremely hard for people. Even those who seem to be living a charmed life often have struggles that are not immediately apparent. I don’t want to make that worse for anyone over the years. I have heard from hundreds and hundreds of readers who have told me that they’ve been touched by Inheritance Cycle, that it helped them in the difficult times of their lives.

Whether that was with depression or grief or any number of other issues. It’s made me think that if a book can help you when you’re in those dark places, then it could just as easily hurt you. I don’t want to be responsible for that. You know, I’m not saying that every book has to be sunshine and roses. Fractal Noise certainly is not sunshine and roses. It is a dark book, but I tried to say something worthwhile and tried to ultimately, if not on sunny note, at least leave it in a place where the main character is starting to move in a better direction. Because I feel like the great challenge of adulthood in many ways is figuring out how to deal with the adversities that life presents us. Given the societies have become increasingly secular over the years, I actually joked with my editor that Fractal Noise is not a book that would necessarily exist in anything resembling the current form in a more religious society. The question that the main character is wondering would be if it’s God’s will, trust in God, the faith which he could wrestle with. Those questions have a long tradition in literature, but it would be a very different type of book. But if the answer is not one’s faith, then it goes in a different direction. Regardless of how one chooses to ask that question, the real question is how to deal with adversity in life? I still think that question is perhaps the defining question of adulthood in many ways.

AG: Obviously, it is beautifully written. That thud. It has a rhythm of its own which I absolutely enjoyed reading.

CP: Thank you! The funny thing is on Goodreads people are either giving it like one star reviews or four or five stars. People are very very split on the book. And I totally understand. I mean if I didn’t if I weren’t in the right mindset for it, I would hate it, absolutely hate it and also I could see how it could come across as thuddingly obvious to some readers. All of which I think would be fair criticisms. But at the same time, it was one of those things I had to write to get out of my brain. And that was the only way I could write it so…

AG: I’m glad you did. Oh, are there any other one off books that you’re planning?

CP: Many and that’s one of the big reasons for creating the Fractalverse. I want to write books that are not explicitly World of Eragon, so those can go into the Fractalverse. But I also have some big series books in that world that I need to write first, so people have a better idea of what I’m actually doing in the Fractalverse.

AG: When you were writing the the Battle of the Burning Planes (in Eldest), you tweeted that you were listening to Woodkid. Is there any music that you’ve been listening to that inspired scenes in To Sleep or Fractal Noise or even Murtagh?

CP: Nothing that inspired it. But while I was writing To Sleep in a Sea of Stars, I listened to a lot of the Tron Legacy soundtrack. Also, especially the latter part of working on the book, I listened to the soundtrack to the video game anthem, which I know wasn’t a particularly successful game, but the soundtrack is gorgeous, especially like the first half of it. I absolutely loved it, it’s great for writing science fiction.

For Murtagh, I actually went back to stuff I was listening to while writing The Inheritance Cycle. So I was listening to the Lord of the Rings soundtrack. I was listening to Andean folk music which reminds me of the elves. Although there were a few places, I listened to the soundtrack for Aliens, which felt appropriate.

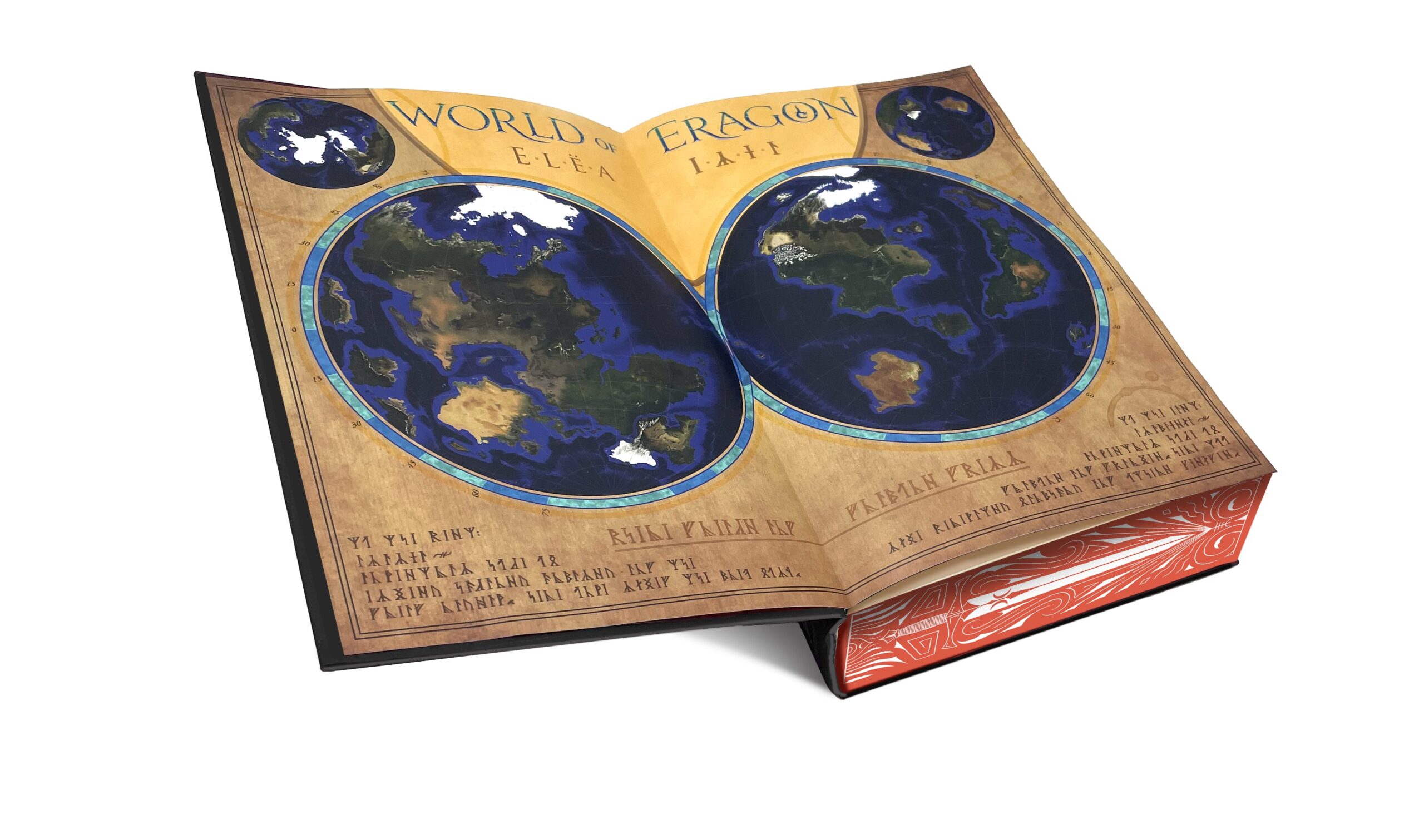

AG: In Murtagh, there were a lot more maps and in The Fork and The Witch and The Worm there was the extension of Alagaesia which revealed a lot more on the east of the continent. Are there more maps?

CP: Well, I literally finished this weekend revisions on a global map for the World of Eragon in full colour like a NASA satellite rectilinear equidistant projection. There’s a NASA program that lets you take a rectilinear projection and apply any other projection like this or that and so we’re getting that fixed up and all fancied up for a release later on.

So yes, that’s the big one that hasn’t been released.

AG: Amazing. I look forward to that! Will that be launched as a standalone map or will that be with a book?

CP: It’ll be released as part of one of the additions of the book. I can’t tell you exactly but I’ll share it once it’s actually out in public. I’ll release the map itself, so people can access it. The fandom can have their hands on it.*

AG: I won’t ask you what the next book in the World of Eragon will be but is there sort of a rough estimate when you would want the book to come out?

CP: I would like at least one book to come out next year but I have two television shows in development right now and I am contractually obliged to participate in both the shows. Of course, film and television tends to be all consuming. So I just don’t know how much writing time I’m gonna have for books this year. And that’s just the reality of it, but I would love to have something out next year.

AG: You don’t have to answer this but I wonder will you be writing from Arya’s perspective whenever you write the next book, maybe?

CP: No, not in the next book, but I have a book plan. That’s about 50% her point of view. So I just got to get there.

AG: I’m excited and rooting for you. Aside from the books you’ve planned, there’s this growing genre of fantasy fiction right now which is like cozy fantasy where you have a fantasy world, but the characters are just sitting around in the coffee shop drinking coffee and talking about life. Would you consider writing something in either the World of Eragon or Fractalverse which has a similar cozy vibe to it?

CP: Maybe… but I tend to like stories about exceptional events, epic stories. Fractal Noise is kind of the biggest divergence from what I normally write. When I do Tales from Alagaesia vol. 2, there might be some more of the type of story you’re talking about but the stories that have always appealed to me as an audience has always been, you know epic stories, big stories. And that’s what I’m drawn to writing.

AG: Would you be open to ever in the future opening up the World of Eragon or Fractalverse for other writers to come in and write?

CP: I’ve considered it. I did look at it one point, especially when I was trying to figure out if I could get Murtagh out the door when I wanted to get it out. The problem is I, for good or for ill, have a specific writing style which doesn’t necessarily read like any other author at the moment. It may be something I do down the road, but at the moment I’m still at a stage in my career where I’m just continuing to build the world and building the story of both the Fractalverse and the World of Eragon. That’s something I want to maintain control over.

* The book is the Deluxe edition of Murtagh. See here: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/753245/murtagh-deluxe-edition-by-christopher-paolini/

BOOK/Film Recommendations

AG: Are there any fantasy books you read in the last few years that have stayed with you or you wish you’d have written it?

CP: No, I have been horribly deficient in my reading in the past few years because of the writing deadlines and having two kids in two years. So I read Fourth Wing** recently. In the past few years, Kings of the Wyld*** was fun.

I really haven’t read any fantasy that’s really stuck with me recently. Probably the book that I read that stuck with me was Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy, which kind of reads like fantasy in places? Aside from that I’m reading a book called Traitor. And it’s fantasy. It’s kind of all about trade wars and imperialism. I can’t remember the author’s name unfortunately.

But I read so much fantasy growing up and in teens and 20s and I really would love to read more but I find as I’ve gotten older it’s harder and harder to get into books. And that’s a failing of my own. Perhaps it’s just having read so much and I spend every day writing, sometimes the last thing I want to do is look at more words at the end of the day.

AG: Do you ever listen to audiobooks?

CP: No, no, I hate it. It’s too slow for me. I don’t absorb the language well listening to it for whatever reason.

AG: Fair enough. When you were learning the craft of writing stories, were there any books that helped you understand how to tell a compelling story?

CP: Oh, yeah. I could not have written Eragon without a book called Story by Robert McKee, which is a classic screenwriting book and goes deep into the mechanics of storytelling. And that was incredibly helpful for me because up until that point in my life. I hadn’t really considered the fact that there was a mechanical aspect of story and that one could study it and attempt to master it. That was really responsible for my success to start with.

Since then books that have been helpful are Shakespeare’s Metrical Art by George T. Wright that really helped me with incorporating various poetic techniques into my prose. Other books that I’d read on poetry just failed to answer certain questions. I’d had very technical questions and that book answered them. So I’m a big fan of it.

Then there’s a book called Style by F. L Lucas which to my mind is the best book on prose style that I’ve ever read. [Elements of Style by] Strunk and White have some various inconsistencies and Style is much more organised, much more useful and does a great job of explaining why different eras have different prose styles like the victorians versus other eras. I’ve also read Into the Woods by Thom Yorke and examination of a 5 act story structure. I’ve really enjoyed that because it talks about the 5x story structure which was used by Shakespeare and quite a few others. A lot of playwrights use that. That’s what I did in To Sleep in a Sea of Stars. I used a five act story structure, which is why some readers have felt like it has one beat too many. I did it on purpose to specifically create the feeling that it was almost like a series within one book. It was a longer story than you would normally get with a 3 act structure. A lot of Bollywood films also use the 5 act structure, which is interesting. So I’m I really enjoyed that book.

Also Anatomy of a Story by John Truby. I think the fun thing about Into the Woods is he starts his book by criticising Anatomy of a Story. So there is no one way to write a story but it helps to read all of these books. They have all been enormously helpful and it does help to read about how other people approach that art and craft of writing and storytelling.

AG: Makes sense. I’m Indian and I’ve grown up on Bollywood movies. And is there any Bollywood movie that you’ve enjoyed?

CP: Well, let’s see: DDLJ, Jodha Akbar, Lagaan. I know it’s Tamil, but Bahubali One and Two, Main Hu Na — that’s such a funny film. I’ve seen a lot of Bollywood films. Oh all the Krish films. I mean those are better superhero films than most anything coming out of Hollywood and I love the colours.

I started with Lagaan because it was nominated for the Oscars the year it came out and then after that it was like this cricket match was as epic as any of the fights in Lord of the Rings. I need to see more Bollywood and I am going back to a bunch of the films by Guru Dutt. Boy, those like Pyasa — those are powerful films. If you’re a storyteller, it is helpful to see stories told from different cultures and different parts of the world.

In Western culture, there’s essentially no reason now why two people can’t be together. You’re black you’re white. You can be together. Oh, you’re Jewish. You’re Catholic Oh, you can be together. Oh you’re poor. You’re rich. You can be together. But in Bollywood, well, mommy and daddy don’t approve of this match. Guess what? You’re not getting married. Or you’re different castes or religions and it’s a big deal. It creates such a great conflict for a romance.

Western stories just don’t have that at the moment. We also don’t do romance for men anymore. I’ve watched an enormous amount of Hollywood films. Western films going back to the silent era with classic Hollywood romance movies for men. They used to be: a young man leaves home from the farm and goes to the big city and gets a job. There he meets a nice young woman who’s a sales lady at the store where he’s working. He has to prove himself to her and win her hand and impress her doing something. But it’s from the man’s point of view instead of the woman’s. When was the last romance movie for guys made?

I remember when I showed my wife Bahubali and she was like, oh, it’s a really long film. It’s kind of late in the day. I said let’s just watch a little bit and see what you think. I think that might have actually been the first Bollywood, no, Tamil film that I showed her. We got about 15 minutes in and I look over at her and she’s just locked in. We watched the whole first film. Then she looked at me and said we have to watch the next one. We watch both of them back to back. They are so epic. It’s amazing.

** Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros

*** Kings of the Wyld by Nicholas Eames

Akshay Gajria is a London-based storyteller, writer, and writing coach. He holds an MA in Creative Writing from Birkbeck, University of London and completed his Computer Engineering from NMIMS, Mumbai. He has ghostwritten two books and his writing has appeared in Skulls, The Writing Cooperative, The Written Circle, Bluegraph Press, The Coffeelicious, Your Story Club, Futura Magazine, The Book Mechanic, Poets Unlimited, StoryMaker, Whiplash and more. He usually struggles to finish his sentences… but gets to them eventually.