The Call of Water by Katie Packman

Passing over the Ouse and through the town square, Lana reaches the heavy church door and pulls the iron handle towards her. Not knowing what she is looking for, she meanders through the church – its innards now a vintage store. The altar houses a collection of pottery from the 60s, whereas the nave, pews uprooted, contains furniture and kitchenware so out of date it has reinvented itself. Eclectic as her taste is, the 70s kitsch from Lana’s childhood lacks the style and timelessness of previous eras, so despite this impressive display, she cannot believe anyone will want orange and brown Tupperware in their kitchens again. She continues to browse the used items, even though she never buys anything. Instead, she imagines what her house will look like if she can ever afford any of these cultural leftovers.

From across the room, the plastic phone draws her in; the bold curved shape gleaming despite its age. The yellow cradle holds a black receiver aloft. She walks over to it and admires the circular dial, also rimmed with black, its bold numbers peeking out of each hole. Her fingers reach into the gaps. Solid and real compared to the screen of her smartphone. She remembers the whirr of her mother’s less stylish beige model as the dial returned to its original place. She drags the number seven round with her delicate finger, watching and listening as it recoils. The cord, a tight black spiral, winds around the base of the old-fashioned telephone and disappears under the table.

Lana steps deeper into the back of the store, where the lack of light drops the temperature by a couple of degrees. Angels stare down at her from the vaulted ceiling. The store, always quiet on a Monday lunchtime, is her private refuge. She avoids the weekend crowds, as sharing confined spaces with others makes her uncomfortable and somehow even lonelier. Never mind the fact he banned weekend shopping: Saturdays are for housework and Sundays for rest.

On Mondays, the owner minds his own business at the till, usually shuffling paperwork. He used to smile and offer a polite greeting. However, since she became a regular visitor, he barely looks up before catching her eye and returning to his work. He knows she won’t buy anything. The seclusion of the church makes Lana feel like Aladdin in his cave of wonders. Alone she indulges in fantasy lives. She contemplates the previous owners: imagining lonely widows. Relieved widows. Orphaned children, now adults, but always children when sorting through the remnants of their parent’s life, making unexpected discoveries, just like she had done. Her fingers drift to her mother’s eternity ring, loose on her index finger. Amongst the silence, she creates her own people to populate the displays. She gazes at the matching crockery set, evoking images of a happy family sharing a Christmas dinner; a Formica kitchen table laid for breakfast with the ugly Tupperware conjures up the bustle of children getting ready for school. The noise of families bickering fills her head. A noise she always envied as an only child. She places an elderly relative snoozing in an armchair built to last. She fills elaborate display cabinets, now empty and dusty, with family heirlooms, chipped and faded from the sun.

The stone interior keeps the air cool. A refreshing change after the stifling heat of her office; with no windows or air-conditioning the summers drag by in a fog of sweat and body spray. The breeze picks moisture up off the Ouse and brings it in through the side door to caress her ankles. Its silty smell reaches her nostrils. Her circuit of the church complete, Lana drifts back towards the telephone.

She leans forward, stroking the cradle with her fingertips, contemplating a purchase. It would create a focus in her hallway, a talking point, and a stark contrast to all the technology her husband has at home. Making it both more and less appealing at the same time. She lifts the handset to her ear. She expects the burr of the ring tone, but instead, the silence of the church whispers down the line. A hum reminding her of the shells she held to her ear as a child: the conch with the sound of the tide inside. How its soft sounds soothed her when she felt anxious. This telephone makes her feel the same. Comforted. She imagines it carries the sound of the Ouse inside it, the ripples of water sploshing as they lap the riverbank. Gently, Lana replaces the receiver and lets her eyes admire the chromatic design. Time feels as if it is standing still today. Her fingertips rest on the receiver, and she feels the vibration before she hears it ring.

A moment passes. Lana stares in disbelief at the ringing telephone. The tone shrill, reminiscent of a time when everyone answered the phone, not knowing who the caller would be. It feels strange to pick up a call and not know who will be on the other end of the line. She looks around for the owner. The ring of the bell continues to echo in the empty church. With no clue what else to do but with a desire for the silence of the church to be restored, she picks up the receiver.

‘Hello,’ Lana remembers the formal greeting her mother recited every time she answered the telephone and wonders if she should utter the store’s name as well, but before she can formulate the words in her mouth, a desperate voice reaches down the line.

‘Help. Help me. Please, is there someone there? Help me. I need help.’

Before her lips have chance to part, she hears the droning tone of a lost line and the sloshing of the ebbing river outside. There is nothing but the silence she longs for. Replacing the receiver slowly, Lana wonders what just happened.

The interruption of the call unbalances her. She looks around. Nothing around her explains what she heard. She checks the phone again by holding the receiver to her ear. The hush, hollow sound of the conch shell fills her head. The shop remains empty. Lana relishes the restfulness of this store; the halcyon atmosphere allows her to indulge in her daydreams. Pure escapism. Her husband – her overbearing husband – who began their marriage as caring and protective, soon morphed into a bully who hides behind his marital duties. Lunchtimes are her only freedom from his critical eye.

Here, by herself, she doesn’t have to believe his snide comments. His verbal assaults, so carefully worded that any retort from her would seem petty and trite. He outwits her daily in a lexical war that she can never hope to win. But his daily victories are never enough. She gave up competing long ago and now only looks for respite, however short-lived. Her words dried up.

Lana’s thoughts drift back to the strange call. Who was asking for help? Why did they call this number? The silty smell of the river drifts through the door. Still alone, staring at the telephone, she questions her sanity first. She remembers the goosebumps. Each individual hair on the back of her neck lifting. The shudder that travelled down her spine. The call seemed as real as the telephone in front of her.

Lana sways left, then right. The blood drains from her face. Her husband’s control paralyses her with fear so innate she cannot fight it. She doesn’t trust herself to help. She is trapped. No matter how much she hates her husband, Lana envies his power. His ability to disguise his marriage as a happy one to all who know him. Neighbours in their cul-de-sac call him the ‘nicest man in the village’: always offering them friendly advice or the loan of his latest power tools. They do not seem to mind his constant supervision. Sometimes, in public, he even manages to convince Lana with his elaborate game of charades. His talent for secret looks of menace and harm; his words like swords, each blow delivered smooth and concise, under the guise of innocent conversations. She winces, remembering vice-like grips under the table, pinching on the fleshy strip of her inner thigh, the squeeze of her sandaled toe under the heel of his boot. The whispered insults masquerading as sweet nothings.

When alone, the voice in her head is clear. Get out. Leave. Run away. But her courage always falters when she sees him. Who will believe her when she holds it all inside? She should have shared her pain sooner. Every bruise and every outburst hidden. After their wedding, she let her friends go and threw herself into marital bliss. But the honeymoon period withered, and his capacity for pleasure diminished with it. Nothing pleases him anymore. Not even sex.

‘We’ll have sex when we want children, Lana.’

If her mother were still alive, she would only tell her marriages are tough. They need work, Lana. Not everything is a bed of roses.

How can she ask for help when other women suffer so much worse? Black eyes. Broken bones. Rape. She placates herself with his virtues: he provides for her, they own their own home, they have all the latest gadgets. No virtues ever erase the terror he fills her with. Her complaints like shallow puddles in comparison.

She chose to marry him.

So she keeps quiet.

How can she help this woman if she can’t help herself?

As her lunch hour passes, Lana remains rooted to the spot, she admires the telephone again and the delicate tea set next to it. Trailing her fingers over the counter, she turns to leave the store. As always, purchasing nothing, but this time she takes with her an additional burden: the voice of the mysterious caller echoing in her head. Pleading with her for help.

The next day, the call and its anonymous voice dominate her thoughts. Like a worm, the words ‘help me’ writhe through her ear canal. Weakening her resolve. Lana resists returning to the store the next day: Tuesday means market day, and the store will be too busy. Feeling guilty, she blames her uncharitableness on self-preservation. Trapped within her marriage. Her husband’s criticisms mingle with the voice on the phone.

‘You’re useless. You’re pathetic. Your life is meaningless.’

‘Help me.’

‘You only have me. Without me, you’re nothing.’

His words ricochet around her skull, even when the distance between them extends to miles.

By the third day, she makes a decision. She may not be capable of leaving a loveless marriage and a tyrannical husband, but equally, she cannot resist the draw to help this woman. Would her will ever be her own? As lunchtime approaches, Lana grabs her handbag and leaves the office. Striding with purpose over the bridge, she stops for a moment to watch as the rowers power down the Ouse. The coach calls out from his bicycle on the river bank. The coxswain shouts orders to the rowers.

‘Spin, spin, spin, draw, length.’

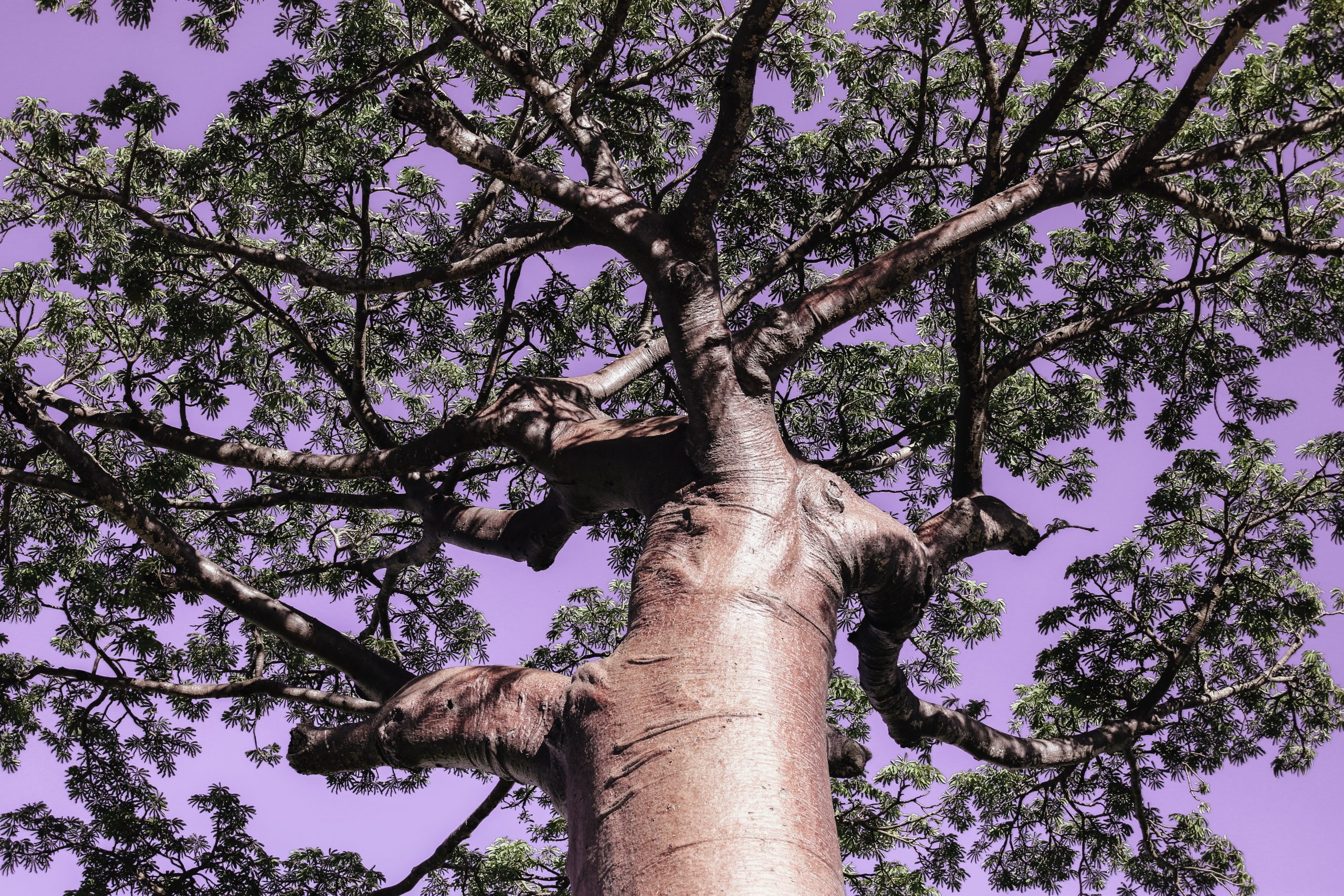

Mesmerised, Lana’s eyes track the oars as they cut through the river’s glassy surface, causing a stir as the ripples slap at the bank. Each stroke of their arms propels the boat forward: forging ahead despite the pull of the current. The rowers disappear under the bridge, and Lana continues towards the church and the treasure trove of vintage homeware, which brings her such comfort.

In the passing days, the owner had moved his collection of goods around and for a split second Lana’s stomach sinks. The telephone has been sold. Frantically she scans each display, dismissing a new collection of kitchenalia she would normally be drawn to, without a second glance. Suddenly, she spots it. Set deeper into the church’s insides, right up at the altar, now displayed under an imposing gothic arch and mounted on a stylish Danish plant stand.

It sits, atop its pedestal, the iconic design resonating around the room. A ray of light breaks through the stained glass and ripples across its surface. She stares at the crucifix above it. A force pulls Lana across the church floor to stand in front of Christ. In front of this telephone.

The arrival of an Indian summer afternoon ensures the store remains deprived of custom, as locals walk the embankment instead. Lana spotted the owner sorting a box of books when she arrived, but now he is nowhere to be seen. The telephone lacks its label; with no description of its design pedigree or any details of its provenance, it seems worthless amongst the rest of the unwanted items. Everything else in the store is stamped with a price, a value – decreed by whom, Lana often wonders. She knows one man’s rubbish is another man’s treasure, but somehow she feels some items must be worth more to the original owner than the meagre sum on the tag. The history, the whys and wheres of a piece, always more interesting to Lana then its design lineage. The cord, now wound up and secured with a disintegrating rubber band, sits next to the phone. A pang of disappointment hits Lana when she sees the telephone is not connected. She realises now that she hoped it would ring again. Lana seeks out the store’s new arrivals; an interesting collection of tin plate advertisements now hang on the church wall.

Taking a deep breath, she exhales loudly. The sigh’s echo magnifying the emptiness of the room.

Once again, just as the silence seems too intense to bear, the phone rings. Lana watches the receiver vibrate with the trill of the bell. It emanates from the telephone right up to the rafters. Lana’s eyes immediately fall on the cord. Laid next to the phone, neatly bound into a tight coil, still trapped by the yellowing rubber band.

Lana breathes deeply and slowly, reaching the count of five before she allows herself to react. Alone, she longs for the owner to make an appearance and answer his ringing phone. Lana tries pinching her arm. The sound stills cuts through the air.

Tentatively, she raises the receiver to her ear.

This time the voice splutters down the line first, ‘Hello.’

‘Help,’ gurgling as if stuck underwater, the voice calls out again.

‘Save me.’

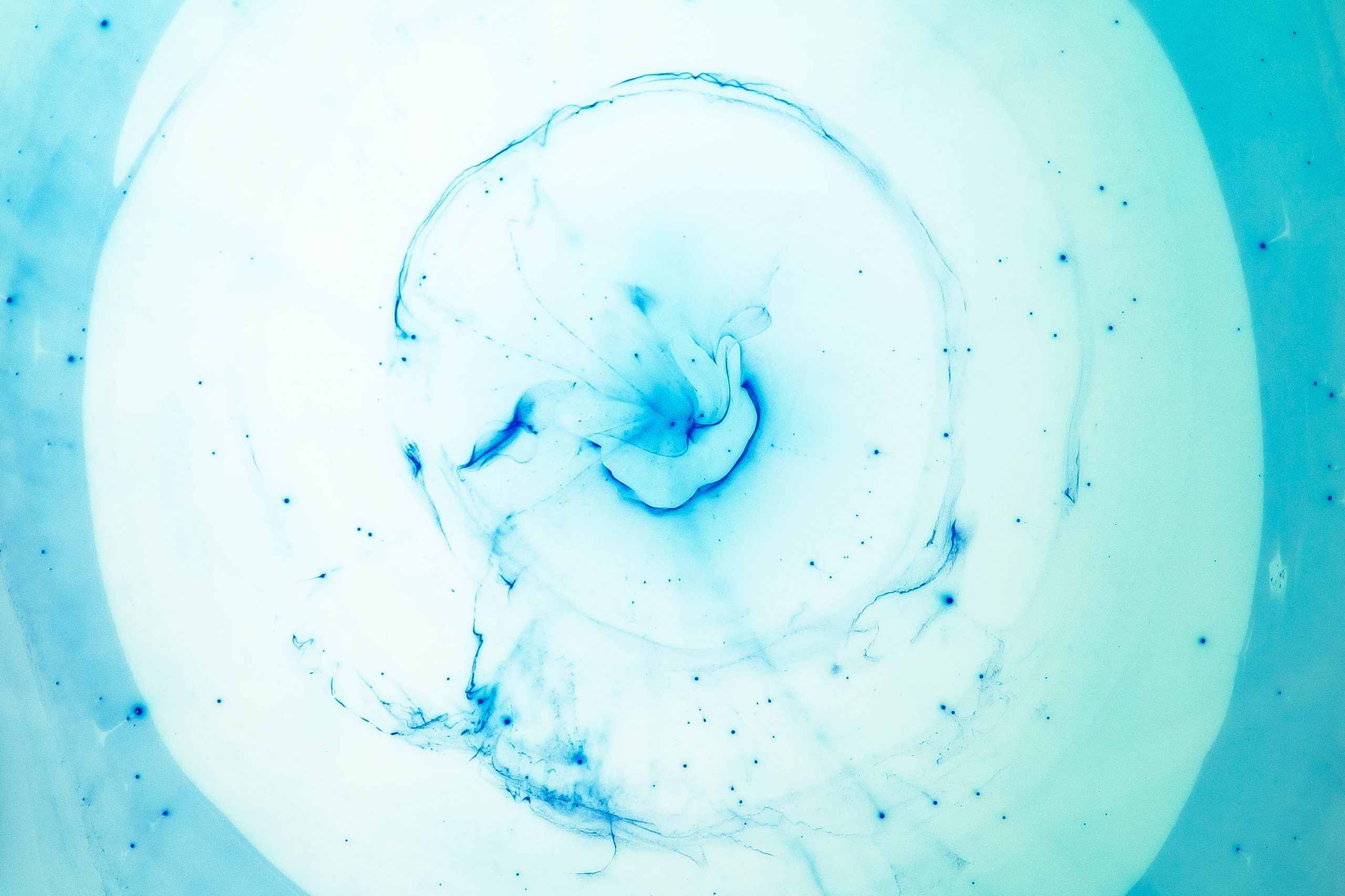

The sound of a river rushes, like rapids tumbling over rocks with the force of an ocean behind them. The cacophonous noise bursts down the telephone and into Lana’s mind.

This time she manages to formulate a response.

‘Where are you?’

Lana grips the receiver so tightly her knuckles push upwards, the bone white under her translucent skin. The desperate voice tries to sound out a word but chokes out a breathless croak. The click of a terminated call follows. Lana finds no comfort in this silence.

Calmly, placing the receiver back in its cradle, she looks around for someone to share her story with. There is no one there. The empty store makes her swallow deeply. Relief swiftly replaces disappointment. Lana knew that she would sound crazy if she tried to tell anyone. Better to keep it a secret.

Heavy footsteps resonate on the flagstone floor. The owner crosses her path. Words sit in Lana’s mouth. Trapped. He nods a silent greeting at his regular customer and wishes that one day she would buy something.

Once back at her desk, Lana browses her screen, considering the impossible phenomenon of the calls. She vows to herself that tomorrow she will buy the telephone. How else can she help the woman on the other end? If she raids her stash of spare change that she keeps in an old bottle hidden at the back of her wardrobe, her rainy day fund, or if she was ever brave enough, a runaway fund, she’ll have enough to buy the telephone.

The following day Lana’s workload does not allow her a break. Her distracted mind, mired by decisions she does not know how to make, slows her progress through her job list.

By the fifth day, Lana can no longer ignore the voice. She breaks for lunch and starts the walk over the bridge. The bipolar weather had abruptly changed the day before. The late blast of sunshine replaced by torrential rain that washed away the last dust of summer. The river swells with its new bounty. Edges of leaves curl and colour. A few scatter her path. The autumn arriving means winter will soon follow, and Lana feels unprepared for the return of long, dark evenings alone with her husband. She pushes the fear of more time at home aside and focuses on the voice. Today she will deal with the voice. She stops on the apex of the bridge to admire the view. There are no rowers, just the sunlight illuminating the surface between each passing cloud. Lana catches sight of her reflection and sees the sadness in her face. Ruined. Resigned.

As she crosses the church’s threshold, the phone rings. Rushing with anticipation, Lana’s shoes clack loudly, announcing her arrival in the vintage store as they reverberate off the ancient flagstones and damp stone walls. Lana no longer cares who watches as her hand flies to the receiver, grabbing the telephone with an urgency she does not understand.

This time the sound of water gushes around her head, its powerful music suppressing the screams of the woman underneath it. Lana hears her anguish. Lana feels her pain.

‘I’m here,’ Lana calls down the receiver.

‘Hold on for a bit longer,’ Lana begs.

Her nails dig deep into the palm of her hand, and the receiver is pressed so hard to her ear, the sound of the swirling water makes her dizzy.

The dampness of the church begins to penetrate Lana’s skin. Cold numbs her fingers and toes first, then creeps up her limbs. The deadline still transmits the sound of rushing water. Lana’s hands drop the telephone and hang limply by her side.

The woman’s screams subside, but a deeper cry now bellows from beyond the water. A muffled shout for help.

Lana’s chest caves in.

Her lungs gasp for air.

Silt clings to her lips.