Interview: JOELLE TAYLOR

“That Really Happened”: An interview with T.S. Eliot Prize Winner Joelle Taylor by Amy Ridler

Joelle Taylor is an award-winning poet and author. She founded SLAMbassadors, the UK national youth poetry slam championships, as well as the international spoken-word project Borderlines. She is a co-curator and host of Out- Spoken Live, the UK’s premier poetry and music club, currently resident at the Southbank Centre. She is the commissioning editor at Out- Spoken press 2020 – 2022. Her poetry collection C+NTO & Othered Poems was published in June 2021 and is the subject of Radio 4 arts documentary Butch. C+NTO, named by The Telegraph, The New Statesman, The White Review & Times Literary Supplement as one of the best poetry books of 2021, won the T.S Eliot prize in January 2022.

*

Joelle is reading from her T.S Eliot prize winning book, C+NTO, at Waterstones Gower street in two hours. We order our drinks at a pub close by and find a quiet corner. As always, her energy is electric…

AR: How does it feel? Has it sunk in yet?

JT: It comes in tides, it’s a bit like the sea. When it was first announced it was just pure shock, followed by elation, and then a little bit more shock. I’ve just been carried away by the waves of various interviews and suddenly there is a real validation, a real joy in being interviewed by well-known media outlets. I was in a bit of a bubble and then I stepped away and, well I’m still in shock. But really enjoying it.

On my way here today to meet you, and every so often since it has been announced, I have a moment where I just stop and think… ‘Yes. I did. That actually happened.’

It’s pure joy, and not just for me. I’m still getting a lot of messages from butch women, and different members of the queer community getting in touch and then, of course, there is the outpouring of love from the spoken word community.

AR: When the news was announced, Twitter was blowing up – my feed was filled with the news. Has the spotlight been a bit overwhelming or are you relishing it?

JT: It was a completely overwhelming experience but in the best possible way. I did panic a bit. I’m used to attention because I am a performer, I am on stage, but I can control that attention. It’s always been very controllable – whoever the audience is in the room and then maybe a smattering of people on social media, but this was crazy! It spooks me that I haven’t been able to respond to everybody. Even good friends of mine. I’ll be walking down the street and suddenly realise – I haven’t replied to them yet!

It was coming at me from every angle. In a sense it would be more tangible if it was 30 years ago and there was a knock on the door and I got 4 boxes of mail, you know? That would have been more tangible – easier to deal with, you could separate it all out and work through it. But I’m not complaining. I did a lot of crying, it was very moving. It has been a magnificent connecting experience.

AR: C+NTO not only brings visibility, but makes it impossible for butch identity, and in a wider context, lesbian history and experience, to be ignored. I remember seeing you perform at your Songs My Enemy Taught Me launch and thinking, I HAVE TO WRITE ABOUT THIS. I got in touch and you very kindly sent me some of your writing, including a section of C+NTO. I did write about it – I named the final chapter of my dissertation ‘Our Whole Lives Are Protests.’

Your work is so important- I imagine there has been an outpouring of support from lesbians around the globe – what’s that like?

JT: It’s been amazing. I knew I was likely to get online abuse – I’m talking about butch women. It’s a historical piece as you know and I thought to myself, I’m writing this book, and I need to be honest. Honest about what it was like, and what it feels like for me, but I wanted to be fairly nebulous in the sense that I want a universal. I want anybody that feels they don’t fit their body to find their place in it. Anybody who has ever had a friendship or a loved a friend whose known that amazing sense of radical community to find their space within my book.

Right from the start, I went out on the road with it. Taking something out there is the antithesis of Twitter – everyone is in the room with you. Every flavour of the LGBT+ community is in the room with you and they are all responding in the same way. All so full of love and joy, even though it is an incredibly depressing piece, but because we don’t get to hear it spoken about; that’s what gives you the sense of joy. It’s giving the voice to something that isn’t spoken about in mainstream culture. It’s been incredibly supportive.

I know what I’m writing about, and I think a real book is not meant to be instructive, it sets the scene, asks a couple of questions, maybe a couple of declamations, and then you do the rest of the work. The responses have been amazing – young butch femme couples are reaching out. The looks on their faces in the audience! I’m an elder, for me it’s really important that this hidden culture, this much maligned culture – because its women – is being elevated, even just a little bit, again and reinvestigated, particularly by younger communities, so that we have the sense of who we all are. I didn’t write the book with any political aim, I wrote it because I was full of grief. I wanted to talk about my friends and I wanted to talk about another grief, which is walking around London and seeing nowhere we used to have. We have 1 bar. People say, ‘there’s a few lesbian bars around’ – there is 1. 1 left. Our bars were our homes, our community centres in a lot of respects. People want these spaces, they want to create those spaces again – including sober spaces.

AR: I have been showing videos of your poems in classrooms around London for a long time, but to be able to talk about your work with students, and tell them that you won the prize – just in time for LGBT+ history month – was amazing.

One of my students said that seeing someone who looks like you, makes her want to take her creative writing more seriously because, ‘people like us are going places.’ She’s sent me 2 short stories since. Visibility is so important. If you could have seen someone who looks like you when you were a teenager, writing and performing, what would that have meant?

JT: That is incredible. It would have shortcut 30 years of journeying, much of which was full of obstacles because of the way I look. It would have meant I could have been myself instead of everyday getting up, trying to look like someone who should be in school in a workshop. That was the biggest panic for me, everyday – that’s why way into my 40s I am still dressing like a punk! I couldn’t find a way of looking that was normal, that was me.

To be able to shortcut that I think is a real power.

It would have meant I had someone to really relate to. To argue with and to not be like, because it’s really important that whilst we respect our elders and what they’ve done, we also find what they didn’t do, and make sure we work on that for the next generation to find fault with. That’s the way we develop and evolve.

I think one of the things I’ve been thinking and talking about – how it used to be. When you went into the pubs, people think it was just like popping into any bar – It wasn’t. It was like going somewhere and being met. Greeted by someone who knew you, as you walked in the room, even if you had never met before. You’re young, and some elder butch would come over and welcome you in, make sure you were sat alright and keep their eye on you, to make sure you’re safe and welcomed – because the welcome is such an important part of a culture that is despised. Suddenly, you’re outside the door and you’re hated, by family, friends, society, and inside the door you are welcomed. This incredible shift, created by 3 inches of wood. Those figures are so important, not just when you are young and new to scene, but all the time. My friend Roman is still that person for me, and for a lot of people. Roman remembers. Roman remembers the old ways and is passing them down.

AR: Who are your go to poets, either poets that have inspired your work OR new poets who you think are shining?

JT: There is some brilliant writing out there. I am hugely inspired by Danez Smith. I was lucky enough to be able to bring Danez over from the states for Outspoken a few years ago, to perform. Don’t Call Us Dead had just come out, it was a really amazing incredible performance- the books incredible, the writing, the passion, the power, the uncompromising nature of all of Danez’s work. I’m part of the spoken word Slam community, and there has been links with Danez for a long time, since they were a kid – they wouldn’t have necessarily known who I was, but I’ve always known who they were, through young slam projects.

What inspires me is the way they balance between spoken word and the page. It’s that balance.

Equally, Sam Sax. Kaddish is a superb performance, the writing is off the hook. I’ve had dinner with Sam Sax and they are an exceptionally lovely human.

Fatima Asghar, If They Should Come For Us is one of the best poems that I use in workshops, its beautiful.

Momtaza Mehri, is going to knock everybody sideways – absolutely stunning writing, her poem Glory Be To The Gang Gang Gang is the best praise poem that’s ever been written. She just does this thing that mixes working class, Muslim and Somalian identities together to create something that’s very new, very fresh. Academic but kind of street. Antony Anaxagorou because he challenges me every day. I can list poets for hours! I’ve just done a list of my 5 LGBT+ poetry collections and it’s actually very difficult to find women who are writing these ground breaking books. Where is Adrienne Rich? Where is Audre Lord? Who are they? Caroline Bird has written some of the most amazing poetry around lesbian subjects, particularly Dive Bar, about Gateways. It’s astonishing. I love it. I’m just very lucky to be inspired by listening to different voices every day and I think there are some really interesting non-binary and trans voices coming through.

AR: Does this recognition feel like an honour to the community, and more specifically to the women who influenced your work? It was already an honour to the community, but has the level of publicity that comes with the prize elevated that?

JT: Absolutely. It feels like a memorial to them. There are far more than I listed in the book. I made a little list on my phone. Obviously I never tell people their real names, but there is a huge long list. It’s not just for the 4 women I talk about – they are amalgamations of people, plus me, I am in every character as well – it’s for people who aren’t explicitly talked about in the book. What I’ve been getting in the feedback is that it feels like that for a lot of people, about their friends.

It’s about grief and loss as much as it’s about butch culture. I think I was trying to get across – and what comes across stronger in the stage play – is the particular grief of how butch women die. I talk about specific instances in the book – violence, drug abuse, alcoholism, suicide, as well as corrective rape and getting battered. There is a real grief in not being able to control our bodies, even after death. It bears reminding younger LGBT+ people that its only very recently that if I suddenly die, my wife can inherit my money. Those things don’t seem to matter when you’re younger, but when you get older, you start thinking: who IS going to look after me? Where am I going to go? And of course, many gay people don’t have that. Some of us lost our families very young, and many still do, in that sense of exile. It has been a memorial, not just for those mentioned but for a lot of butch women, and gay people in general.

AR: If someone had told you, when you first started out, that in 2022 you would win the TS Eliot prize – what would you have said?

JT: Oh man, have I got to wait that long!? (Ha).

No, If someone had told me when I was 22 that I would win this in 2022… It is absolutely mind blowing.

Because I’m from a working-class community, I have two sets of friends. One set is all about poetry and literature, they really get the enormity. The other is all about who we are and where we’re from – and that means when you get something like the Eliot’s or the Booker, or anything like that, whilst your working-class friends are pleased for you, they’re not that involved. They haven’t dreamt of winning the Eliot prize, but they have all been there for me 100%, and I’ve been really really grateful.

AR: What’s next?

JT: I’m doing a lot of touring! I’m off to Australia for a month and it will be the 3rd time I’ve toured across Australia. I’m touring to less places this time, but the size of the events are considerably different. I’m doing Adelaide Writers Week at the beginning, which I’ve done before and it is one of the best festivals I’ve ever been to. From there, we go to Melbourne, for one night only at the wheeler centre, which I’m really excited about because it’s a place I haven’t toured. It is also the home of Butch Is Not a Dirty Word magazine, and the home of a vibrant lesbian culture, so I’m told. Then I finish with 2 events at Sydney Opera house. The tour is threaded together with about eight performances, panels and masterclasses, most of them are remote because it’s difficult to travel across states. Then, when I come back, I’m taking up a poetry fellowship at the University of East Anglia, where I will be terrifying students as much as possible (Ha!). I’m doing a residency for Liverpool University for a week, then off to Finland, Belfast, and Edinburgh International Book Festival.

BUT really, the real work is that I am finishing The Night Alphabet, the book that I started in 2018 AND I’ve been commissioned to write my memoirs.

…and the big big big BIG thing is that C+NTO has been adapted to a 2 hour live musical stage show. We did a section of it in November and we are trying to find a home. I still need to do some work on it, but the aim is that by the end of this year that will be done, ready to tour in 2023. It has the most amazing actors in it, I play Jack Catch. It’s going to have a lot of circus skills in it, and inside vitrines, maybe some DJs from the bell, the door of Gateways, a cigarette burning – So, I’m trying to bring the book alive. I’ve changed the story slightly, to make it clearer, but you’ll have to come and see.

The atmosphere at the Gower street event, reflects the excitement that has been buzzing in the LGBT+ community since the prize was announced. Joelle steps out on stage, impeccably dressed, and the applause is overwhelming. Sitting amongst the people in this audience feels like community. It feels like coming home.

Amy Ridler is a writer and English teacher in East London, where she runs the LGBT+ society. She has written about her experiences as an ‘out’ teacher, most recently in a chapter entitled ‘Miss, are you part of LGBT?’ for Big Gay Adventures in Education, which was published by Routledge in 2021. She has worked with the queer, feminist Live Art Theatre company Carnesky Productions as an associate artist since 2009 and continues to be a member of the company’s advisory board. She is currently an MA Creative Writing student at Birkbeck.

Twitter: @amy_ridler

IMAGE: ROMAN MANFREDI

Review: Voting Day by Clare O’Dea

Craig Smith reviews Voting Day by Clare O’Dea from Fairlight Books

Interview: Valentine Carter

Imagine the female characters of Homer’s epic The Odyssey had voice…

THESE GREAT ATHENIANS, Retold told Passages for Seldom Heard Voices, Valentine Carter’s debut novella gives poetic voice to the mostly forgotten and maligned female characters. A truly unique mix of verse and storytelling, Valentine explores each woman’s tale re-imagining unchallenged and unopposed ideas. And showing there is home in myths for people who exist within and outside gender norms.

Valentine recently completed an MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck, where they are now studying for a PhD. They have had short fiction published by The Fiction Pool, Bandit Fiction, In Yer Ear. And here at The Mechanics’ Institute Review: Issue 15 and Issue 16. I was lucky enough to get a copy of These Great Athenians, the beautifully textured novella, pre-release.

Alice: Hi Valentine, thank you so much. These Great Athenians is entrancing, layered and pertinent. I’ve been familiar with The Odyssey since a child, and I was really moved discovering the women, their voices, their journeys. This re-imagining of an old world begins at how you arrived. Can you give MIR readers insight to how your writing came to this re-telling of old story for the modern world?

Valentine: Ideas tend to arrive from many different directions, but I think the beginning was a lecture I went to with Marina Warner who mentioned, almost as an aside, something about the failure of collective memory in Oedipus as a possible reading and I thought that was really interesting. Somebody recommended that I read Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey because it was by a woman and it was also good. I hadn’t read the poem before because I found the Penguin translation incredibly stuffy and impenetrable, but I knew a lot of the stories. I was really amused by Penelope’s deviousness in unpicking the shroud but also quite surprised at how underwritten the women are given how vibrantly they resonated for me through the stories I had read. I think also around this time I read Pat Barker’s Silence of the Girls and was thinking about retelling the really big myths as an act of protest. All the thoughts joined up and here we are.

In a practical sense, Penelope unpicking the shroud and that so many of the women are weavers was the leaping off point to doing something constructive that involved actually writing instead of sitting about musing. I was interested in repetition in poetry and this being an interesting way to talk about the unpicking of the shroud and how time slows down while you’re waiting, so I started there, with Penelope.

A: The language takes the reader to ancient Greece. A landscape with, for me, some unfamiliar words. Yet it’s an effortless read. Can you tell me more about your research process here? And the merging of old and contemporary language?

V: I’m not a classicist by any stretch of the imagination. I learned about the myths by reading or watching them. I first knew about Jason and the Argonauts because of the film with the Ray Harryhausen stop motion animation, for example. I was talking to someone the other day about how difficult it is not knowing how to pronounce the names of some of the characters because I’ve never heard them out loud. I don’t think any of these things should be a barrier to understanding or enjoying the stories, not for me or anyone else. So, in practical terms, it was a question of getting to the point where if I felt the right word was an ancient Greek one I would do a bit of research and find it. But not in an Eton schoolboy way, I would think about the connection between the word then and where I am putting it. I think this is particularly relevant for the titles in Melantho’s chapter.

I think the choice of language, on a sentence level, goes back to the idea that we look at the past to understand the present. I didn’t want to just transport the characters into the present, I really wanted to try and make that calling back and then projecting forward possible so that when it happens at the end, and we arrive in the absolute present, it seems reasonable to the reader.

I think also it’s important to reclaim the writing as well as the women so that means not making it complicated to decipher as if it’s only for people who’ve had an elite education and speak Ancient Greek. My editor suggested that we include the glossary and I thought that was a good idea because I don’t want the need for prior knowledge to get in the way. I was not an expert in poisonous plants before I wrote Circe’s section. I’m still not, to be honest. Every hedgerow is a potential death trap.

A: Your prose makes each character jump off coloured pages – colour reflecting them and their weight under expected convention. How did colour come into this story?

V: When I wrote the first draft it had a sort of framing mechanism which used a source text that was about categorizing colours. I was interested in the idea that women are labelled in a similar way but then I was more interested in other aspects of the book so as it developed this device became too restrictive. I got rid of it but kept the sections and I think that intention is still felt somehow in the book. It was still in everyone’s thoughts when we got to the design stage as a way of helping the reader navigating the book as it has quite an unusual structure for a novel, or indeed a poetry collection.

A: You’ve made space in this telling. And it was lovely. I couldn’t imagine this story without it. Space is something as a new writer I struggle to embrace. Can you tell me about your experience using space?

V: I think it’s much easier to learn to love space by writing poetry or studying it at least, which is not to say that prose can’t be spacious, just to suggest a shortcut. I think it helps that in poetry the contract between poet and reader is such that the reader expects that they are going to have to work a bit harder and bring something of themselves to the experience. As a result, I think some poets can be braver than some prose writers when it comes to trusting their reader at first. But it is hard and I think you arrive at it by approaching it stealthily along a circuitous route. This is why the novel is in verse mostly, so there’s less heavy lifting in the sentences when staking out the territory.

The idea of space is so important in a lot of different ways. It’s quite metaphorical which is pleasing. There’s the space for the reader to think and to work out how they relate to it and what path they draw from the past to the present and into the future, because it’s different for everyone perhaps There’s my wish to create a space for me, for anyone, to think about these things away from the aggression and noise of the online space or the media. And then there’s the space to discuss and share our thoughts and experience as all different kinds of women. But mostly, of course, there is the desire to create a space for these characters to be heard without having Odysseus or someone else talking over them, or doing something worse, all the time. A safe space.

A: This book is a real treasure that will stand time. Can I ask how long the process took?

V: I tested the Penelope section out on the Spring term class of my second year on the MA and then wrote all the women for my dissertation so that was three years ago now. But then there was a long gap when I started the PhD and I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with it. Then from when I was talking to Nobrow and we decided to work together, I think that took several months from redrafting to this version. It is dramatically different. I also had a chance to absorb everything I had learnt because the MA is a bit helter skelter and, as you know, a lot happens both in terms of writing and being a human! I do write really quickly though when I sit down, I think because I spend so long appearing to sit about doing nothing. This is when all the work happens, while I’m playing Zelda.

A: Anything else for writers hoping to re-tell an old story?

V: I think you need to really clearly know why you are re-telling it and start by re-telling it to yourself. This is what a first draft is anyway perhaps but I think the act of retelling is very much that of the story teller around the camp fire in that there’s an audience and a performance. I think that question of why tell it now is important too although you can answer that as you go along. Maybe the retelling is how you find that answer? On some level I wanted to retell The Odyssey because I didn’t like it that way it was written. Ted Hughes once said that great things are done from a desire to see things done differently and I think that’s true and a useful starting point. Stealing the stories back is also a great place to begin – I feel like a queer reading of Athena is very appealing act of rebellion. Although it’s not a question of stomping all over the source text, I think there does need to be something you love about it, because otherwise what’s the point of stealing it all for yourself?

A: Thank you for you letting me behind the scenes of These Great Athenians. It was an absolute joy to read; empowerment and hope on my bedside table… I would love more please.

Valentine Carter’s THESE GREAT ATHENIANS, Retold Passages for Seldom Heard Voices is published by Nobrow Press. Buy your copy here.

ALICE HAS LIVED AND WORKED WITH AN INVISIBLE DISABILITY FOR 20 YEARS. HER WRITING DRAWS ON THIS EXPERIENCE ALONGSIDE HUMOUR. SHE IS CURRENTLY STUDYING FOR AN MA IN CREATIVE WRITING AT BIRKBECK. SHE LOVES HORSES, DOGS, LOLS AND LIBATIONS. AND SHE HOPES YOU ENJOY READING HER WORK!

Interview: Fran Lock

‘A transformational chase to confound all predators’: An interview with Fran Lock by Matt Bates

In this in-depth interview Fran Lock discusses queer mourning, radical feminism, therianthropy, and why she likes her poems to misbehave.

_

MB: The hyena is an animal which elicits both disgust and distrust, perhaps even a certain queerness. It seems a symbolic choice for your collection. Can you tell us more about your Hyena! poems?

FL: I’m glad you mentioned queerness in relation to Hyena! Across all of the books in which Hyena! appears – and there are now three of them – the hyena is an avatar for particular kinds of emotional experience or thought, experiences that I have come to identify as queer. Hyenas in folklore are persistently figured as fluctuant and threatening; they have outlandish magical properties – their shadow strikes you dumb, there is a stone in their eye that grants the gift of prophesy –, they are harbingers of death and destruction. The hyenas of legend shift between categories of species and sex: neither animal or man, cat or dog, male or female. Queerness is also a mode of being that is imperfectly held within language; that cuts across and partakes of multiple categories of vexed belonging. This otherness is something I connect to my sexuality, but more so to cultural and class identity; to a feeling of being simultaneously both and neither. The experience of queerness is the experience of finding no perfect expression of solidarity, no true home within any single territory or lexical field.

The first Hyena! poem I wrote (‘Wild Talents’) was provoked by a sudden and unsettling experience of loss. It takes its title from a book by Charles Hoy Fort, the well-known researcher into “anomalous phenomena”, and a great collector of therianthropic lore. In Wild Talents Fort writes about the belief that under certain emotional conditions, such as grief or rage, a man might literally turn into a hyena. The news of my friend’s death initiated something in me where, following a sustained period of loss and turbulence, I had reached a state in which animal transformation felt plausible to me; where I felt just feral and disordered enough to turn into a hyena myself. The figure of Hyena! emerged because the accumulative effects of grief were a kind of therianthropy; my own body became strange and dangerous to me, it changed in ways both involuntary and conscious. Grief seems to demand this mutation: normal functioning suspended, caught in arrest and revolt.

I often talk about the Hyena! poems as a work of queer mourning: an exploration of the troubling strangeness grief initiates in us, and a negotiation with the kinds of grief – and grieved for subjects – society does not want to look at. I tend to think of grief as a queering of the real, as a making strange of world and self to self and world. At its most violent edges grief changes how we see and say, what it is possible to think and to know, the words with which and through which we apprehend reality. It is a kind of relational uncannying, it renders communication fraught, it ruptures something at the level of language, requires new words and phrases, new ways of saying.

This frightens people. The hyena’s “laugh” is repeatedly mischaracterised in folklore and contemporary culture alike as demonic, hysterical, or mocking. Throughout my research, I began to relate this to the ways in which the sounds of women’s grief and trauma – and the grief and trauma of queer women in particular – are also misunderstood and shunned. Throughout all the Hyena! poems, there is absolutely a confrontation with this historical disgust and abjection. The hyena has great symbolic weight for me. I feel a powerful identification with her.

MB: There is a passage in the Bible, Isiah 34:14, which reads, ‘The wild beasts of the desert shall meet with the hyenas, and the satyr shall cry to his fellow; the screech owl [Lilith] also shall rest there and find for herself a place of rest.’ I’m struck by how elements of this short piece of scripture are encapsulated within your poems. Religious and mythological misogyny is a concern throughout Hyena!, most apparent in Tiamat in South West One. Can you tell us more?

FL: You are absolutely right, religious misogyny is an animating force across all of the Hyena! poems, but in the later pieces these concerns are at their most furiously present.

Tiamat is the Mesopotamian goddess of chaos and creation, best known from the Babylonian epic, the The Enuma Elish, where she symbolizes the forces of anarchy and destruction that threaten the order established by the Gods. Marduk, who eventually kills Tiamat, is the god-hero who preserves that order. In her battle against Marduk, Tiamat effectively creates her own army by giving birth to monstrous offspring, including three horned snakes, a lion demon and a scorpion-human hybrid. You can probably guess how well that turned out. The foundational myths of patriarchal society are predicated upon the violent subjugation of disobedient women. In the chaoskampf between Tiamat and Marduk, female creative and biological power is exaggerated and distorted, figured in its most negative and repulsive aspects: Tiamat is the unnatural mother of grotesque children; she is full of rage, she ‘spawned monster-serpents, sharp of tooth, and merciless of fang; with poison, instead of blood, she filled their bodies’. The myth functions as both a conquest of female power, and the disgusted refusal of women’s fury.

I worked through the figure of Tiamat for this particular poem, but she might just as easily have been Lilith or Eve: the yoking of dirty animality and womanhood is a relentless motif in Judaeo-Christian scripture. Tiamat might also have been a witch. Where witch belief is alive and kicking – as it is in many parts of the world – rumours of animal transformation still attend accusations of witchcraft; the witch still has her familiars: the bat, the owl, the toad, the hyena, and the witch takes on their most malignant characteristics, she sheds her skin and becomes a beast: filthy, both literally and morally.

In Animal Equality: Language and Liberation (2001) Joan Dunayer writes about the process of dehumanisation, and the inherent speciesism necessary for this process to work: to reduce the human to the level of an animal we must first devalue the animal. The brutalising treatment of animals, then, is not merely cruel, but a necessary precursor to misogyny, to homophobia, to fascism, and to all kinds of human atrocity. As a culture we become accustomed to cruel acts by perpetrating them first against animals; speciesism also creates the language in which it is possible to dehumanise the “other” amongst us. Religion, sadly, has excelled at such language games, and this is a large part of what these later Hyena! poems wrestle with.

MB: You preface Tiamat in South West One with a quote from Mary Daly. In Gyn/Ecology (1978), Daly asserts that ‘Patriarchy is itself the prevailing religion of the entire planet…’ which is both profound and depressingly true. How has radical feminism informed your work?

FL: I am glad you brought up radical feminism. “Radfem” is not a popular subject position at this particular cultural moment, is it? Largely due to frequent distortions from the phoney-baloney culture war. I won’t dwell on that. I will say that I came to radical feminism at a time in my life when I needed a space and a framework through which I could articulate and understand many of my own formative experiences. I also needed a mode of writing and thinking supple and muscular enough to accommodate and channel my rage. It was either that, or be consumed by it, be destroyed by it. Radical feminism created discursive and intellectual space for me; gave me the rhetorical resources to think analytically about my life, and to comprehend that life in the broader context of a global struggle for women’s liberation – which is also inherently anti-racist, anti-colonial, and anti-capitalist.

In terms of the Hyena! poems, I think radical feminism functions in the first instance as kind of embedded permission to write about feelings, thoughts, and experiences that are not considered (still) quite acceptable to vocalise. Whatever else the poems are “about”, they are also – collectively – about inhabiting and negotiating the category of woman. Even as a child I understood that I was inferior for being a girl, but also inferior for not living up to some imagined standard of girlhood. For women, the signifiers of race and class, such as accent and grammar, are intimately linked to perceptions of femininity, sexual availability and moral worth, so as a working-class and culturally “other” woman, you are already evicted from the hallowed precincts of the acceptably feminine the minute you open your mouth. Your de facto status as a non-woman, non-person contributes of course to your exploitation. There’s a nice irony that middle-class white women are continually figured as more vulnerable and fragile than their BAME or working-class sisters, when it is precisely our status as such that render us – on a systemic level – more so. That fiendish intersection of ethnicity, class and gender is the radical feminist through-line in these poems. It’s something that I don’t think either mainstream poetry or politics has ever sufficiently grappled with.

In terms of Hyena!‘s biggest intellectual influences, Mary Daly is tremendously important, and other foundational figures such as Audre Lorde, Andrea Dworkin, and bell hooks. The work is also inspired by and in many places channels more “extreme” or “fringe” figures such as the playwright and queer activist Valerie Solanas, and the artist and occultist Marjorie Cameron, and the black bisexual blues singer, Ma Rainey. The Marxist feminist writer, Silvia Federici is another important figure for Hyena! In her book, Caliban and the Witch, Federici talks about a belief in magic in early European societies as a massive stumbling block to the rationalisation of the work process. A belief in magic functioned as a kind of refusal of work, a form of insubordination and grass-roots resistance. Women’s claim to magical power in particular undermined state authority because it gave the poor and powerless hope that they could manipulate and control the natural environment, and by extension subvert the social order. Magic must be demonised, persecuted out of existence, for the projects of colonialism and capitalism to be realised. This reading of history has been hugely important to me, especially with regards to the suppression of the caoin and related lament traditions in Ireland. People tend to see religion and science – or more broadly the rationalist agenda of the “enlightenment” – as oppositional forces. One of Federici’s significant claims in Caliban and the Witch is that, in the suppression of magic and the persecution of women, their aims were horribly aligned. That grim pincer movement gets a thorough working out through the Hyena! poems.

I think it’s still true today that the white middle class patriarchy has been so effectively naturalised as the absolute model for all human experience that it cannot recognise or permit any other forms of meaning-making, or can only understand them as pathological, backward or otherwise aberrant; the customs and beliefs of the “white, other” are particularly irksome because they disrupt the categories – “liberal”, “progressive”, “rational” – from which white middle-class identity is constituted. Magic is like rage; it is a fly in the ointment. Many kinds of folklore, magical thinking or witch belief crop up throughout the collection. I owe this to my radical feminist foremothers, but also to a rich familial and ancestral culture. Making space for these beliefs, these modes of thought, is a form of creative protest.

MB: The poems often move from present to past seamlessly in a continuum of different voices which yearn for freer movement and strain against feminine structural constraint. Would it be to correct to suggest that you use timelessness as a way of negotiating such restrictions?

FL: Tense is extremely important to me, not just with the Hyena! poems, but throughout my practice in general. I’ll often have poems written years apart that explore a different portion of a speaking subject’s life. For instance, I see the teenage speaker in Last Exit to Luton, which I initially wrote in 2013, the young mother in How I Met Your Father (2014), and the little old lady in Gentleman Caller (2015) as embodying different phases in the life of one woman, one “character”.

Tense, for me, is another kind of metaphor. I’m using it to try and talk about the tangled threads of intergenerational trauma, especially for women, especially for poor and Traveller women, especially in Ireland. I always like to reference something Eleni Sikelianos says about a poem existing outside of time, while being deeply embedded within it, how a poem can pivot between the temporal and the extra-temporal, can hold us in suspension outside the rational flow of time. This is also “trauma time”, the disruption to or breaking of the unifying thread of temporality. Trauma manifests, according to Freud, through its traces, that is, by its aftermath, its effects of repetition and deferral. Trauma loops, stutters, skews, resurfaces. It is part of the same continually repeating and extending present. So in the first instance, I think my movement between different voices, different lexis, and different historical scenes is a way of exposing that continuum of trauma, of violence, in the lives of women. But also yes, absolutely, it also becomes a method of resisting or evading that violence. It is a kind of code, a way the different voices have of talking among themselves across history. Hidden in history, if you like, as opposed to hidden from.

MB: The dressed, layering, or (un)covering of the female body is a persistent theme throughout Hyena!, perhaps most evident in Part II of Three Jane Does (which is astonishingly beautiful, by the way!) and For Those of Us Found in Water, in which you write of ‘the body masquerading | as a mannequin, an angel, | a perfect lily of tv dread.’ Can you tell us more about this as a theme?

FL: Firstly, thank you. Secondly, this cycle of poems is a sequence I have been calling Hyena! in the Dead Girl Industrial Complex, and it grew out of a long consideration of the ways in which art and culture exploit and consume the violent death of women and girls. I’ve read a great deal in recent years about the sensationalising of women’s rape and murder, but that never felt quite right to me, except in the sense that “sensation” is an inoculation against empathy. I think the situation is more complicated – and in many ways worse – than that. On one level culture is absolutely obsessed with the fatally brutalised female victim, but it also has a hard time really looking at her, of acknowledging that body as a person, that body as a citizen, a subject. While culture has the capacity to become enthralled by individual narratives of violent crime, what’s missing is an understanding of the system and the society that produced that violence. Capitalism creates the material conditions under which these women are likely to become victims. And capitalist culture – the attitudes it endorses – creates the ambient social conditions under which men are more likely to become perpetrators. Capitalism is the chief enabler of male violence. It creates an underclass of vulnerable women. Sometimes being the victim of male violence is the only thing that makes those women visible and present within our culture. We contend every day within language and life with so many registers and levels of invisibility that I’m not sure the death of women and girls is sensational entertainment any- more, it isn’t entertaining; it’s banal, it’s beige, it’s background static. We’re used to it. Girls grow up with it, it’s part of their understanding of the universe and of themselves. I think that’s one of the reasons that the poems are so preoccupied with the body, and the ways in which the body is seen or unseen, is hidden or revealed.

That uneasy tightrope walk between disclosure and restraint is something I think poetry does particularly well, so the poems function as small units of lyric resistance to the kinds of coerced visibility demanded of women – even dead ones – by capitalism, and to their simultaneous erasure as citizens and subjects. Simile and metaphor are disguises, costume changes, feints and transformations for my speakers. There’s an old English ballad, ‘The Twa Magicians’ or ‘The Lady and the Blacksmith’ in which a blacksmith threatens to deflower (rape) a lady who vows to keep herself a maiden. The two antagonists begin a transformation chase: the maid becomes a hare, and he catches her as a dog etc. There’s a nauseating version of the ballad by Francis James Child, but in most other renderings the maid escapes. Her magic is greater. I look on the poems a little like that. A transformation chase to confound all predators.

MB: The Hyena! poems forgo capitalization. As a reader, I warmed very much to this egalitarian form and your inclusive voice. What made you take this approach?

FL: I am thinking of having the following Donna Haraway quote – a favourite of mine – tattooed across my back: ‘Grammar is politics by other means.’ It’s true, and it’s true of punctuation too, I think. There’s something about a lack of capitalisation, especially of proper nouns, that feels disruptive to that traditional hierarchical relationship between writer and reader, between the poem’s speaker and their addressee or interlocutor. None of my speakers talk with a capital ‘I’. They’re too unreliable for that; they’re too uncertain of their identity or status, or else they reject the imposition of that identity or status, all those shitty sectional interests, those ready-made categories of belonging. Because the collection is about transformation, there are no stable speaking subjects, no monolithic entities known as ‘I’ or ‘you’. My speakers are a commons, a network, a coven, a brood. They speak with intimacy and urgency. Punctuation is a wall around the poem, it is a kind of status claim, it is a kind of border. I’m not a fan of borders.

I’m also interested in the way that the removal of capitalisation serves to problematize the relationship to time of both the speaker and the poem itself. Throughout the series of poems, I’m using punctuation to preserve and create rhythm, but removing that which consigns the poems to discrete, objective parcels of time. I like the idea of a poem that steps outside of itself, that isn’t quite behaving on the page as a poem should, that cannot be understood exclusively on those terms. I like that you used the word “inclusive”. I think my lack of capitalisation is embracive, a reaching, a crossing.

MB: In his foreword to Carl Abrahamson’s Occulture (2018), Gary Lachman makes the distinction that ‘there is a purposive element behind the idea [of an occulture], a self-consciousness associated with earlier art movements, a need to define itself against the backdrop of the ever-increasing plethora of information, entertainment, and distraction that characterizes our time.’ How conscious are you of the elements of both acknowledgment and resistance in your own poetry?

FL: I love that we’re talking about occulture, because this is something that comes up more than once across the Hyena! cycle, whether in relation to the practice of the caoin in Ireland and elsewhere, in thinking about queerness and bisexuality, or in referencing more broadly practices, languages and cultures that have been forced underground through the Janus-faced violence of exile and assimilation. An occulture is different from a subculture, to my mind, because it cannot come to an accommodation with the dominant culture; it is not suffered to exist as a kind of safety valve for that dominant culture. An occulture is that which is absolutely indigestible to the mainstream, to capitalism, to patriarchy. It will not be compressed into neatly delineated binaries. It is porous and multiple, seething. It scares people, and so it must remain hidden. In hidden places pressure builds and power gathers. By which I mean that the secrecy necessary for survival becomes the occulture’s greatest strength. Just the idea of being hidden or undefined has tremendous weight and power within neo-liberal surveillance culture, which wants us to be visible at all times and at all costs, and parades this very visibility as somehow inherently radical. I don’t buy that, Hyena! doesn’t buy that either.

Thinking about the idea of acknowledgement or resistance in the Hyena! poems, there is certainly an engagement with prior movements, figures, beliefs against capitalism’s endlessly scrolling torrents of content. This is an act of potentially radical return, I think. It is the creation of a temporal glitch, a loop, a skip; it drags the past into the present, refuses or refutes the idea of “progress”, this notion that history is a straight line, an uncomplicated angle of ascent. As a kind of metaphor for this idea: there’s a host of musical subgenres that grew out of the former Soviet Union, usually grouped together under the heading “Gypsy Brass”. These musicians play extremely fast, coruscating brass on instruments that were often literally retrieved from the earth, dropped by retreating military bands. This is the way my poems are acknowledging and holding these prior traditions; this is the way they are carrying the muck and pain of immediate history with them: by making it sing, by mining it, by proving that it isn’t over yet, you can still get a tune out of it.

In terms of queerness, I’m also deeply conscious of the fact the language we have for talking about queerness doesn’t allow us to talk about it as a positive quality; it is constructed as something done to the ordinary; it cannot constitute itself; it can only exist in relation to straightness. This either-or proposition is the hidden historical violence of the word “queer”. If you’re not us, you’re nothing, you’re inhuman, subhuman. This language assumes a stable centre from which we deviate; it implies damage or deformation. This is deeply melancholy for the queer subject; it infuses queer desire with yearning. What we need – want – are impelled toward – is the establishment of a centre of our own. Until we reach it, what is extra in us is made to feel like a lack, a hole, a cavernous pit. I think the poems are trying to establish that centre, to confirm a compassionate mutuality, a commons, if only within imaginative space, if only across history. It isn’t just writing against the shitty heteronormative capitalist patriarchy (although it is also that), it is trying to signal back across time that we are not – have never been – alone.

About Fran Lock:

Dr Fran Lock is the author of numerous chapbooks and nine poetry collections, most recently Hyena! Jackal! Dog! (Pamenar Press, 2021) and the forthcoming Hyena! (Poetry Bus Press, 2021). The Hyena! cycle is concerned with therianthropy – the magical transformation of people into animals – as a metaphor for the embodied effects of sudden and traumatic loss. Through the figure of Hyena! Fran negotiates the multiple fraught intersections of dirty animality, femininity, grief, class and culture, to produce a work of queer mourning, a furious feral lament.

Fran is an Associate Editor at Culture Matters where she recently edited The Cry of the Poor: An anthology of radical writing about poverty (Culture Matters, 2021); she edits the Soul Food column for Communist Review and is a member of the new editorial advisory board for the Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry. Together with Hari Rajaledchumy, Fran recently completed work on Leaving, an English translation of poems by the Sri Lankan Tamil poet Anar, for the Poetry Translation Centre. The final book in the Hyena! cycle, Hyena! in the Dead Girl Industrial Complex is due next year, and her book of hybrid lyric essays, White/ Other, is forthcoming from The 87 Press, also in 2022.

Fran teaches at Poetry School and hides out in Kent with her beloved pit bull, Manny.

Other Works:

Flatrock (Little Episodes, 2011)

The Mystic and the Pig Thief (Salt, 2014)

Muses and Bruises (Culture Matters, 2016)

Dogtooth (Out-Spoken Press, 2017)

Ruses and Fuses (Culture Matters, 2018)

Contains Mild Peril (Out-Spoken Press, 2019)

Raptures and Captures (Culture Matters, 2019)

Hyena! Jackal! Dog! (Pamenar Press, 2021)

Hyena! (forthcoming, Poetry Bus Press, 2021)

Hyena! in the Dead Girl Industrial Complex (forthcoming, 2022)

Poetry collaborations and chapbooks:

Laudanum Chapbook Anthology: Volume Two (Laudanum, 2017,) with Kim Campenello and Abigail Parry.

Co-Incidental 1 (Black Light Engine Room Press, 2018), with Jane Burn, Martin Malone, and p.a. morbid

Triptych (Poetry Bus Pres, 2019), with Fiona Bolger and Korliss Sewer

As editor:

With Jane Burn, Witches, Warriors, and Workers: An anthology of contemporary working women’s writing (Culture Matters, 2020)

The Cry of the Poor: An anthology of radical writing about poverty (Culture Matters, 2021)

As translator:

Assisting Hari Rajaledchumy, Leaving by Anar (Poetry Translation Centre, 2021)

Interview: Imran Mahmood

[NB – There are no spoilers in this review…]

It’s not often that an interview with an author, let alone a crime author, starts with a conversation about Proust and In Search of Lost Time (À la recherche du temps perdu). Mind you, it’s not often that I interview crime writers, and I’m not usually asked to review crime fiction. But this book isn’t really crime fiction, as the publishers would make you believe, but something completely different; original, intriguing and compelling.

I Know What I Saw tells the story of former banker Xander Shute, who has been living on the streets for thirty years. One evening, after an attack by another homeless man, he finds himself hiding in a luxurious Mayfair house where he witnesses the murder of a woman. Confused, he tries to tell the Police what he saw. They don’t believe him, and as the story develops and Xander searches for answers, his memory continually plays tricks on his mind as he confronts his past that he has been hiding from.

Written in the first-person present, I Know What I Saw goes to the heart of what we remember and what we choose to remember. It shows Xander as a flawed, unreliable protagonist, someone who is so lost and confused that he finds it hard to piece things together, apart from memories of his childhood living with his disciplinarian father and competitive, over-achieving brother. It is these memoires, like Proust’s madeleine that are etched into his mind, as he wanders through London’s streets looking for answers to what he saw, or didn’t see.

Reading the book I was startled by Mahmood’s ability to make the reader doubt their own view of what is going on. That might be the point of great crime writing, I suppose; the writer’s capacity to create doubt and uncertainty at every twist and turn. But reading I Know What I Saw, I began to doubt my own thoughts about what was actually happening, just as Xander Shute’s memory also plays tricks with his mind. I wanted to know what was really going on and managed to catch Mahmood one Friday lunchtime over zoom.

I started by asking, why Proust?

Imran: When I was 15 or 16, I met a homeless man in my local library who asked me if I was interested in some of his French books. I was into reading French literature at the time and he gave me a copy of In Search of Lost Time. I thought and still think it is the greatest piece of literature ever produced because it deals with the idea of memory so beautifully. It questions the idea of what we mean by memory and identity, and how, the older you get, the more you are changed by what you remember, and this is exactly what happens to Xander Shute. He is constantly taken back to memories of his previous life, but because he’s been on the streets for so long, everything is a blur. Proust also makes us think about what it’s like to stand on the edge of a precipice looking into the abyss, and that we sometimes need to go to that edge to fully understand what we are suffering. That’s why I included the quote ‘we are healed of a suffering only by experiencing it to the full’ at the start of the book. Proust was my way into Xander, who was previously protected by privilege and education but isn’t anymore, and life has now caught up with him.

Miki: Is this a book about the self?

I: The crime is just a vehicle. I’m keen to use it to explore other themes and in fact, I’m not massively interested in the crime itself. I’m a lot more interested in what it tells us about the human condition. Here you have a man, Xander, who was from a perfect background, but I wanted to show what it must have felt like for him living and being trapped in this new impossible life. This life on the streets, moving from place to place, living hand to mouth. That’s why I wrote it in the first-person present. I wanted to give the reader a sense of claustrophobia. I want readers to be right there, with him, in that moment.

M: It seems to me that your work inspires your writing?

I: Being a Barrister is relentless and the subject matters I work with can be pretty dark. What has amazed me though throughout my career is that people are incredibly tenacious. I see it every day. Sometimes I wonder how certain people can go on, but they do, which is a testament to the human condition. People, like those that I represent have an innate desire to keep on going, even when everything else aaroundthem falls apart. I find it remarkable, and I wanted Xander to have the same qualities of resilience.

Also, in my experience, criminals always deny responsibility. I see it all the time. The fact that they have denied a crime makes me think that there are trying to re-write who they are as people. That is fascinating to me, and in some ways, it is what Xander is doing; trying to re-invent himself, make out that things didn’t happen when in fact they might have done.

M: Xander was on the streets for 30 years. This to me seemed like a long time, but we see very little about that period of time. Was that deliberate?

I: The first title I had for the book was ‘Exposure’ because I wanted to show that someone is likely to die in three days if they have no shelter. The publishers weren’t keen on that title, but I was more interested in what being on the streets for a long period does to someone. What is left of that disfigured, slightly twisted person? What has Xander experienced that has influenced how he thinks and what he does? I didn’t want to look at his daily life, as the risk is that you then comment about the phenomenon of homelessness and every experience is different. So, I kept coming back to this idea of memory and identity. Who was this person before they became homeless and who were they now?

M: Do you plan your books carefully before you start writing?

I: Not at all. I remember Lee Child saying that he never plots anything and just likes to find out where things will go. That’s how I like to write. I plot late at night when I’m in bed and let things visualise in my mind and then I’ll maybe write a line or 5-6 words per chapter, so I know what I’m doing. So there’s not much structural planning. Some people find it easier to plot, but maybe I’m like Xander, I like things to percolate. But it suits me as I have a very unstructured writing routine which means I end up writing in cafes, courtrooms, while waiting for verdicts, on trains, buses or when everyone is asleep at home.

Mahmood is the latest in a long but distinguished line of high-profile crime writers from British-Asian backgrounds, that includes Amer Anwar, Abir Mukherjee, Alex Caan and others. Throughout our conversation I was struck by his thoughts, not only about writing and how his ideas evolve, but also about the publishing industry that he feels still has some way to go before it truly represents writers from underrepresented backgrounds.

I Know What I Saw is a captivating, relentless read, but also a thoughtful and stunning look at how memory and identity can fade and change over time.

Buy a copy of the book here

Miki Lentin took up writing while travelling the world with his family, and was a finalist in the 2020 Irish Writer’s Centre Novel Fair for his novel Winter Sun. He has also been published by Leicester Writes, Fish Publishing (second prize Short Memoir), Litro, Village Raw Magazine and writes book reviews for MIR Online. He dreams of one day running a café again. He is represented by Cathryn Summerhayes @taffyagent. @mikilentin

Interview: Iphgenia Baal

Iphgenia Baal is a London writer. She’s a former journalist and a self-publicist of two zines. Her first book, The Hardy Tree, was published in 2011 by Trolley Books, who also published Gentle Art in 2012. Death and Facebook was published in 2018 by We Heard You Like Books. Her most recent work is Man Hating Psycho, published last month by Influx Press.

I’ve read her latest book twice – it’s utterly absorbing and hilarious in its interrogation of the disconnect between our identities and real-life-selves, exposing the inherent duplicity of online communication and how this plays us into the social order. Iphgenia has a unique prose style that has been described as visionary, a ‘marrying of politics and ass’, likened to writers as varied as James Joyce, Manuel Puig and Dodie Bellamy.

Alice: I loved reading Man Hating Psycho! I love the way it draws out social insanity in a very funny voice. What is your synopsis of Man Hating Psycho? Why did you write it?

Iphgenia: I’m not sure I’m qualified to give you a synopsis of the book. I’m never sure what I’ve written until years later, so you’ll just have to go with the blurb. As for why I wrote it, I wrote it because I write.

A: The opening text ‘Change☺’ is a What’s App group conversation. The Usernames gave great leverage to the characters in conversation, like ‘EnglishTwerkingClass’. I’m guessing there’s a mixture of fiction and non-fiction here. How did you develop this voice using social media?

I: I didn’t really develop anything. This story was delivered to my phone near-word for word to how it appears in the book. I cut bits and bobs and jiggled a few sentences around but other than that the only authorial decision I made was to copy it out and publish it. The names came about through necessity because it is (apparently) morally and legally questionable to publish people’s real names and phone numbers alongside real messages they sent, so I anonymised the names in a way that amused me.

A: Brilliant! I really felt I was in the narrator’s head throughout, following their train of thought, feeling their dismay, conjuring questions onto the tip of my tongue, then bam, the narrator asks them. Genius. And it never felt like an exhausting rant, it was funny. Can you give insight to how you managed this – to write cross without losing the reader?

I: I write how I write, which is also how I talk. Some people get it, like it, agree with it, are amused by it… like you seem to be, while others are bored or offended by it and go around telling people I am “evil”. I guess what I’m saying is that it’s tough to give any insight of note into a mode of thinking that is so intrinsic to me. But I think it’s also true that people getting cross are almost always funny…

A: Each text heading really helped contextualise content, like Vodafone.co.uk/help. It allowed me to get an overview of the work’s voice as a whole. What came first – the text or the heading?

I: Titles only ever come to me after I’ve written something, never before. Usually, I know something is finished because a title occurs to me.

A: You really make use of different fonts and white space. Can you talk about your editing process here?

I: Man Hating Psycho has been the most hand-off experience I’ve had of publishing. Usually, I write in InDesign and typeset as I go. I suppose a little of that crept into this book at my insistence. Personally, I wouldn’t like a lot more. But yeah, I often use text design as a way to edit content, albeit in a haphazard way. I think it comes from my time writing for magazines combined with an aversion to Microsoft Word.

A: You’ve achieved a lot of publications for a young writer – any top tips for Birkbeck writers?

I: Tbh, I don’t know why anyone would want to take tips from me. I might have written a few things that have been published but I’ve made a humiliating amount of money out of doing it and in the process opened myself up to attacks from countless loathsome buffoons. The end result is that I’ve written myself into a corner where I am basically unemployable, so sorry, no motivational titbits.

Thank you for this insight into your process, Iphgenia. I can’t recommend enough that writers, well, everyone reads Man Hating Psycho. The book is truly visionary in its form with an honest, critical voice that the world would do a lot better with more of.

Buy a copy of the book here

Alice has lived and worked with an invisible disability for 20 years. Her writing draws on this experience alongside humour. She is currently studying for an MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck. She loves horses, dogs, lols and libations. And she hopes you enjoy reading her work!

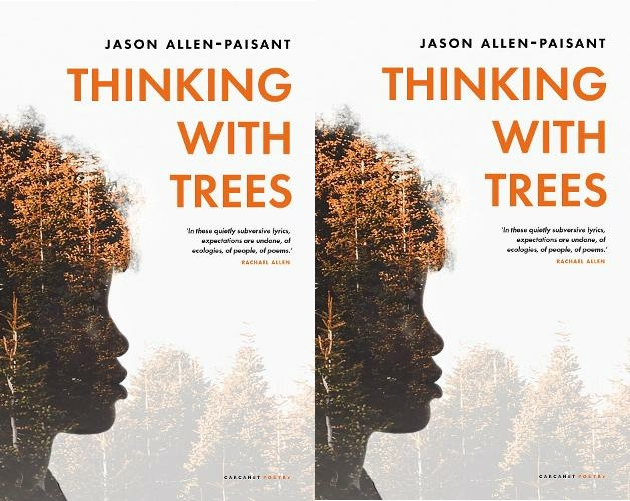

Review: Thinking With Trees by Jason Allen-Paisant

Our Poetry Editor, Lawrence Illsley reviews Thinking With Trees by Jason Allen-Paisant from Carcanet Press

10 Things…with Tom Benjamin

Crime author Tom Benjamin, whose second Bologna-set novel, The Hunting Season, is due out this May, answers our questions.

Review: Dreaming in Quantum by Lynda Clark

Miki Lentin reviews Dreaming in Quantum by Lynda Clark